|

Is there a set of absolute values – God-given, Krishna-given,

Allah-given – which should guide man's conduct and social

behavior? If so, which one? Or are values meaningless, as

Ayer has suggested? And if so, what does the word "value" stand for? To

answer each of these questions to the satisfaction of either the

normative or the non-cognitive school of thought will exclude the other

position. Yet, dialectically speaking, the existence of one implies the

existence of the other. Caught in the middle, the social scientist is

often inclined to avoid the issue by confining himself within an

operational system. Values, as realities of social life, become

structural ingredients of such systems, but their nature is

usually left undiscussed as beyond the confines of the system.[1]

In the following pages a brief remedial attempt is

made in two directions - on one hand through an incursion into the

empirically elaborated theories of social systems, with an inquiry

about the organic nature of their concepts of values (a scrutiny, in a

way, of the link between the two components of Parsons'

value-orientation pattern/action system constellation);[2] on the

other hand by an excursion from within the social sciences context

towards the metaethical normative and the positivist spheres. I am not

so much trying to get involved in a philosophical debate, as to explore

the possibilities of a synthesis which could hopefully throw some

light on the conceit of values as social phenomena. My approach is

"socio-phenomenological" in that I will examine "values-in-themselves,"

as realities of social experience. Of course, in both the

phenomenological and the social sense, "values-in-themselves" cannot be

dissociated from their existential reality.[3]

It is in this dual context that I will deal with them here.

I.

Interests

Man as an animal, and as a social animal, has certain patterns of

behavior conducive to the fulfillment of his physiological,

psychological, and sociological needs. For example, when he is hungry

he needs to eat, when he is tired he needs rest, when he is confined he

needs freedom, and when he is bondless he needs attachment. All along

he has "needs." And these needs are flexible, retractable, and

expandable. The Yogi of India can live on an almond a day, while the

Western man reaches for the moon. Within these broad limits some needs

may seem more justifiable than others. Caught in a blizzard, a man will

need a shelter lest he not survive. That need is imperative, while the

desire of the owner of a comfortable suburban house to upgrade his

dwelling into a mansion may be considered dispensable.

You may have noticed the word "need" in one case and "desire" in the

other. Although the two terms are often interchangeably used, in a

spectrum of wants ranging from imperative necessities to trivial

frivolities, we may call our longing for the former a need, and our

longing for the latter a desire. There is, of course, no clear-cut

dichotomy; and one term turns into the other depending on the social

context in which it is used. For example, the desire of the man to

replace his suburban home with a mansion may be classified as a need by

many people. If he has been promoted to the presidency of an important

firm, he may have to reside in a mansion to fulfill the social

obligations attached to his position. As it is in the interest of the

man caught in a blizzard to find shelter, so is it in the interest of

our executive and his firm to acquire a mansion. These interests

provide functional spheres making life and social life possible. When

we talk about "self-interest" or "national interest," we are referring

to functional spheres believed expedient for survival. I was tempted to

say "well-being" instead of "survival," for it is not a question of

mere existence, but the quality of it. In Aristotelian terms, the state

did not come about only for the sake of life, but for the sake of the good

life.[4]

The concept of good is, of course, in itself relative; but man claims

the faculty of choice, and that implies a scale of preferences.

Although we have elaborated no hierarchy of preferences so far, we have

implied an order of importance in which the immediate needs for

survival, such as food and shelter, seem to precede other needs. The

statement is obviously elementary. We know that, for example, through

the intervention of his intricate organism, man, like some other

animals, may renounce his food or his rest in the face of danger. In

fact, the history of mankind is filled with instances, like that of the

Japanese Kamikaze, where men have thrown their very lives onto scales

where conservation did not weigh the heavier. The loci of security and

conservation are at times displaced from individual security and

conservation to preservation of the group, nation, empire, fatherland,

principles, religion, or whatever the cause of the sacrifice. Faced

with the choice, man may prefer to die rather than renounce his

country, creed or ideology. The proposition is, of course, extreme. But

as long as the ultimate is not present, many will pretend to believe in

sacrifices they really would not be prepared to make. Nevertheless, man

is faced with choices, and in choosing he simultaneously conforms with

and participates in the elaboration of a scale of preferences in which

his very being, although certainly essential, may not always occupy the

first place.

If that is so, then is it that life and what is good for it are not the

key to the secret of man's preferential scale?

II. Problems of Interest-Value Dichotomy

To answer the question we may start by trying to detect differences in

the nature of the situations we have so far illustrated. We may notice,

for example, that what was described as the interest of the

newly elected president of the firm to upgrade his domicile could, in

the appropriate group context, correspond to certain "functional"

dimensions of social relations. On the other hand, it would be

difficult to explain the functionality of an individual's or a group's

sacrifice of its well-being and even its very existence for the defense

of an ideal. Such behavior does not seem to emanate from material and

functional motivations. It is non-rational and affectional in nature.

Although abstract, it does overlap and compete with the concrete and

material phenomena we have termed interests. In the scale of

preferences, it constitutes values as distinct from valuables.

When the believer donates his fortune to his church, he parts

with his valuables for his values. Without any attempt at a watertight

compartmentation, we may reasonably propose that while interests are

formulated more on the basis of functional-rational considerations,

values appear to pertain to the affectional-non-material dimensions of

human behavior. The distinction should be applied with caution, as

interests and values merge into each other and, as we shall see later,

generate and justify one another.[5]

The concrete-abstract dichotomy between values and interests has

received different degrees of emphasis by different scholars. Fallding

distinguishes between value, which is the "generalized end that guides

behavior toward uniformity," and interest, which is sporadic.[6]

Van Dyke treats them more or less as synonymous.[7]

Still others, Easton for example,[8] have

contained the concrete-abstract dichotomy within the different

connotations they have given, in different contexts, to the term

"value."

Some

studies treat values simply as part of a means-end relationship.

Lasswell and Kaplan distinguish between two sets of values: welfare

values, those which are for the benefit of the individual (such as

health, wealth, and enlightenment); and deference values, those which

imply interpersonal position relationships (such as power, respect, and

affection[9]). In this classification values may constitute

goals in themselves, or instruments to attain other values which then

become goals. Lasswell and Kaplan are concerned with values as of the

moment when they become perspectives and instruments in the context of

power,[10] and circumscribe the definition of value to fit

that framework.[11]

Some philosophical schools have reduced the study of values to the

verifiable facts approach of logical positivism. Values do not

represent facts and therefore the philosopher can proceed to declare

them, as Ayer has done, non-sensical.[12]

And legal positivists, like Kelsen in his Pure Theory of Law,

present us with a value-free concept of law basing its validity on a

system of norms.[13]

Kelsen does not deny the existence of intangible, abstract values, but

considers that they lie beyond the purview of scientific inquiry.

A phenomenological examination cannot be limited to classifying values

into the perspectives and instruments of power and politics; we must

dare to penetrate that hazy, intangible realm which values inhabit. The

inquiry into abstract values may prove profitable by revealing

similarities with those more concrete values that are instrumental in

the power complex. Such a possibility may permit us to close the gap

between values and interests. However, our concern here is not so much

to discuss the metaethical dimension of values, but to scrutinize

values as social phenomena. We wish simply to ponder the what, the why,

and the how of values. It is in this frame of thought that our earlier

discussion of the interest-value dichotomy and the following treatment

of their insularity are elaborated.

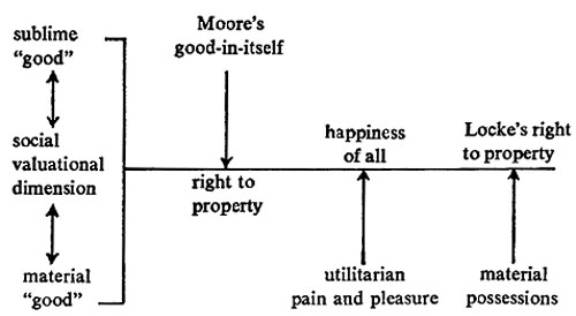

In different schools of thought, the term "value" has been used with

connotations covering practically the whole spectrum from material

interests to sublime values. At the "interests" end of the

spectrum, where we speak of the ontological, functional, factual,

descriptive approach - the idea of interest as goods - the term

"value" (the valuable) is used in the material sense. It covers

physical, mathematical, and even social scientific quantification, such

as the Marxian treatment of surplus value. Along the spectrum we touch

on the teleological and utilitarian idea of good as that

defining the desirable end, in the material sense of seeking

pleasure and avoiding pain, but with implications of qualitative values

of happiness. Finally, at the other end of the spectrum we encounter

the "higher" level of values, which, in their full moral and ethical

connotation, may refer to deontological or affectional imperatives

defining an idea of good which is good in itself, beyond

matter and man, and towards which man should strive. We cannot, of

course, extend our use of the concept of value so broadly as to cover

all these connotations without getting involved in apparent

philosophical contradictions. If, however, we conduct our study at the

level of social phenomenology rather than metaethical inquiry, we may

avoid the contradictory levels of different arguments and hopefully

bring them around to some common ground.

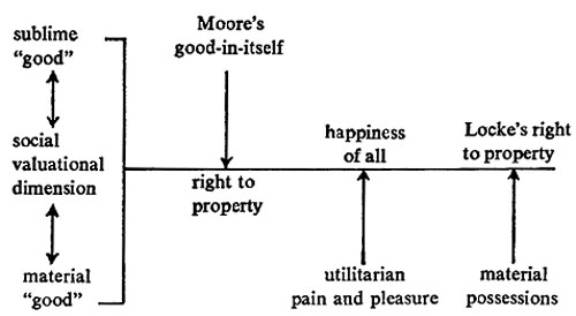

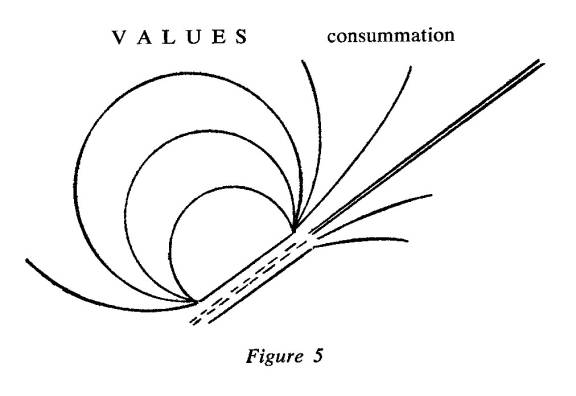

Through the various philosophical approaches seems to run a thread

which makes their treatment of values meaningful for our purposes. For

example, even at the material level, where values are interpreted as

"goods," their conversion into property gives them a social valuational

dimension which we may retain for our discussion. Thus Locke goes all

the way back to Adam to give his concept of property religious and

moral justification,[14]

putting it on a par with the right to life and liberty. Similarly, the

concept of utilitarians like Mill[15] of

avoiding pain and seeking pleasure is not built on the simple premises

of satisfying primitive desires, but on the enjoyment of virtues and

the general collective happiness. This concept provides a social

valuational standard beyond individual interests, embracing virtue

and religious morals.

At the level of philosophical treatment of good-in-itself and intrinsic

values we can find premises equally conducive to a valuational

dimension of social significance. Thus Moore, whose search for "good in

itself" bore the fruit of his famous naturalistic fallacy, denying

metaethical naturalism's claim to goodness in the nature of things,

notably in pleasure as advanced by the utilitarians, does nevertheless

recognize that:

The tendency to preserve and propagate life and the desire of property,

seem to be so universal and so strong, that it would be impossible to

remove them; and, this being so, we can say that under any conditions

which could actually be given, the general observance of these rules

would be good as a means .... On any view commonly taken, it seems

certain that the preservation of civilized society, which these rules

are necessary to effect, is necessary for the existence, in any great

degree, of anything which may be held to be good in itself.[16]

Here again Moore provides us with a social valuational dimension. It is

this dimension, whether it is converted from material "goods" or the

ethical "good," that we want to examine.

Figure 1

III. Problems of

Interest-Value Insularity

Our earlier distinction between interests and values concerned the

degree of their finitude. An interest can be identified, formulated,

striven for, attained, and finally consummated. Once the object of

interest is procured, the goal is attained and the end is reached.

While other similar interests may arise in time for the same

individual, they will all be different and separably definable in

means-ends terms. But values like love, patriotism, and piety, are not

ends attainable once and for all. Values that imply finite ends

eventually fall into the functional category and are therefore closer

to interests. A value must continuously be affirmed. An act of faith,

for example, does not absolve the actor of his faith, but merely

manifests the belief that lies beyond and that continues even after the

act is over. The goal is beyond the act, and because of the very act,

beyond the actors. In contrast to the functionally definable interests,

values lie in the affectional sphere. They are values because they can

only be approximated functionally. If they were attained, if they were

consummated, they would cease to be values. In the words of Sartre,

"Value is always and everywhere the beyond of all surpassings."[17]

The ultimate effort of man in the sphere of his value is to be consumed

towards its attainment, as were the Christians facing the lions in

Rome, the burning Buddhist monks in Saigon, and the Kamikazes.

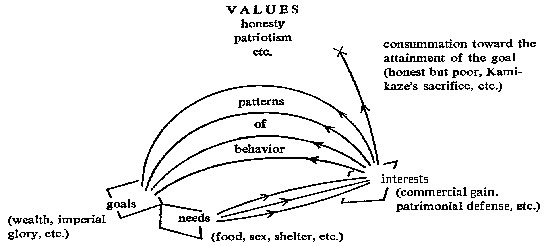

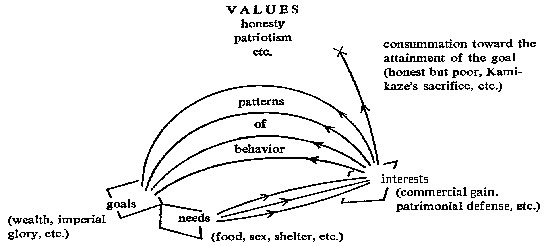

Different natures and dimensions of interest-value relationships can

fit our model. For example, speaking of commercial profit as an

interest, fair play and honesty as values, and wealth as a goal; or of

defense, patriotism, and glory as interest, value, and goal

respectively, we may visualize our model as follows:

Figure 2

Man's behavior, then is motivated by a pattern of interacting and

intermingling functional material interests and affectional

transcendental values. Some interests are more directly goal-oriented

and value-free, while others, in an increasingly transcendental scale,

are polarized and value-laden. As observed earlier, the gradation from

functionally goal-oriented interests to transcendental values does not

necessarily parallel the gradation from man's physiological needs for

survival to his metaphysical sublimations. The very goal-directed

physiological needs may themselves be conditioned by values. Between

the appeal to a prostitute for satisfaction of the sexual drive, a

functional extreme, and the romantic love which may culminate in

sacrifice, there is a wide spectrum of interest-value combinations. Not

only are these patterns not identical for different individuals, but

they may be different for the same individual under different

circumstances.

How do these patterns of behavior come about? To answer this it may be

helpful to shift our focus to the "social" part of the "social animal."

The group as the unit of identification needs to set a pattern of

behavior for its members in order to secure its cohesion. The

togetherness of the group under given conditions presupposes

already the existence of a group pattern of behavior. But both that

pattern and the togetherness may be caused by the given conditions

which may be external to the group. For the group to secure its

continuity despite the given conditions and not because of them, the

pattern of social behavior of its components should be instilled

(ingrained) in them. The wider and profounder the bases of

communication and communion, the more stable and long-lasting will the

group members' sense of belonging be. But what is the content of

communications, and what fills communion?

The survival of the group, the security of its existence, and its

interests in the material and functional sense depend on the conviction

of its members as to the validity of the group itself. This validity

must be more than the sum total of the private material and functional

interests of the components of the group. Without such a transcendent

validity, there would be no sense in risking one's life as a patriotic

soldier on the front.

The

pattern of behavior is enveloped in a sense of "oughtness," making

conflicting interests reconcilable and giving the individual a sense of

values.[18] To create this sense of values, in its

process of socialization the group appeals to certain ingredients of

human nature, and matches certain affectional dimensions and

transcendental feelings - values -with functional premises that provide

for material interests. For example, paternal love provides heritage,

faith maintains the church, and patriotism secures the existence of the

state.

Appeal is made to man's non-rational and affectional inclinations to

reinforce and coordinate the interests which are functional from the

point of view of group rationale, but which may not always directly

coincide with the individual rationales of its members. When a man is

hungry, he wants to eat, and he must eat to survive. But if he belongs

to a primeval superstitious group, and the available food is a totem

animal, and he eats it, he may go into convulsions and die a voodoo

death.[19]

In this extreme example the organism responds to the supernatural value

more intensely than to the material interest. The values of the group

act on the group member as stimuli and go through his organism, which

processes them before responding. The more the value is straightforward

and recognizable as a value, and its impact regulated and controlled,

the less will the organism be confused in its response. The efficacy of

the value will depend on how well the organism has been conditioned to

give the desired response to it.

The voodoo death is the extreme of such conditioning, but it helps us

demonstrate rather dramatically the vast gap that can exist between

values and interests. The taboo on sacred food emphasizes the value

that safeguards the group's structure. But groups are not

amorphous, and in the last analysis, their interests and structures

should reflect the interests of their members. In the words of Latham,

"Groups exist for the individuals who belong to them, by his membership

in them the individual fulfills personal values and felt needs."[20]

If certain values instilled in group members can be detrimental to

their interest in physiological survival and security of livelihood,

then they must correspond to some other drives of the individual

members. If order and justice are prerequisites for the continuity of

the group, it is because they are manifestations of man's inner need

for predictability. If for cohesiveness the group develops a sense of

identity and communion among its members, it is because it can appeal

to man's psychological need for contact comfort and belonging. And if

the supernatural belief can bring about a voodoo death, it is that

there exists within man a drive to search and fear the unknown. Thus,

despite the gap between them, both values and interests are phenomena

relating to the reality of man and his basic needs and drives.

If man's drives are the raw material for both his values and interests,

then their common origin may imply an organic relationship between the

two. What kind of organic relationship can that be?

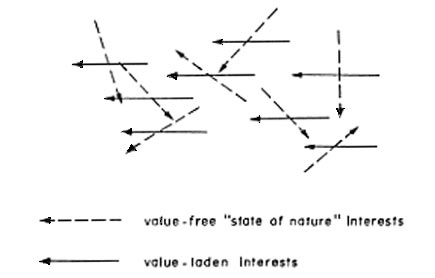

IV. Interest-Orienting Properties of Values

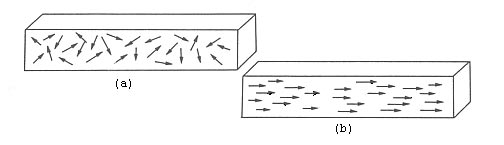

Man's drives and the search for their proper sources of satisfaction

are generated by his consciousness of lacks, whether of food,

attachment, or eternity. As we saw earlier, an interest is the

formulation of a want and the move towards filling the lacuna. But if

the move is haphazard, different interests may - and in a social

context are bound to - come into conflict, jeopardizing the social

pattern conducive to the satisfaction of the drives. The passage from

interests to goals will therefore need some sort of orientation,

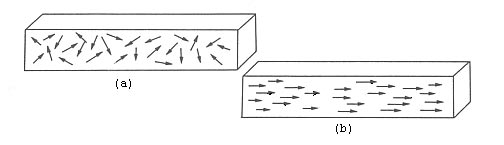

like the molecular magnets in a steel bar which are randomly oriented

when unmagnetized, but which line up parallel from one pole to another

after magnetization:

Figure 3

Values provide the field for this orientation of interests. But as

molecular magnets are the same before and after magnetization, except

for their charge and their direction in the magnetic field, so are

interests before and after orientation, except that some have been

sublimated by values. What we said earlier about the appeal that is

made to the non-rational, affectional dimensions of man to direct the

rational and functional should be completed by the statement that

the appeal is not the point of departure of a relationship between two

properties otherwise foreign to each other. There is no such abstract,

independent value as patriotism and another totally separate entity as

a fatherland; rather the two are coupled to create an interest-value

constellation which gives meaning to man's need for territorial

belonging. The organic relationship between the affectional and its

corresponding functional - the value that orients the interest - is

causal. Interests and values grow on and into each other. We are thus

closing the gap between values and interests, but not to the extent

pure interest theories do. Values and interests are not totally

identical. To say that they are identical is like saying that

flashlight beams and laser beams are the same because both are the

propagation of light by photons, ignoring the proportionality of

their energy and frequency. Transferring our simple metaphor, we

may say that values are the conversion of interests beyond apparent

recognition. Like the laser and the flashlight, values and interests

are similar up to a certain point of frequency, intensity, and

concentration, but beyond that, the phenomenon reveals different

impacts and consequences. Liking and wanting become loving - the

extrapolation of the ego. The interest in security and survival becomes

patriotic sacrifice.

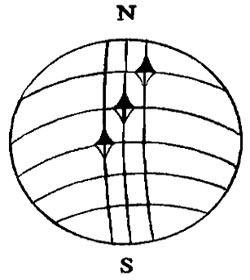

We used the analogy of a magnetic field to explain the orienting

directing characteristics of values, and we used the intensity and

frequency of laser photons to illustrate their impact and penetration.

In physical terms, the process of the projection of photons in a laser

is distinct from the magnetic phenomenon. Yet the visualization of a

value system as providing a "magnetic" field to orient interest-goal

movements and thereby create a forward impetus is not necessarily

contradictory for our purposes. Let us, in our first analogy of the

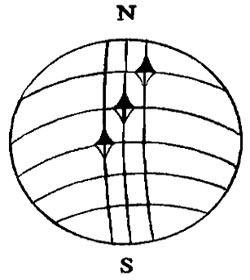

magnetic field, conceptualize a magnetic flow between a pole and an

opposite outside pole, such as a compass needle and the magnetic field

of the earth:

Figure 4

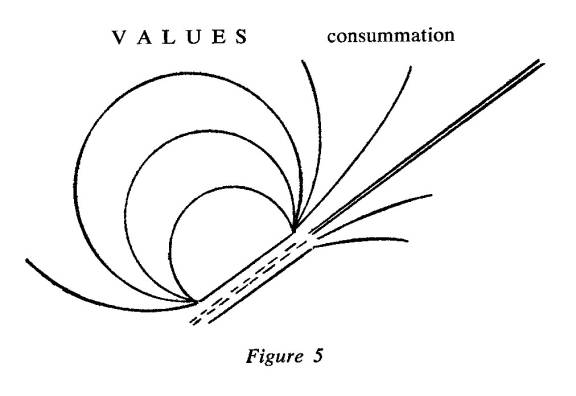

We may then visualize the value-interest constellation, in the process

of providing an orientation within a closed magnetic field,

accelerating and projecting the motivational flow of some towards a

point beyond the closed circuit, comparable to the flow of photons in a

laser:

This flow, which we

explained earlier as the consummation towards the attainment of the

value, can be appropriately illustrated by the photons which on

reaching their target are annihilated and become energy.

Drawing

further from our laser analogy, when man's behavior is strictly

controlled and directed with intensity within a field of values, he is

capable of deeds and behavior otherwise beyond the common realm of

human achievement, such as the sacrifice of the Kamikaze or the early

Christian or Moslem believer. Like the laser, in the process of

orientation and intensification, values narrow their field and isolate

the subject from his surroundings. But our illustration does not follow

the metaphor to the end, because, unlike the laser, the consequences of

valuational rigidity may, for example, turn faith into fanaticism and

fanaticism into superstition, thus reducing the efficacy and

penetrating properties of values and increasing the group's

vulnerability.

The

examples of intense value orientations so far mentioned have been

chosen because of their social and political relevance. There are, of

course, other instances, such as conscious concentration in value

orientation, which also lead to uncommon achievements. We now have

scientific proof that at a high level of religious meditation, man can

transcend toward the sublime in consciousness. Recent experiments by

the application of the electroencephalograph on Zen and Yogi meditators

have shown the possibilities of controlled alpha waves in the brain and

consequent attainment of peaceful plenitude. Discussion of such

dimensions is beyond the purview of this paper, but just consider their

possible future political implications as alternatives to Orwell's 1984.

V.

Interest-Justifying Properties of Values

Our discussion of the need for a field to regulate the passage from

drives to satisfaction within the group implied the likelihood of clash

between different interests in the absence of a value field. The

Hobbesian state of nature would tremendously reduce the chance for

drives to receive satisfaction. Without the field of values, the

eventuality of filling the lacuna would be scarce, whether the basic

material for fulfillment was abundant or not. Maybe we should emphasize

that the idea of a lack does not necessarily refer to an absence, but

rather to the consciousness of its possibility. It is not, therefore,

so much the intrinsic abundance or scarcity of a supply, but man's

subjective want and consciousness of that want that provide grounds for

the formulation of interests, elaboration of their orderly orientation,

and their sublimation into values. Man's subjective perception of a

want, independent of the abundance or scarcity of its supply, implies

that a lacuna can be produced, displaced, magnified or reduced by the

intervention of values.

As before, we use the concept of lack and scarcity globally: it may

refer to a physiological lack such as water or food, or to man's

longing for immortality. The orienting properties of values suggest an

influence over the formulation of interests. The orderly orientation

provided by values will, of course, bring about control over the

hypothetical loose and direct passage from wants to satisfactions which

may have existed in the state of nature. It provides a field which, in

the social context, regulates the passage of drives towards the filling

of the lacuna. But if you look at the position of the arrows in Figure

3(b), you will notice that in the field provided by values, both wants

and the direction of their fulfillment are modified from their original

state of nature position as shown in Figure 3(a). That is why in Figure

2, which was originally inspired by the concept of the magnetic

field, we placed needs and goals as we did - at a lag.

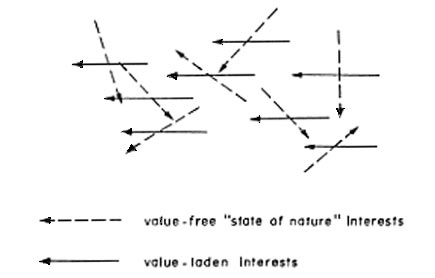

The social unit, the individual (illustrated by arrows representing the

molecular magnet in Figures 3(a) and (b) and 6) might have been only a

Figure 6

short distance from the satisfaction factor for a given need in the

state of nature - with a small chance of getting it, to be sure, but at

a short distance nevertheless. Once in the field provided by values, he

may have to go through a whole social process without necessarily

touching on what could have been the original source of his

satisfaction, which, as our illustration suggests, may lie aside from

the path which his values provide for his behavior.

Of course, the stronger the field created by the value system in its

orienting properties, the more irrelevant our statement about

modification of interests and goals. When the field created by values

is not strong enough, the subject, feeling the pull of his original

drives and goals, may have inclinations to deviate in order to satisfy

them in a value-free, state of nature way. But as the draw of the value

field grows in intensity, it overshadows the original drive, which will

then have to be taken less and less into account. The lacks that the

individual seeks to fill in the social context cannot always be

satisfied by nearby sources. Man has sexual drives, for example, but

the incest taboo makes his progeniture inaccessible to him. A supply

may be intrinsically abundant, but may be made scarce and its

attainment subject to certain values in order to regulate its social

distribution and to create motivations beneficial for group interests

within the members of the group.

Values will obviously also influence those areas where the supply is

intrinsically scarce. There, the orientation provided by values is even

more crucial, since there is not enough for everybody. The value system

must orient interests towards their goals so as to explain and justify

the multiple standards which will permit the attainment of certain

goals by some and not by others. The value system has to supply comfort

and compensation for those interests which have been allotted lesser

satisfactions. There again, depending on the impact of the value

system, we have to qualify our statement about the scarcity of the

resources which do not provide enough for everybody, because if the

value orientation reaches a certain point of intensity, our statement

becomes irrelevant. The ideal situation can be hypothesized as one

where the value system is so well adapted to the social pattern that

each interest will flow towards its own goal orientation and will find

its difference from others justified. It is when a value system leaves

loose ends that the feeling of uneven apportionments becomes acute and

threatening, for it thus creates frustrations and unfulfillable

expectations, reducing its effectiveness for the cohesion of the group.

A value system, then, may be said to be a framework within which

differentiations can find their justification. The differentiations in

turn, if the value system is efficient, provide the scale required for

justifying discrepancies and setting standards. In other words, not

only does the value system orient, adjust, and explain the place and

domain of different interests, their title to different resources, and

the conditions for the attainment of certain goals, but it is in itself

the system of those standards. The revelations of the eternal, the

Vedic caste system, and the mercantile doctrine serve their social

functions through their value charges. By converting the functional

into the affectional, values justify interests and their discrepancies

and attenuate their conflicts. (By the same token, conflicting values

enhance interest conflicts.) Interests in general, and sometimes some

of them in particular, promote values. Of course, not all interests are

value-laden. The difference between values and interests resides in

their intensity and the possibility of their attainment. Values are

more intense and less negotiable. Interests compromise and negotiate on

their way towards their ends.

The interrelatedness of values and interests becomes apparent when

conflicting interests find it time to compromise, while values

justifying them lag behind. In such cases the mechanism is set to

modify, reshape, water down, and disregard the values, or to

reinterpret and re-explain them in the light of other superior values.

Societies imbued with principles of free enterprise, for instance, have

resorted to government control of the economy, such as anti-trust laws,

to ward off crises inherent in their system of values, while regimes

based on Communist ideals have adopted methods of liberal economy. On

the international level, those who had fought Fascism a few years

earlier accommodated Fascist Franco in the face of the superior

Communist threat of the Soviet Union, which itself was transformed

later into a negotiating partner and turned away from its former ally,

China, accused of and accusing misinterpretation of Communist values.

The latter, after twenty-five years of being an outcast of American

moral standards, was visited by the President of the United States. The

list is endless, as it is the very history of mankind.

VI. Metaphysical and Material Variations of Values

While the evolution and the transformation of values comprise the

history of mankind, they are not obvious processes of everyday life;

otherwise the dichotomy between values and interests would become

hardly distinguishable. Values, in their intensity and irreductibility

are latent to change. That is why interests are turned into values for

their mainstay. However, the mobility of the modern world, enhancing

rapid changes, develops variegated value structures and attenuates some

of the transcendency, intensity, irreductibility, and therefore latency

of values. In a way, the dwindling of values in the modern society,

which provides greater material possibilities for diversified

interests, reduces the gap between values and interests. This, to some

extent, explains the interchangeable use of the two terms by modern

philosophy and social science. But the modern world is only a fraction

of the world, and much of what goes on in the transitional and

traditional societies, which are far from attaining the economic

standards to satisfy their material interests, cannot be understood

without the concept of values as discussed in the last pages. Besides,

even the modern world is facing a crisis of values.[21] By

confounding values and interests, the modern man empties his beyond of

its substance. Yet values, besides justifying social and material

interests, are dimensions of human needs in themselves: If there were

no God, man would have created one.

The question arises as to whether there is a correlation between the

material development of a society and the nature of its values. In a

primeval subsistence economy, as Redfield says, "Gaining a livelihood

takes support from religion, and the relations of men to men are

justified in the conception held of the supernatural world or in some

other aspect of the culture."[22]

In more complex societies, appeals to salvationist religions are made

more by the deprived groups whose unfavorable material conditions in

this world are made bearable by the promises of compensation in the

other world.[23]

When material conditions become favorable and provide for good living,

the focus of attention turns from the beyond to within. The apogees of

Greek, Persian, Roman, Chinese and Indian cultures had material traits

similar to modern Western civilization. However, they differed from

modern Western civilization in that their material abundance often

turned the appeal to the supernatural for livelihood into superstitious

rituals. In other words, material abundance alone does not reduce the

supernatural values to materialistic ideologies. For that a dimension

of empirical scientific inquiry is needed.

The modern Western culture turned to scientific materialism with the

decline of natural law doctrine and the age of enlightenment. Together

with the fruits of the industrial revolution, progress, and the ideals

of social justice, material well-being (the good life) became the

ultimate goal. Life was worth living and became a value in itself. And

the value polarization of interests on the way to their goals was

conducted within a comparatively closed circuit, of which the sanctity

of human life and being was the approximation rather than consummation

for the beyond. It is in this context that objective relativism deals

with values. But the man who, striving for power and deference,

rationalizes and wraps his drive in his great concern for public

interest[24]

may himself become wrapped up in his own rationalization, a process

which lays grounds for modern values: ideas, ideals, and ideologies.

This is the process which produces public figures like Jefferson,

Robert Owen, Sun Yat-Sen, and Gandhi, who subordinated their own power

position to their dedication to their cause.

Despite the relatively closed curve of their value-interest

constellation, even the modern scientific, empirical, and material

contexts do then provide value-building processes. We may, therefore,

conclude that values are phenomena of man's reality of existence and

life experience in their own right; and that whatever the process,

whether through the supernatural idea of the holy or the ideological

rationalization for the righteousness of a cause, values provide for

the fulfillment of man's affectional and nonrational dimensions.

Through values man makes sense of himself and of his environment.

Psychology and social psychology have even provided us with means to

diagnose value deficiencies. Durkheim called the symptom anomie.

[1] This is an abridged version of a paper

delivered at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science

Association in Chicago, 1971.

[2] Talcott Parsons, The Social System

(Glencoe, Ill., 1951). The reader will notice the constant

implication of Parsons' theories in this paper. For the sake of

brevity, I have avoided footnoting the numerous references which would

have become cumbersome.

[3] The term "phenomenology" has received

a broad usage - from the transcendental phenomenology of Husserl to

existential phenomenology of Sartre in philosophy, the biological

phenomenology of Uexküll, the cultural phenomenology of Cassirer

and the social phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty and Schutz. Here we are

employing the term to emphasize the human reality of values and hence

their social reality. See notably our later Sartrian-inspired treatment

of value as that which is "beyond all surpassings" and "the lacked."

[4] Aristotle, Politics, Ch. V.

[5] See, for example, Clyde Kluckhohn and

others, "Value and Value Orientation in the Theory of Action," in

Talcott Parsons and Edward A. Shils, Toward a General Theory of

Action (Cambridge, Mass., 1951), pp. 388-433, where a distinction

is made between the desired and the desirable, with value being the

explicit or implicit conception of the latter, p. 395.

[6] Harold Fallding, "Empirical Study of

Values," American Sociological Review, 30 (April, 1965), pp.

223-233.

[7] Vernon Van Dyke, "Values and

Interests," in APSR, 56 (Sept., 1962), pp. 567-576, also

his International Politics (New York, 1966), p. 8.

[8] When Easton suggests that "political

science be described as the study of the authoritative allocation of

values for a society" he refers to "certain things" that "are

denied to some people and made accessible to others." (The

Political System, New York, 1953, pp. 129-130. My italics.) The

"values" he is talking about here are "things." They are different from

the concept he adopts later in another context where he says, "Values

are expressions of our preferences and essentially dissimilar to

factual aspects of propositions." (The Political System, p. 222.)

They differ also from the "regime values" with which he identifies

ideologies, doctrines, and social philosophies underlying political

practices. (A Systems Analysis of Political Life, New York,

1965, pp. 194 ff.)

[9] Harold D. Lasswell and Abraham Kaplan,

Power and Society, (New Haven, 1950), notably pp. 55-56.

[10] The treatment of religion and mention

of its relevance to political order in a footnote is indicative of this

approach. Lasswell and Kaplan, p. 194.

[11] Lasswell and Kaplan, Introduction, pp.

ix-xxiv. On the question of means-end limitations of values, see also

Gunnar Myrdal, Values in Social Theory, ed. Paul Streeten

(Evanston, 1958), Ch. X.

[12] For a representative exposition of

this approach, see Alfred Jules Ayer, Language, Truth and Logic (New

York, 1946), notably Ch. VI, pp. 102-119, and also pp. 20-22 of his

Introduction, where he defends his approach. See also his somewhat

modified approach in "Man as a subject for Science," in Peter Laslett

and W. G. Runciman, eds., Philosophy, Politics and Society (New

York, 1967), pp. 6-24.

[13] Hans Kelsen, Pure Theory of Law, trans.

Max Knight (Berkeley, 1967).

[14] John Locke, Treatise of Civil

Government, Ch. V.

[15] See John Stuart Mill,

Utilitarianism, Ch. II; also Ch. V.

[16] George Edward Moore, Principia

Ethica (Cambridge, 1903), pp. 157-158.

[17] P. Sartre, Being and Nothingness, trans.

Hazel E. Barnes (New York, 1966), p. 144.

[18] See Ralph Barton Perry, The Moral

Economy (New York, 1937), pp. 9-16. See also his General

Theory of Value (London, 1926); Fritz Heider, The Psychology

of Interpersonal Relations (New York, 1958), pp. 225-229; S. C.

Pepper, The Sources of Value (Berkeley, 1958). Pepper makes a

critical analysis of Perry's General Theory of Values in Ch. 9.

[19] See, for example, W. B. Cannon,

"Voodoo Death," in American Anthropologist, 44 (1942), p. 169;

C. P. Richter, "On the Phenomenon of Sudden Death in Animals and Man,"

in Psychosomatic Medicine, 19 (1957), pp. 191-198: and Robert

A. LeVine, "The Internalization of Political Values in Stateless

Societies," in Human Organization, 14 (1960), pp. 51-58.

[20] Earl Latham, "The Group Basis of

Politics: Notes for a Theory," American Political Science Review,

46 (1952).

[21] For some empirical data, see Clyde

Kluckhohn, "Have There Been Discernible Shifts in American Values

During the Past Generation,?" in Elting E. Morison, ed., The

American Style: Essays in Value and Performance (New York, 1958),

pp. 145-217.

[22] Robert Redfield, "The Folk Society," American

Journal of Sociology, January, 1947, pp. 293-308.

[23] B. Berelson and G. A. Steiner, Human

Behavior (New York, 1964), p. 394.

[24] Harold Lasswell, Power and

Personality (New York, 1948), pp. 21-38.

|