Chapter

4

Values

and

Related

Matters[1]

All

experience hath shown, that mankind are more

disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right

themselves by

abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.

The

Declaration of

Independence

Now that we have

looked at our political animal both as a

unit and as part of the group, we will examine the elements by which a

group

and its members identify themselves. We are setting out to answer the

question

posed in our last chapter: What is a norm? But before dealing with

norms, we

have to study those elements which provide bases for them. Norms are

related to

values, and values are elemental to group life and political

organization. In

this and subsequent chapters we will deal with values and the matters

intertwined with them. Even their occasional segregations emphasize

their

relationships. If we divide this chapter and those that follow into

different

sections we do not intend to compartmentalize the topics, but simply to

ventilate the study. Each section is titled according to the nucleus of

its

topic, although the areas shade and fade into each other.

I.

Interests

Discussing man and his

groups, we found reasons for his

social behavior. For example, man is driven to provide for his basic

physiological, psychological and sociological needs. When he is hungry

he needs

to eat, when he is tired he needs rest, when he is confined he needs

freedom,

and when he is bondless he needs attachment. All along he has

"needs," which are flexible, retractable and expandable. The yogi of

India can live on an almond a day, while the Western man reaches for

the moon.

Within this span some needs may seem more justifiable than others.

Caught in a

blizzard, a man needs shelter lest he not survive. That need is

imperative, while

the desire of the owner of a comfortable suburban house to upgrade his

dwelling

into a mansion may be considered dispensable. You may notice the word

"need" in one case and "desire" in the other. Although the

two terms are used interchangeably, we may establish, on the basis of

their

connotation, a spectrum ranging from necessities to frivolities. This

semantic

acrobatic will reveal a distinction between the insufficiency of a need

and the

relatively mire comfortable position from which a desire is formulated.

In the

first, the entity in search of its needs may be desperate to acquire

them, yet

handicapped in obtaining them because of their very absence. In the

second,

comparatively abundant means may make the desirable end more

accessible. In the

latter situation, accessibility may relax the drive toward procurement

of the

goal; it may create a tendency to conserve the available means and slow

down

the move toward the goal or it may augment the desirous appetite. In

political

terms, these situations may be illustrated on one hand by the

unfavorable yet

militant position of a disinherited group, class or nation, and on the

other

hand by the powerful position yet conservative or rapacious attitude of

the

propertied.

There is, of course,

no clear dichotomy between need and

desire, and one term turns into the other depending on social context.

Our

example of the man who desires to replace his comfortable suburban home

with a

mansion illustrates the point. Many people may consider him in need.

If, for

example, he has been promoted to the presidency of an important firm,

he may

have to reside in a mansion to fulfill the social obligations attached

to his

position. As it is in the interest of the man caught in a blizzard to

find

shelter, so is it in the interest of our executive and his firm to

acquire a

mansion. These interests provide

functional spheres making life and social life possible. Interests

interpret,

convert and qualify individual needs in social terms. The chief of the

tribe,

the king, the president, the commissar, or the tycoon is treated

according to

the customs and expectations of his position in his group context. The

group

discriminates among its members and establishes gradations of

expectations on

the basis of differentiation and identification. When corresponding to

the

group's fermentations and dynamics, these gradations blend into the

acceptable

social pattern. When we talk about "self-interest" or "national

interest," we are referring to functional spheres believed expedient

for

survival. I was tempted to say "well-being" instead of

"survival," for it is a question not of mere existence, but of its

quality. In Aristotelian terms, Polis

did not come about only for the sake of life, but for the sake of the good life.[2] The concept of good; of course, is in itself

relative; what is good depends on who is formulating it where and when.

But man

claims the faculty of choice, and that implies a scale of preferences.

Although we have

elaborated no hierarchy of preferences,

an order of importance may be inferred, with the immediate needs for

survival,

such as food or shelter, preceding others. The proposition is obviously

elementary. We noticed in earlier chapters that man, like some other

animals,

may renounce his food or his rest in the face of danger. In fact, the

history

of mankind is filled with instances, like-that of the Japanese

Kamikaze, where

men have thrown their vary lives onto scales where self-conservation

did not

weigh the heavier. The loci of security and conservation are at times

displaced

from individual security to preservation of the group, nation, empire,

fatherland, principles, religion or whatever the cause of the

sacrifice. In the

words of Tillich:

Man,

like every living being, is

concerned about many things, above all about those which condition his

very

existence, such as food and shelter. But man, in contrast to other

living

beings, has spiritual concerns-cognitive, aesthetic, social, political.

Some of

them are urgent, often extremely urgent, and each of them as well as

the vital

concerns can claim ultimacy for a human life or the life of a social

group. If

it claims ultimacy it demands the total surrender of him who accepts

this

claim, and it promises total fulfillment even if all other claims have

to be

subjected to it or rejected in its name. If a national group makes the

life and

growth of the nation its ultimate concern, it demands that all other

concerns,

economic well-being health and life, family, aesthetic and cognitive

truth,

justice and humanity, be sacrificed.[3]

Faced with the choice,

man may prefer to die rather than

renounce his country, creed or belief.

The situation is, of course, unlikely. Man is not usually faced

with

such extreme choices, and when faced with them many prefer to live. But

as long

as the ultimate is not present, many will pretend to believe in

sacrifices they

re-ally would not be prepared to make. However, man is

faced with choices, and in making them he simultaneously

conforms with and helps establish a scale of preferences in which his

very being,

although indeed essential, may not always occupy first place.

If so, then is it that

life and what is good for it are

not the key to man’s preferential scale? We may start to answer the

question by

trying to detect differences in the nature of the situations we have so

far

illustrated. Recalling the affectional-functional model in the last

chapter,

with its extremes of emotional and state-of-nature or mechanical

rationales, we

may notice that what was described as the interest

of the newly elected executive to upgrade his domicile could, in the

appropriate group context, correspond to certain functional dimensions

of

social relations.

On the other hand, it

would be difficult to explain the

functionality of an individual’s or a group’s sacrifice of its

well-being and

even its very existence to defend an ideal. The term “interest” does

not seem

to justify fully the Kamikaze’s behavior: hitting a battleship in a

live bomb

is hardly good for his health. The Manichean Colonies of the

Mediterranean

Basin in the seventh century who refused to renounce their belief were

wiped

out by the Christians, who themselves a few centuries earlier had

braved the

teeth of the lions. Such behavior does not seem materially and

functionally

motivated, but nonrational and affectional. Yet, although abstract, it

overlaps

and competes with the concrete and material phenomena we have termed

interests.

In the scale of preferences, it arises from values

as distinct from “valuables.” When the believer donates his fortune to

his

church, he parts with his valuables for his values. Without attempting

a

watertight compartmentation, we may reasonably propose that while

interests are

based more on functional-rational considerations, values appear to

pertain to

the affectional, non-material dimensions of human behavior. But the

distinction

should be applied with caution, as interests and values merge and

generate and

justify each other.[4]

II.

Interest-Value

Insularity

We can distinguish

interests from values by their degree

of finitude. An interest, such as the need for shelter in a blizzard or

a

bigger mansion for the executive, can be identified, formulated,

strived for,

attained and finally consummated. Once a shelter is found or a bigger

mansion

procured, the end is reached. While other similar interests may arise

in time

for the same people, they will all be separately definable in

means-ends terms.

But values like love, patriotism and piety are not attainable once and

for all.

The Kamikaze’s ultimate goal was not to be blown to pieces on the

impact of his

bomb with the battleship, nor did the Buddhist monk burn himself in

Saigon

during the Vietnam War for the pleasure of seeing flames flare about

him. The

goal is beyond the act and, because of the very act, beyond the actors.

Values

that imply finite ends eventually fall into the functional category and

are

therefore closer to interests. A value, such as honesty, must

continuously be

affirmed. You cannot make a balance sheet of your honesty and say, “I

have

attained it,” and from then on become fraudulent. An act of faith does

not

absolve the actor of his faith, but merely manifests the belief that

lies

beyond and that continues even after the act is over. A lover cannot

fold his

arms after a gesture of affection and wait for reciprocity from his

partner. If

he does, he is not loving but doing business. In contrast to

functionally

definable interests, values lie in the affectional sphere. They are

values

because they can only be approximated functionally. If they were

attained, if

they were consummated, they would cease to be values. In the words of

Sartre,

“Value is always and everywhere the beyond of all surpassings.”[5] Man’s ultimate effort in the sphere of his

value is to be consumed towards its attainment, as were the Christians

facing the

lions in. Rome, the Buddhist monks in Saigon or the Kamikazes.[6] Different

natures and dimensions of

interest-value relationships can fit our model. For example, speaking

of

commercial profit as an interest, fair play and honesty as a value, and

wealth as

a goal, or likewise of defense, patriotism and glory, we may visualize

the

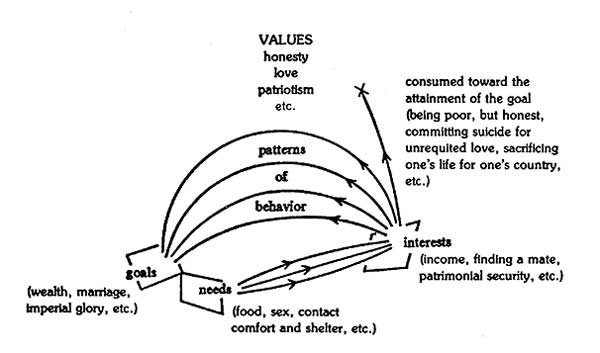

model as presented in Fig. 4.01.

Fig.

4.01

Man’s behavior, then,

is motivated by a pattern of

interacting and intermingling functional material interests and

affectional transcendental

values. Some interests are more directly goal-oriented and value-free,

while

others, in an increasingly transcending scale, are polarized and

value-laden.

There are those who go after wealth, and there are those who go after

wealth

honestly. Some go for power ruthlessly; some are tempered in their

drive by

their fear of God.

As observed earlier,

the gradation from functionally

goal-oriented interests to transcendental values does not necessarily

parallel

the gradation from man’s physiological needs for survival to his

metaphysical

sublimations. Those very goal-directed physiological needs may

themselves be

conditioned by values. Between the appeal to a prostitute for

satisfaction of

the sex drive, a functional extreme, and the romantic love which may

culminate

in sacrifice, there is a wide spectrum of interest-value combinations

which

influence and regulate man’s sexual behavior and which explain, for

example,

the different institutions of marriage. Not only are the interest-value

patterns not identical for different individuals, but they may be

different for

the same individual under different circumstances.[7]

As in our above example, the same man may both seek the services of a

prostitute and fall in love.

In the preceding

chapters we saw that the group as the

unit of identification needed to set a pattern of behavior for its

members in

order to secure its cohesion. The togetherness of the group under given conditions already presupposes a

group pattern of behavior. But both that pattern and the togetherness

may be

caused by the given conditions which may be external to the group. A

shipwreck

may create a group, but the group may not be long-lasting. For the

group to

secure its continuity in spite of the given external conditions (which

may not always

be conducive to its cohesion but detrimental to it) and not because of

them,

the pattern of social behavior among its members should be ingrained in

them.

The group should be more than an aggregate of heterogeneous people

temporarily

brought together by some external factor, and it should be able to

resist

disintegration in the face of external factors tantalizing its members.

In

discussing groupness in the last chapter, we noticed that communication

and

communion brought about understanding and a sense of belonging. But

what was

being communicated, and what was that communion? We saved this question

for our

present discussion. The survival of the group, the security of its

existence

and its interests in the material and functional sense depend on the

conviction

of its members as to the validity of the group itself. This validity

must be

more than the sum total of private material and functional interests of

the

group’s components, for otherwise conflicting interests will

disintegrate the

group. Without such a transcendent validity, there would be no sense in

risking

one’s life, for example, to be a patriotic soldier on the front.

In the process of

communication and communion, then, more

is passed along than the simple rudiments of how to procure material

satisfaction. The pattern of behavior is enveloped in a sense of

“oughtness,”

making conflicting interests reconcilable and giving the individual a

sense of

values. In the words of Perry:

The

quality of moral goodness,

like the quality of goodness in the fundamental sense, lies not in the

nature

of any class of objects, but in any object or activity whatsoever, in

so far as

this provides a fulfilment of interest or desire. In the case of moral

goodness

this fulfilment must embrace a group of interests in which each is

limited by

the others. Its value lies not only in fulfilment, but also in

adjustment and

harmony. And this value is independent of the special subject-matter of

the

interests.[8]

To create this sense

of values, the group, through

socialization, appeals to affectional ingredients of human nature. We

have

mentioned some of these (such as paternal love, faith and patriotism)

as

transcendental feelings---values—corresponding to functional

institutions (such

as heritage, church and state) which serve material interests. Paternal

love

provides heritage, faith maintains the church, and patriotism secures

the

state.[9]

The group appeals to

man’s nonrational and affectional

inclinations to reinforce and coordinate the interests which are

functional

according to the group rationale, but not necessarily so for the

individual

members. When a man is hungry, he wants to eat; indeed, he must eat in

order to

survive. But if he belongs to a primeval superstitious group, and the

only food

available is the totem animal, and he eats it, he may have convulsions

and die

a voodoo death.[10] In this extreme example the organism

responds to the supernatural value more intensely than to the material

interest, and the value is transformed into an internal norm, carrying

its own

sanction and having psychosomatic consequences. The group’s values

stimulate

the group member, are processed by his organism and condition his

response. The

more the value is straightforward and recognizable as a value and its

impact

regulated and controlled, the less confused the organism will be. The

value’s

efficacy depends on how well the organism has been conditioned to give

the

desired response. The voodoo death is the ultimate, uncommon extreme of

such

conditioning, but it helps us demonstrate rather dramatically the vast

gap that

can exist between values and interests. The taboo on the sacred food

emphasizes

the value that safeguards the group’s structure.

But groups are not

amorphous and, in the last analysis,

their interests and structures should reflect the interests of their

members:

If certain values instilled in group members can be detrimental to

their

interest in terms of survival and security, then they must correspond

to some

other drives of the individual members. If order and justice are

prerequisites

for the group’s continuity, it is because of man’s inner need for

predictability. If for cohesiveness the group fosters a sense of

identity and

communion among its members, it is because of man’s psychological need

for

contact comfort and belonging. And if supernatural belief can bring

about a

voodoo death, it is because man has a drive to search and fear the

unknown.

Thus, despite the gap between them, both values and interests are part

of man’s

reality, of his basic needs and drives.

If man’s drives

engender both his values and interests,

then their common origin may imply an organic relationship. What is the

nature

of that relationship?

III.

Interest-Orienting

Properties of Values

Man’s drives and his

search for their satisfaction are generated

by his consciousness of lacks, whether of food, attachment or eternity.

As we

saw earlier, an interest is the formulation of a need and a move

towards

filling the lacuna. But if the move is haphazard, different interests

may – and in

a social context are bound to –

conflict, jeopardizing the social pattern conducive to satisfying the

drives.

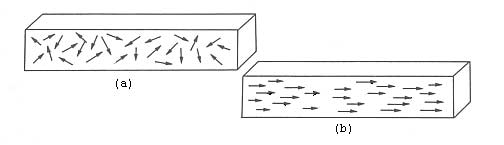

The passage from interests to goals therefore needs some sort of

orientation,

like the molecular magnets in a steel bar which are random when

unmagnetized, but

which are oriented parallel from one pole to another after

magnetization.

Fig. 4.02

Values provide the

field for this orientation of

interests. But as molecular magnets are the same before and after

magnetization, except for their direction in the magnetic field, so

interests

are the same before and after

orientation, except

that some have been sublimated by

values. What we said earlier about the appeal to man’s nonrational

affectional

dimensions to direct the rational and functional should be completed by

the

statement that the appeal is not the point of departure of a

relationship

between two properties other-wise foreign to each other. There is no

such

abstract, independent value as patriotism and another totally separate

entity

as a fatherland; rather, the two are components of an interest-value

constellation which gives meaning to man’s territorial imperative. The

organic

relationship between the affectional and its corresponding

functional—the value

that orients the interest—is causal. Interests and values grow on and

into each

other. We are thus closing the gap between values and interests, but

not to the

extent that pure interest theories do. Both interests and values, as we

have

discussed, emanate from man’s drives and have a circular, organic and

causal

relationship with man’s needs, goals and expectations. Yet they are not

totally

identical. To say that they are, is like saying that the beams produced

by the

flashlight are the same as those produced by the laser because both are

propagations

of light by photons. Such an equation ignores the proportionality of

their

energy and frequency which distinguishes their penetrative potentials.

Transferring our simple metaphor, we may say that values are the

conversion of

interests beyond apparent recognition. Like the laser and the

flashlight,

values and interests are similar up to a certain frequency, intensity

and

concentration, but beyond they reveal different impacts and

consequences.

Liking and wanting become loving—the extrapolation of the ego. The

interest in

security and survival becomes patriotic sacrifice.

Drawing further from

our laser analogy, when man’s

behavior is strictly controlled and directed with intensity within a

field of

values, he is capable of deeds and behavior otherwise beyond the common

realm

of human achievement. We have already referred to some such

extremes—the

sacrifice of the believer, and the primeval man’s voodoo reaction. Like

the

laser, in the process of orientation and intensification, values narrow

their

field and isolate the subject from his surroundings. But we should be

careful

not to follow our analogy with physical phenomena too far because,

unlike the

laser, the consequences of valuational rigidity may, for example, turn

faith

into fanaticism and fanaticism into superstition, thus reducing the

efficacy

and penetration of the values and increasing the group’s vulnerability.

Our

present discussion will gain plasticity if we keep in mind that values

are the

cohesive field for a group. They are the integrative factor in a

homogeneous

group and help orient the members of a heterogeneous group toward

integration.

The results for political organization are obvious.

IV.

Interest-Justifying

Properties of Values

If there is need for a

value field to regulate the passage

from drives to satisfactions, then, in the absence of such a field,

different

interests are likely to clash. The Hobbesian state of nature would

tremendously

reduce the chances for drives to receive satisfaction. In other words,

without

a field of values the chances of filling the lacuna would be scarce,

whether

the basic material for fulfillment is abundant or not. This idea of

lacuna and

scarcity lies deep in the phenomenology of value. It is said that the

creature

most unconscious of water is the fish in the water. The human body

lacks air at

each exhalation, but man is not constantly conscious of air unless it

becomes

polluted or scarce. Maybe we should emphasize here that the concept of

a lack

does not necessarily refer to an absence, but rather to the

consciousness that

absence is possible. The more one is conscious of the irreplaceability

of the

beloved, the more one clings to the beloved. Without that

consciousness, one

takes the beloved for granted. It is not, therefore, so much the

intrinsic abundance

or scarcity of a supply, but rather man’s subjective want and his

consciousness

of that want that provide grounds for the formulation of interests,

elaboration

of their orderly orientation and their sublimation into values. Man’s

subjective perception of a want, independent of the abundance or

scarcity of

its supply, implies that a lacuna can be produced, displaced, magnified

or

reduced by the intervention of values.

As before, we use the

concept of lack and scarcity

universally; i.e., it may refer to a physiological lack, such as water

or food,

or to a spiritual longing for immortality. Our discussion of the

orienting

properties of values implied their sway over the formulation of

interests. Let

us go back for a minute. The orderly orientation provided by values

will, of

course, bring about control over the hypothetical loose and direct

passage from

wants to satisfactions which may have existed in the state of nature.

It

provides a field which in the social context regulates drives towards

filling the

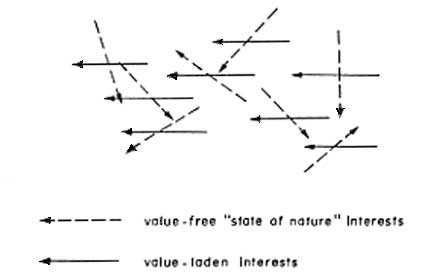

lacuna. But if you look at the position of the arrows in Fig. 4.02, you

will

notice that in the field provided by values, both needs and the

direction of

their fulfillment are modified from their original state-of-nature

position.

That is why in our Fig. 4.01, which was originally inspired by the

concept of a

magnetic field, we placed needs and goals at a lag. Any of our examples

of

interest-value relationships will make the point. For instance, you may

seek

wealth for what it can buy. But in the process of becoming wealthy your

assortment of needs may change and eventually you may consider wealth

itself as

the goal. And if you go after wealth honestly, you may never become

rich, thus

consumed by the value on your way to achieve the goal.

In the state of nature

the social unit, the individual

(illustrated by arrows representing a molecular magnet in Fig. 4.02),

might

have been only a short way from satisfaction for a given want—with a

small

chance of getting it, to be sure, but nevertheless at a short distance.

Once in

the field provided by values, he may have to go through a whole social

process

without necessarily reaching his original goal which, as

our-illustration

suggests, may lie aside from the path which his values provide for his

behavior:

Fig.

4.03

Of course, the

stronger the field created by the value

system in its orienting properties, the less relevant our statement

about

modification of interests and goals. When the value field is not strong

enough,

the subject, feeling the pull of his original drives and goals, may be

inclined

to deviate to satisfy them in a value-free, state-of-nature way. But as

the

pull of the value field intensifies, it overpowers the original drive,

which

must then be taken into account less and less. The lacks that the

individual

seeks to fulfill in the social context cannot always be satisfied by

the

nearest sources. Man has sexual drives, for example, but the incest

taboo makes

him impervious to his children. Our example indeed makes the point that

a

supply may be intrinsically abundant yet be rendered scarce and its

attainment

made subject to certain values in order to regulate its social

distribution and

to create motivations within the group members beneficial for group

interests.

If values can play a

role in making scarce what is

abundant in order to orient interests, it is reasonable to conclude

that they

will also influence those areas where the supply is intrinsically

scarce, in

which case the orientation provided by values is even more crucial,

since there

is not enough to go around. The value system must orient interests

toward their

goals so as to explain and justify the multiple standards which will

permit

some but not others to attain certain goals. The value system will have

to

supply comfort and compensation for those interests which have been

allotted

lesser satisfactions. There again, depending on the impact of the value

system,

we must qualify our statement about the intrinsic scarcity of the

resources

because, as the intensity of the value orientation increases, the

relevance of

our statement decreases. The ideal situation can be hypothesized as one

where

the value system is so well adapted to the social pattern that each

interest

flows towards its own goal orientation and finds its difference from

others

justified. The Sudra cannot be a Brahman; he was born a Sudra. And

those in Brave New World who are not supposed to

have roses are conditioned not to want them. It is when a value system

leaves

loose ends that the feeling of uneven apportionments becomes acute and

threatening. A value system which proclaims opportunity

for all leaves room for a good number of lacks to be filled. If it

does not

provide enough opportunities, it risks having those available

appropriated by

the opportunists and not by all.

Thus, it creates frustrations and

unfulfillable expectations, reducing the effectiveness of that

particular value

system for the group’s cohesion.

A value system, then,

may be called a framework within

which differentiations find justification. These differentiations, in

turn, if

the value system is efficient, provide the scale required to justify

discrepancies and set standards (render unto Caesar the things which

are

Caesar’s). In other words, not only does the value system orient,

adjust and

explain the place and domain of different interests, their title to

different

resources and the conditions for the attainment of certain goals, but

it is

itself contained within them. If eternity is beyond the mortal’s reach,

then it

is the eternal that will dictate the values to ensure life after death

and

salvation for man. If gold is scarce and imperishable (its permanence

defying

man’s destiny to decay), it becomes the standard and its possession is

good;

and those who possess it are those who control. If you are a Brahman

you may

set the rules, but in order to become a Brahman one must die and be

reborn. The

revelations of the eternal, the mercantile doctrine and the Vedic caste

systems

serve their social functions through their value charges (which may be

different

in different situations). By converting the functional into the

affectional,

values justify interests and their discrepancies and attenuate their

conflicts.

(By the same token, conflicting values enhance interest conflicts.)

Interests

in general, and sometimes some of them in particular, promote values.

Of

course, not all interests are value-laden. The difference between

values and

interests resides in their intensities and their possibilities of being

attained. Values, deep-rooted in the affectional and sublimated in

transcendental abstractions, are more intense and less negotiable.

Interests,

having attainable goals in view, compromise and negotiate on their way

towards

their ends.

The relationship of

values and interests becomes apparent

when conflicting interests find it time to compromise, while the values

justifying them lag behind. In such cases the mechanism is set to

modify,

reshape, dilute and disregard the values, or reinterpret and re-explain

them in

the light of other, superior values. Harun-al-Rashid recognized the

protectorate of Charlemagne, the emperor of the infidels, over the Holy

Places

in 807; the Crusaders finally settled down to coexist with the

Mamelukes in

1274; the Catholics and Protestants recognized each other as equals in

1648.

More recently, societies imbued with principles of free enterprise have

resorted to government control of the economy, such as anti-trust laws,

to ward

off crises inherent in their system of values, while regimes based on

Communist

ideals have adopted methods of liberal economy (such as the private

gain

incentive elaborated by the Soviet economist Liberman). On the

international

level, those who had fought Fascism a few years earlier accommodated

Fascist

Franco in the face of the superior Communist threat of the Soviet

Union, which

itself was later transformed into a negotiating partner and turned away

from

its former ally, China, accused of and accusing misinterpretation of

Communist

values. The latter, after 25 years of being an outcast of American

moral

standards, was visited by the President of the United States. The list

is

endless, as it is the very history of mankind.

V.

Metaphysical and Material Variations of Values

While the evolutions

and transformations of values

comprise human history, they are not apparent practices of everyday

life;

otherwise values and interests would become hardly distinguishable.

Values,

intense and irreducible, are latent to change. That is why interests

are turned

into values for their mainstay. This latency, however, is relative. In

the

examples above, the earlier value changes spread over a longer period

of time.

The mobility of the modern world, enhancing rapid social, economic,

technical,

political and ethical changes, develops variegated value structures and

attenuates

some of the transcendency, intensity, irreducibility and therefore

latency of

the values.[11] In a way, the dwindling of values in modern

society, while providing greater material possibilities for diversified

interests, also reduces the gap between values and interests. This, to

some

extent, explains the interchangeable use of the two terms by modern

philosophy

and social sciences. But the modern world is only a fraction of the

world, and

much of what happens in transitional and traditional societies, which

are far

from attaining the economic standards to satisfy their material

interests,

cannot be understood without the concept of value as discussed in the

last

pages. Besides, even the modern world is facing a value crisis. By

confounding

values and interests, by going increasingly after material

satisfactions, the

modern man empties his beyond of its substance. Yet values, besides

serving

social and material interests, are dimensions of human needs in

themselves: If

there were no God, man would have created one.[12]

Our examples of those

who were consumed in their élan

towards the attainment of their values were taken from earlier

Christian Europe

and more recent non-Western cultures, while our discussion of

materialism

centered around modern Western philosophies. The question thus arises

as to

whether there is a correlation between a society’s material development

and the

nature of its values. Without any pretensions of compartmentation, we

may again

attempt to differentiate in shades the relationship between the nature

of

values and certain social dimensions. When we were discussing primeval

subsistence economies earlier, we quoted Redfield as saying that under

such

conditions man called on the supernatural as support for his

livelihood. Other

social studies have shown that in more complex societies appeals to

salvationist religions are more frequent in the deprived groups whose

poor

material conditions in this world are made bearable by promises of

compensation

in the next world.[13] This goes along with Marx’s famous, but

often only partially quoted and therefore misunderstood statement:

“Religion is

the sigh of the creature overwhelmed by misfortune, the sentiment of a

heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium

of the

people.”[14]

When material

conditions provide for good living, the

focus of attention turns from the beyond to within, as has happened

through the

ages in different cultures, among different classes. The apogees of

Greek,

Persian, Roman, Chinese or Indian cultures had material traits similar

to those

of modern Western civilization. They differed from modern Western

civilization,

however, in that their material abundance often turned the appeal to

the

supernatural for livelihood into superstitious rituals. In other words,

abundance alone does not reduce supernatural values to materialistic

ideologies. For that, a dimension of empirical scientific inquiry is

needed.

Among the cultures listed above, those which developed at some time a

noticeably materialistic approach to values, such as the Greek and the

Chinese,

also had an inclination for scientific inquiry free from religious

dogma.

Modern Western culture

turned to scientific materialism

with the decline of natural law doctrines and the age of enlightenment.

Together with the fruits of the industrial revolution, progress and the

ideals

of social justice, material well-being (the good life) became the

ultimate

goal. Life was considered worth living and became a value in itself.

And the

value-polarization of interests on the way to their goals was conducted

within

a comparatively closed field, of which the sanctity of human life and

being was

the approximation rather than consummation of the beyond. ‘But even in

that

context, the man who, striving for power and deference, rationalizes

and wraps

his drive in his great concern for public

interest,[15] may himself become wrapped up in his own

rationalization—a process which lays ground for modern values: ideas,

ideals

and ideologies. This is the process which produces public figures like

Jefferson, Robert Owen, Sun Yat-Sen and Gandhi, who subordinated their

own

power positions to their dedication to a cause.

Despite the

metaphysical-material dichotomy suggested

here, then, there exist different processes of value-building—some

relying on

supernatural sublimations, others emanating from material

rationalizations. In

our next chapter we will examine this aspect of our topic and discuss

the

crystallization of values through beliefs, myths and ideologies.