Power or Authority? ©A.

Khoshkish |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

|

PREFACE

The

antecedents of this inquiry go back to the late 1960's when a need was

felt to

examine power in itself in contrast to the then prevailing game theory

and

behavioral approaches to power (notably by Harsanyi, Dahl, March,

Gamson,

Bachrach and Baratz). The results of that study were presented to the

Midwest

Political Science Association in Chicago in 1971 under the title of

"The

Concept of Power: A Potentio‑Kinetic Approach". Many of the ideas

developed then have since become common concern in political philosophy

and

covered by many authors, permitting us to reevaluate and document

some of

those ideas.

But

the trend in the past two decades has become more and more normative

(Lukes,

Martin, Morriss, Isaac), ‑‑ some remaining descriptive (Nagel,

Oppenheim) ‑‑ with confining results. The reinjection of the

phenomenological dimension into the formal, descriptive and normative

treatments of power seemed again justifiable in order to keep our

perspectives

open.

The

results of the revisit to the topic were reported to the International

Political Science Association's Study Group on Political Power in

London in

1989. The present monograph is a reedited version of that report and is

prepared in proper printed form for the use

of colleagues and students who have expressed interest in our approach.

A

word on the "we" authorship of this monograph. A colleague inquired

whether it implied co‑authorship or, adding facetiously, it was the

royal

"we"! The answer was that it represented the traditional method

used

by authors who know that what they expound is the outcome of their

interaction

with their total environment. The alpha of this monograph's

authorship is lost

in time and space, somewhere between the Greek philosophers and the

legalists

of China, and its omega is Jacques Havet, respected friend and

colleague of

old, whose incisive comments on the last version of the manuscript

greatly

contributed to its improvement. To him and all go "our" thanks. But a

book is a living being. It communicates with the reader and the "we"

becomes the communion of the two. That communion is essential for our

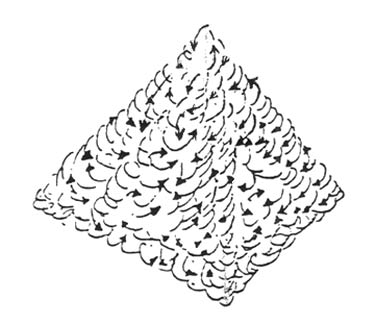

understanding. Power cannot be grasped as a string of elements but as a

complex

of thought. At all moments of our discourse its whole is present. Yet,

because

of the limitations of the written word all does not exude at once. That

is the

handicap of the writer compared to a painter who can unveil the canvas

once

completed. The writer has to beg for patience for the ideas that are

yet to

come and remind the reader of the thoughts that have flown by.

The

more obvious factor of the total environment affecting our study

is, of

course, the literature quoted or listed in our selected bibliography.

While our

search and research have been greatly influenced by the works listed in

the

selected bibliography we have not always had the occasion to quote them

in the

text. The purpose of this short essay is not to review the

literature referred

to or mentioned in the bibliography. We have our own approach to deal

with and

assume that those who get involved are either familiar with the

literature or

our mention of it will whet their appetite to seek it.

Although

the tone and tenure of this monograph is academic, if the practitioners

of

power cared to plough through it, they may find it not without

practical

interest. Philosophical discourse on power can provide food for

thought for

fathers, corporate executives, presidents, governors, and dictators who

are

concerned about the control of their domains. Whether it is the

imperative of

shifting weight within their spheres of power to remain on top or the

need to

perceive and evaluate resistants within their power complex, they can

draw

inspiration from abstract concepts for developing concrete

strategies.

This

revision has been undertaken during a period ripe with significant

events, from

the advent of perestroika in the Soviet Union and the unification of

Germany,

to the crises in the Middle East. Where appropriate, we have used

historical

examples for our concepts. The temptation to illustrate them by current

events

was great and we indulged several times. But succumbing to that

temptation

altogether would have made us chase those events and never finish the

monograph. Rather, it would be more interesting for the readers to test

the

ideas developed in this essay against current events; whether it is, as

these

lines are being written, our concept of Domination Drive against Boris

Yeltsin's bent for leadership, our analysis of the Spheres of Power

against the

dynamics of glasnost and perestroika or the German unification, or

whatever the

phenomena of the time may be. The test will permit the reader to mend

and amend

whatever is lacking in our understanding of power.

A. Khoshkish

New York City, May

1991.

I

INTRODUCTION

There

was power long before there

was a written word for it.

Charles E. Merriam

This

is an inquiry into the phenomenon of power: An attempt to examine power

as it

is in itself.[1] As Merriam's words emphasize, power is not

confined to human terms of reference. In that spirit, we intend to

extend our

inquiry to the limits of our perception and yet recognize that

power cannot be

circumscribed within those limits. Thus, our approach will take us

beyond the

strict study of power within the human societal context. True, as Dahl

says, we

shall have our hands full if we confine our study to the power

relationship

between human beings.[2] But

keeping our hands full with the human

dimensions of power for too long may narrow our perspective. Indeed,

following

Dahl's advice, recent studies of power have focused on its social

aspects and

immersed it in normative systems and begun confusing it with

ideology and

authority.[3] Surely law, authority and normative systems

contain considerable elements of power and vice‑versa. But

confusing

them muddles the issue.

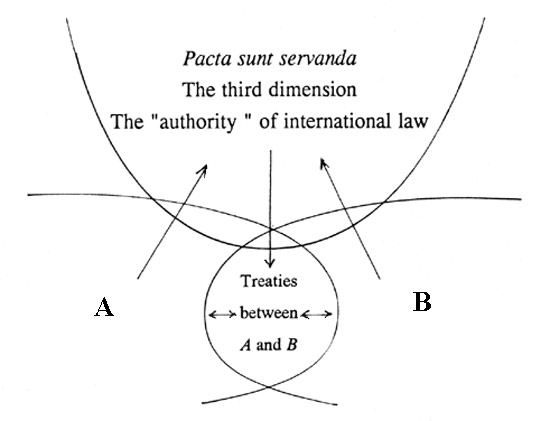

We

can better realize the dichotomy by moving to the confines of human

affairs. A

student of international relations, for example, is more sensitive to

the

phenomenon of power in itself beyond its convolution in normative

systems. From

an international perspective, normative systems, i.e.,

beliefs and ideologies, are more distinctly identifiable as

persuasion components for the legitimization of power within autonomous

complexes such as nations and states and are not confused with

power.[4] In the international arena, norms of

international law are often respected by powers which may not have

common value

systems. Beyond the two possible dimensions of conquest and defeat,

superior

and inferior, or power politics between entities which do not

recognize each

other's superiority or dominance and yet cannot overrun and absorb each

other,

powers create the third dimension of international norms to regulate

their

clashes and cooperation and to make the exercise of their power

reasonably

predictable.[5] "Raw" power eventually creates

norms and values for its own security and survival. But we are getting

ahead of

ourselves.

By

avoiding a total immersion in the societal context we may find premises

which

we could use to explain and overcome normative constraints.

Accordingly, while

perforce the thrust of our inquiry will also be human affairs, in

order not to

get too entangled in the ideological, legal and normative envelopes,

should our

analogies of social and natural phenomena coincide, in our search for

perspective,

we shall permit ourselves some digression. Our purpose in doing so will

be, to

borrow Bertrand Russell's words, "to suggest

and to illuminate, but not to demonstrate".[6] That may give our essay an

exotic

flavor. For that, we beg for the readers' forgiveness and appeal to

their

imagination.[7]

The

term entelechy in the title of this monograph has been borrowed from

the

Aristotelian theory of actualization of potentials.[8]

It has a dynamic and fermenting connotation. In strict physical terms,

potential is that which has not yet turned into kinetic energy, and

kinetic is that which by its motion has ceased

to be potential energy. The kinetic stopped in its course becomes the

potential

of its remaining energy. In other words, while on its course the

kinetic energy

carries with it the potentials of its continuity.

Potential

and kinetic energies are relative in their probability. Max Planck

always

remembered how his high school teacher Mr. Müller had told them

about the

conservation of energy:

"He

told us of the strength and power which a bricklayer needs

to lift

a huge stone to the roof of a building. The

energy is never lost. It remains stored up, possibly for years, latent

in the

block of stone ‑ until one day it is somehow loosened and, perhaps,

drops

on the head of some passerby ".[9]

Of

course the brick that is embedded in a solid wall, although a

potential head‑breaker,

presents less danger than a brick which sits precariously on the edge

of the

wall.

The

potentio‑kinetic concept hinges on convertibility. The potential side

of

the potentio‑kinetic concept of power corresponds to the Hobbesian

definition: "The Power of a Man,

(to take it Universally,) is his present means, to obtain some future

apparent

good".[10] But it is power insofar as the

relationship between the present means and the future good is a

dynamic,

materializable reality. This qualification of Hobbes' definition is

different

from Parsons' paraphrase to the effect that "‑‑ such

means constitute his (the Hobbesian Man's)

power, so far as these means are dependent on his relations to other

actor".[11] The two qualifications, the

dependence

of power on a relationship and its dynamic materialization, complement

each

other. It is in this existential and relational continuum that we

propose to

examine the concept of power.[12]

But

first let us see why and how man comes to perceive the phenomenon of

power. For

that we need to begin with the examination of the early

manifestations of the

phenomenon within the psyche and its role as the cue for the

identification of

the self in its total environment.

II

DOMINATION DRIVE

At the very beginning of its existence,

with its heavy brain and yet its weak body to carry it, the child

encounters

the realities of its contradictory being. Once out of the uterus it

finally

finds space to stretch and is, in a sense, freed from the confinement

of the

womb.[13] The fetus receives its oxygen, food and

warmth in the mother's womb, but is limited in its movements. Having

found

space at birth, the child soon experiences the discomfort of hunger,

and

changing temperature. It is at the

mercy of its parents' care for the satisfaction of its basic needs and

has to

submit to their rhythm. When it is hungry or uncomfortable, it cries.

Its crying,

which may be beneficial for its growth if the needs causing it were

satisfied

within reasonable biological limits, can turn into rage if frustrated.

Each of

these possibilities and the spectrum of other variations between

them will

have effects on the development of the individual's character and

personality.

Soon the individual becomes conscious of

his[14]

dependence on his parents.[15] His

dependence infringes upon his freedom

and imposes restrictions on him. At the same time he becomes habituated

to the

care he receives and develops an expectation for attention. The

degree of

attention received and expected will differ from family to family and

from

culture to culture. The child's expectation of attention goes

beyond the

satisfaction of his biological needs and relates to his needs for

affectional

relationships and contact comfort.[16]

This affectional attraction to the immediate environment, like the

attraction

for the satisfaction of biological needs, may meet a varying range of

responses. But even under the most favorable circumstances the

response cannot

provide total fulfillment for the affectional needs. To mention

but one

obstacle, the need for affection and attention and the response for its

fulfillment reside in different individuals. Even a dedicated and

loving mother

cannot meet her child's expectations of attention ex toto et

tempore, simply because expectations will evolve in relation to

their satiation.[17]

Thus the being, from the moment his

brain becomes capable of registering his experiences to the moment when

he becomes

conscious of himself as an individual, is constantly confronted with

situations

presenting limitations and possibilities. On the one hand they attract

him by

the security they offer; on the other hand they repulse him by the

dependence

they impose upon him. Attraction‑repulsion, love‑hate, and the

desire for freedom‑security are, psychologically speaking,

understandable

in their togetherness and mutual presence. It is the degree of

intensity of one

in relation to the other in a given situation that influences the

attitude of

the individual and makes him, for example, consider enclosure as

either

contributing to his security or confining his freedom. Thus, all

through life

man has to make choices between alternatives. By the very nature of

things he

cannot have his cake and eat it too.

As the individual goes through different

experiences in his life, first in his relations with his parents, then

with his

peers and his teachers, later with his colleagues and other members of

the

society, his dependence for security, freedom of action and

opportunities is

shifted to different sources. Of course, the optimum goal for him will

be the

possibility to control the sources on which he depends for his

security, thus

giving him freedom in their use and consequently "independence" from

them. In its more complex form security here includes not only the

fulfillment

of physiological needs but also the satisfaction of all of man's

drives, such

as affectional relationships which, while including the attention of

those who supply

him with his physiological needs, can also become more abstract and

cover such

expectations as recognition, admiration and respect. In other words,

all put

together the individual wants to be on top of the situation and

dominate it.

The child who cries for food to draw the attention of those who care

for him

and finally receives satisfaction, or who later charms his mother to

buy him

the candy he wants, already has some control over the sources of his

satisfaction.

The drive for domination, whether at the

level of child-parent relationships or in the arena of social and

political

struggle broadly follows the Darwinian law of the survival of the

fittest, or

in the present context, the dominant position of the fittest. The

domination

drive will, of course, be subject to other variables within the

social

complex. There will be neutralizing and propelling factors

influencing the

individual drives. The dominant position will not necessarily be

occupied by

those with the highest raw domination drive quotient, but by those who

reach

the power position in the flux of social dynamics and fermentations.

Thus, in

the omnipresent drive for domination, some will settle for more and

some will

have to, or simply will, settle for less. Those who do settle for less

extrinsically

(rather than going for the challenge of control and freedom of action)

have,

intrinsically (in their motivated behavior) opted for what they may

have

perceived as the path of least friction, or security provided for them

by the

powerful ‑‑ for fear of the unknown.[18]

In the evolution of a power

relationship, however, the dependence of those who have settled for

less on

those who dominate may eventually reduce the security the former

originally

sought. The goals of those who seek power for their own security and

freedom,

and who take control will not always coincide with the goals of those

whom they

dominate. In the extreme, the power-holders may develop a taste for

power as an

end in itself. It will be sought not only to provide security and

freedom, but

to give its holder the pleasure of overcoming resistance and making

others do

what they would not have done otherwise. Its exercise will be its

confirmation

and a source of satisfaction for other drives such as the drives for

excitement, game and challenge. Power may become engaged in a

spiral of

expansion.[19] Thus, depending on the circumstances, we

may detect different degrees of harmony, compliance, resistance

and conflict

in power relationships.

III

TYPES OF POWER RELATIONSHIPS

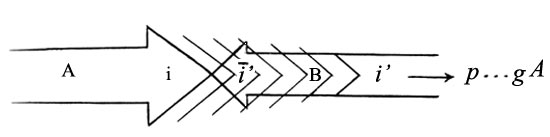

To

explore these variations, let us schematize a little.

Let A and B be power

complexes in a power

relationship.[20] Let us assume that when A wants B to act in a particular way (which we

will designate in each case as i', j',

k') it takes a particular action (which we will

designate in each

corresponding

case as i, j, k).

So, A performs i in order to make B

perform i'. Formally this is expressed

as (Ai |Bi' ). The two

variables

may combine in different ways, depending on the nature of the

relationship

between A and B and their actions, as

will be discussed in the following pages.

Under

different circumstances the combination may be that of simple

mathematical

operations of addition or subtraction, more complicated calculus of

vector

functions, or even scalar quantifications more appropriate for the

measurement

of mass and energy. The relationship will render a "product" which we

will designate a p; formally (Ai|Bi' ) → p. [21] The magnitude of p will, of

course, depend on the nature of the relationship and

interaction between A and B. The

power relationship in a power

complex matrix (which we will represent here for the power of A over B as P(A/B) may oscillate

between 1 and 0. That is

to say, A's power over B will tend

towards full power 1 when

every time A does i, j,

k, B does the corresponding i', j', k'. The power

of A

over B will tend towards 0 if every i,

j, k, action on

A's part encounters

noncompliance

or resistance on the part of B, which

we can represent as ![]() . In between, where there

is both compliance

and resistance (as is usually the case), B’s

response will represent the net result depending on which is greater.

. In between, where there

is both compliance

and resistance (as is usually the case), B’s

response will represent the net result depending on which is greater.

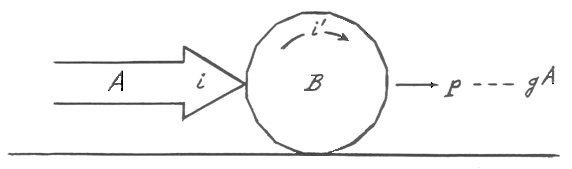

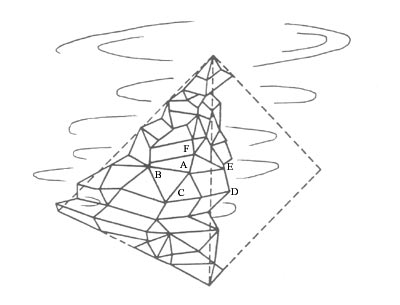

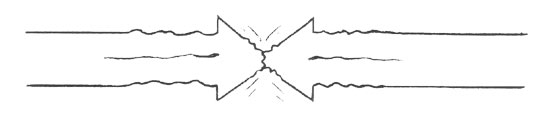

CATATONIC POWER RELATIONSHIP

Let

us first conceive of an extreme situation where the dominated element

is

catatonic, i.e., it presents insignificant resistance. It complies

not because

it finds that compliance corresponds to its goal, but because it has no

vigor

for self‑actualization. In psychopathology, catatonic schizophrenia in

some cases refers to what is called waxy flexibility, where the patient

can be

molded into different postures by others and keeps those postures for a

long

time. In the catatonic situation,

illustrated in Figure 1, B’s resistance

to A's action i tends toward

0 and A's power over B approaches 1

– formally, Bi’ → 0 and P(A/B) → 1.[22]

Figure

1

While A's power relationship with B approaches

the total unit, the

"product" of this power relationship may be 0 for A,

because the amount of resources A will have to

employ (which will be

identical with A's action i in the

catatonic situation) to make B perform i' may be nearly equal to i';

formally i'/i → 1, or i‑i' → 0.

Although

the product of the power relationship of A

and B may[23]

tend to zero, we may still consider A

as more powerful than B if the

proportion of A's total power

potentials to its action i is bigger than B's total potentials compared to its

action i'; formally, A/i >

B/i'. In the long run if A uses

a proportionally smaller amount

of its resources for actions i, j, k than

B does to perform its corresponding actions

i', j', k'

(assuming the same catatonic

relationship continues), A will not

simply maintain, but increase the ratio of its potentialities over B. This concept of proportionality will

be more obvious in the other kinds of relationships discussed later.

If B's resistance became zero, B would

cease as an independent power

and would be considered a component of A

‑‑ or its extension. The mention of this extreme, which can be

applied to human behavior only in rare psychopathological cases and,

with

qualification, to highly conditioned totemic subjects, calls for our

awareness

of such important characteristics of power as will and

consciousness. These

characteristics, which we shall discuss later, imply at this stage of

our study

that while B may be catatonic, A

should have a goal g in making B perform i'.

(Ai | Bi') will

render the product "p",

which may or may not be identical with A's

goal g. Also, p may or may not be

lucrative for A. As an illustration of the

non‑lucrative case, take the extreme

of power for the sake of power, which was mentioned earlier. Where A is a willful and conscious power, a

catatonic power relationship will not be much of a confirmation

for A's power and satisfaction, unless we

combine a megalomaniac with a schizophrenic. In that case, A's

exercise of power over B will

be like kicking stones on the road. In game theory language, our

catatonic

situation will approach the so‑called St. Petersburg Paradox, i.e., a

one‑person

game where one tosses a coin until he wins.[24]

If A's goal is lucrative, it is assumed

that in the catatonic situation the product, if any, will totally

accrue to A, formally (Ai | Bi') → pA. Of

course, we can conceive of a situation where A may

induce B to perform i' with part or

all of the product p

accruing to B. Take, for example, the case of the

catatonic schizophrenia given

as an illustration earlier. A may be

the doctor's power creating some will in B, in which

case because the result p

accrues to B, A will have less and

less of a catatonic relationship with B, and

their relationship may evolve into one of the other situations

described

below. If A's power over B is to continue in one way or another, the product of their

power

relationship

should be distributed so that a bigger part of it accrues to A's power potentials. For example, in

our last illustration,

while B gains more will‑power by the

doctor's Ai, he may at the same time

gain more conscious respect for the doctor's power. Thus, (Ai

|Bi’) → pA > pB.

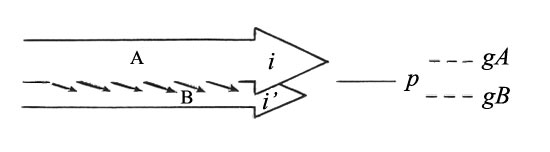

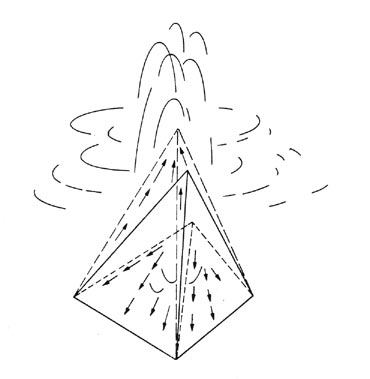

COMMENSAL

POWER RELATIONSHIP

"Commensal"

was the term used by Hawley to indicate the relationship between like

species

in their parallel efforts to make similar demands on their environment.[25] Its literal meaning is: "eating from

the same table." In our concept of power, a commensal relationship

resembles Harsanyi's model where A

can make B move from an initial

strategy to a second one more favorable to A.[26] Here Harsanyi's assumptions are implied. Let

us say that landowner A does action i,

which in our model can include

canalization for irrigation and land improvement, favorable lease terms

(Harsanyi's reward), and competitive pressure (Harsanyi's threat) to

induce farmer B to leave his present low yield farm

(Harsanyi's strategy one) to come and farm on A's land

(Harsanyi's strategy two). B's coming onto A's

farm

is represented by i'.[27]

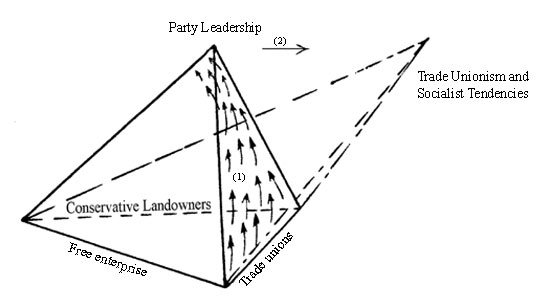

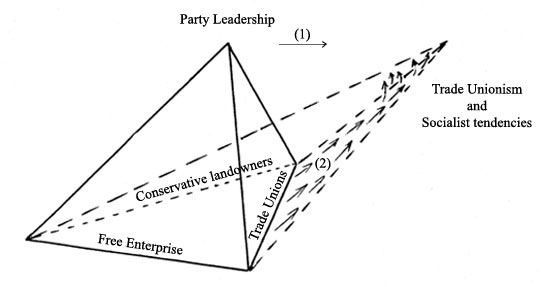

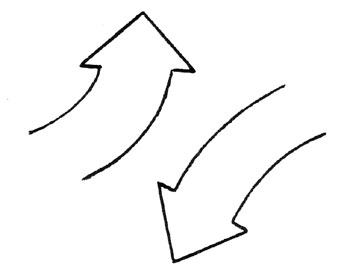

Figure

2

The

power relationship of the landowner and the farmer is commensal in that

they

have a common goal ‑‑ in the elementary sense, their need to eat.

Of course, the farmer B can farm his

low yield land and the landowner A

may have to farm his land himself instead of leasing it out. In such

case there

will be no commensal power relationship between A and B. There may be

other power relationships between the two which could fall into one of

the

categories that follow. By engaging in a commensal power

relationship they

increase their chances for a better crop (Figure 2).

The

product of their commensal power relationship may not be identical with

the

goals gA and gB which each of the

powers A

and B expect out of the relationship.

Landowner A may have planned on

benefits providing him funds for the expansion of the farm, while B may have counted on savings which

would enable him to procure a fertile farm of his own. Each one's goal

may

handicap the other and in their compromise they may not reach their

original

goals. The relationship may thus have, in Harsanyi's terms, utilities

and

disutilities for both partners and finally yield product p. Of course,

the

power relationship is commensal in so far as A and B have the primary

common goal of nourishing themselves. The more there are interests in

their

individual goals which are not compatible with those of the other, the

more our

model will tend to approach the divergent or conflicting power

relationships

explained below.

*

* *

Before

proceeding to other categories of power relationships, let us

retain some

aspects of this second model which will be useful for our later

discussions. In

general, as a result of A's action i,

B

will perform i'. Notice, however,

that landowner A's action i included

not only reward and threat

directly addressed to B, but also

land improvement and irrigation canalization, which are for A's

general welfare too. One might say

that these last items are independent of the power complex under

consideration. But they surely did influence B's evaluation and final

movement towards performing i'.

Let

us make the point by another illustration. Suppose A

is an excellent marksman and while he is performing i,

that is, is target shooting, he is

observed by B. Now, suppose he asks B to perform i' and B,

having been impressed by A's marksmanship

and assuming the

threat of A's gun, complies. Yet, A

may be a peaceful character who loves

target shooting as a sport but would not think of using his gun on a

living

being.[28] We will leave B's subjective

evaluation of A's

intentions and A's consciousness of

his power for a later stage of our discussion. At present what is to be

retained is that A's action i which

made B do i' was not directed

to B. Of course, a range of

situations may be conceived where A

may do i partly addressed to B and

partly for other purposes. A may have been shooting in

our example

not only for practice and fun, but also to impress B.

A military parade is simultaneously a festivity and a

demonstration of force to evoke pride in the citizens, to assure the

allies and

to threaten the enemies.

While

the consideration of all of Ai will

be useful for the understanding of B's subjective

evaluation of its power relationship with A,

only that part of i which has been exerted or spent by A directly to bring about Bi’ should be

taken into account for the assessment of A's

costs. This cost, as we said earlier, can include

expenses

other than direct reward and threat addressed to B.[29] We can represent this cost by is and

complement the formula presented in the case of a catatonic power

relationship

accordingly:

i' >

ic , A/ic >

B/i', p > O, (Ai | Bi') →

pA → pB

This,

of course, is a clear‑cut and straight‑forward potentio‑kinetic

power position for A. Because A's cost

is less than B's efforts, the proportion of A's cost to its resources is smaller

than that of the ratio between B's efforts

and resources, and a bigger portion of the end product accrues to A. Situations may arise, however, where

one or more of the favorable conditions may not exist and yet A may still be considered to have power

over B. Take for example the case

where A may have had costs greater

than B's efforts, or the ratio of A's costs

and resources was smaller than

that of B's, but that the amount of p

accrued to A was of such a magnitude that it

compensated for the other

unfavorable conditions. Or take the case where the ratio of A's costs

and

resources was so insignificant that although a bigger part of the

product

accrued to B, all in all A came out

of the deal more powerful.

Although, as we shall see later in our discussion of the nature of

product

"p", whether p corresponds to the goal

pursued by A and is compatible with it is crucial

in the determination of the outcome in the power complex.

It

should be noted that the difference between the catatonic relationship

and the

commensal (and those following) is that in the former no distinction

was made

between i and ic. The

rationale is that if B is catatonic,

it

perceives only A's action directed to

it and therefore,

for A, i is equal to ic.

Further, it may be

proposed that if a distinction is made between A's

action i and its cost ic

toward the A/B power

relationship, then B's action i'

should also be distinguished from its cost. The proposition

would make the distinction between action

and cost obsolete if it were applied

to both sides. The distinction in the case of A and

not in the case of B is

justified, because in our conceptualization Bi' is

only that action of B

which is directly and totally involved in the power complex, while Ai may also be involved in other

situations. Actions of B not related

to the particular A/B power

relationship are not counted in the equation in order to reflect a

clear power

situation. Of course, power situations are multi‑directional, and

we

will need to repeat our computations for each direction and

combine them for a

more complete picture. Formally, we may then combine the different

variables

into:

(i'+ A/ic + pA)

> (ic +

B/i'+pB) → P (A/B)

This

formula is not an all‑encompassing quantification for power, but is an

attempt at encapsulating the variables conducive to a power

relationship.[30]

It also applies to our discussion of power relationships that follows.

While by

attributing comparable units to their components we may use our formula

to

measure specific and confined power relationships, the intangible

dimensions of

power impede its general quantification. Our further discussions will

show, for

example, that under certain circumstances the interactions,

transactions and

reactions of the components of a power complex may follow more the

laws of

direct and inverse proportionality than simple operations of addition,

subtraction, multiplication and division.

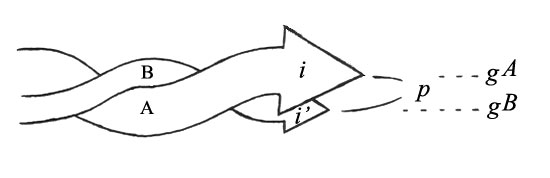

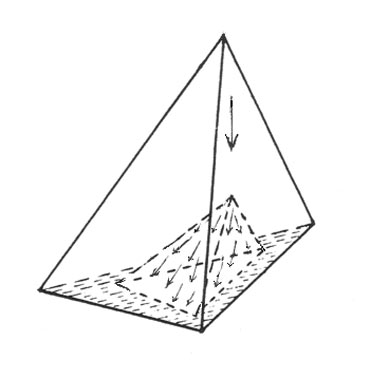

SYMBIOTIC POWER RELATIONSHIP

Symbiosis

here means interdependence and specialized coaction, involving some

degree of

mutuality between organisms of different kinds.[31] Defining symbiosis, Clements points out the

large and wide use of the term and adds that the mutuality of the

coaction can

fluctuate greatly from type to type. In our terminology "different

kinds" do not necessarily imply totally unlike species. Two countries

with

different resources, or two parties with different ideologies, may

become

involved in a symbiotic relationship. In our model for power, a

symbiotic

relationship is different from a commensal one in that it is not a

simple

association.

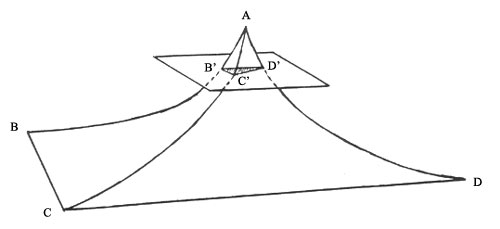

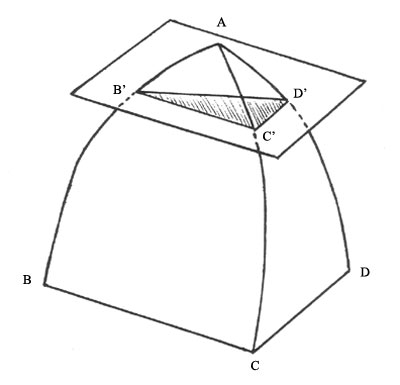

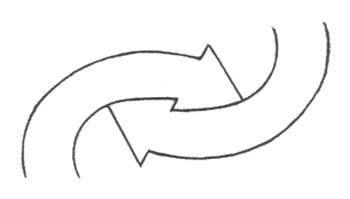

Figure

3

In

a symbiotic relationship as distinct from commensal, each of the

components A and B of the power

complex can move toward its goal only with the

participation of the other. The difference can be demonstrated if

we take our

last example of landowner and farmer and turn it into a

feudal‑vassal

relationship where the feudal prince is not much of a farmer and the

vassal

cannot have access to farmland without taking an oath of allegiance to

the

feudal prince for the land and his protection.

To

illustrate further, we may say that a commander without an army or an

army

without a commander makes little sense. Another example is the

negotiations

between the oil‑producing countries and oil companies.[32] The industrial societies of Western Europe

and Japan cannot function without the oil flowing from the countries of

the

Near and Middle East. Inversely, the oil‑producing countries need the

oil

revenues which subsidize their budgets and finance their economic

development

and military ambitions.

The

symbiotic model best illustrates the potentio‑kinetic continuum and can

be said to be most recurrent in power complexes, because the components

of a

power complex will usually combine, although the result will not be

equally

beneficial to the components involved. The bacterium may kill the

legume in the

long run.

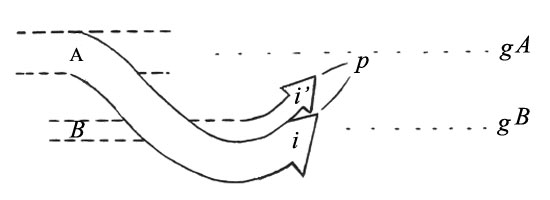

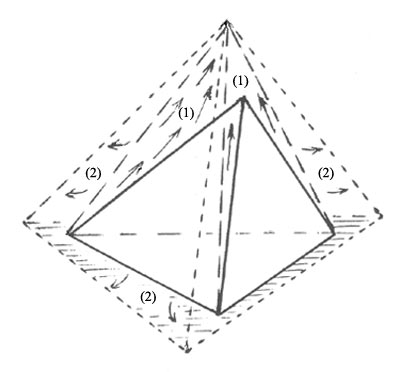

DIVERGENT POWER RELATIONSHIP

Here

we are presented with a model where the goals of A and

B do not coincide.

Or let us say, the model is for that part of A's and B's goals which

do not coincide, because divergent power relationships may coexist with

other

models. By divergence we imply that the interests of A

and B under

consideration are not on a collision course ‑‑ we are leaving that

for our next model.

Suppose B is a butterfly collector who

has

travelled to the American Midwest to pursue his hobby; but, influenced

by A who is a geologist, B helps him

prospect for mineral

deposits. B is obviously not doing

what he originally wanted to do. A

may eventually establish a mineral chart of the area. B may

also succeed in interesting A in butterflies and make

him spend some time running after them.

Figure

4

The

more the vector of product p

approaches gA, the more we can say

that A has power over B and the

more p will accrue to A.

CONFLICTING POWER RELATIONSHIP

This

is what in game theory language corresponds to a zero‑sum game. It is

the

extreme of opposing interests. What A

wins, B loses, and is not willing to

lose.

The

likelihood that B will resist the

exertion of power by A will be great

and Aic may consist mainly

of threat directed at B. There will

also be a considerable amount of [B![]() ],

or a tendency to non‑compliance on the part of B, which

will have to be taken into

consideration in the evaluation of Bi’.

],

or a tendency to non‑compliance on the part of B, which

will have to be taken into

consideration in the evaluation of Bi’.

Figure

5

There

are, of course, variations to the conflicting situations. A and B may be after the

same indivisible goal and their clash may be competitive like that of

two

football teams. Or A may have designs

to dispossess B of some of its

sources of power, like two countries at war over a territorial dispute.

Our

earlier models can turn into or involve conflicting dimensions. This

may be the

case, for example in the commensal situation of landowner A

and farmer B, or their

parallel version of feudal‑vassal in the divergent model. If A goes for total submission of B in

order to expand his land, or if B exploits A's land

for quick profit

with a view to wresting it out of A's

hands, resulting in the erosion of the land, A

and B will clash in

their conflicting interests. For the symbiotic model the extreme of the

predator and the prey relationship turns, of course, into an obvious

conflict

of interests.[33]

In

the conflicting situation ‑ more than in other models ‑the

probability will exist that after a power confrontation there will

remain a

contestant to the product. The product accruing to A

may have been a former possession of B. Of course, the

outcome of the conflict may have been the total

annihilation of one of the contestants, or, total absorption of

one by the

other: The product may have been B

itself; an outcome which calls for a better understanding of the

product.

IV

THE NATURE OF THE PRODUCT

OF POWER RELATIONSHIPS

Figuratively

speaking, the chunk that A bites off B

should be digestible. The presentation pA indicated

the feedback of the

power relationship's product into A's

circuit. In absolute terms, not only should it be more substantial than

the

cost A has incurred (pA > ic), but it should be compatible with A's resources and other power

potentials. It should become part of A.

PRODUCT‑COST

REPLENISHMENT FUNCTIONS

The

problem that arises is that of the product‑cost replenishment

relationship. The product may indeed be more important than the

cost incurred,

but it may be alien to A's organism

or require a slow digestive process. Were the acquisition of the Grand

Duchy of

Warsaw by Russia at the Vienna Congress, or the occupation of

Yugoslavia by

Germany in World War II, desirable products of a power relationship? It

was

Bismarck's awareness of this problem which made him adopt a diplomacy

of peace

in Europe after the Franco‑Prussian War in order to let time work for

the

cohesive assimilation of the components in the newly born German Empire.[34]

There

may also exist a catch in the ratio between the cost and the product.

True, the

power relationship can be considered positive and rewarding for A when pA > ic.

But by how much? A power which uses a great quantity of its cognate

resources

to acquire a substantial quantity of an alien material may find its

cohesion and

composition weakened. To keep in line with previous examples, recall

the case

of the heterogeneous Austro‑Hungarian Empire and its fate.

Thus

in our potentio‑kinetic evaluation of power we have to take into

account:

(a) the compatibility of the nature of the product of a power

relationship with

the nature of the powers it will be absorbed by,[35]

and (b), depending on the consequences of (a), the ratio between the

cost and

the product. The measurement of this ratio is subject to the nature of

the

product for the obvious reason that the more the product is compatible

with the

nature of the receiving power the easier it can replenish the

cost. These two

dimensions imply (c) which would represent the rate of absorption of p into the potentials of the receiving

power and its rate of convertibility into kinetic power. This last

point also

covers the more general question of convertibility of the potential

resources

as a whole into kinetic energy: How readily liquid and ready to be

activated

are a power's potentials?[36]

POTENTIO‑KINETIC

CONVERTIBILITY

Beside

the product accruing to a power as a result of its transactions, its

own

cognate resources each have different degrees of convertibility. A

country may

have vast iron and coal resources, but may not have industrial and

manpower

capacities to turn those resources into machinery and weapons. What we

are

considering is the relationship between A

as the total power potential and Ai

as its kinetic action. Let us go back to Max Planck's stone on the

wall.

Standing atop the building, A can

threaten B underneath that he will

throw on him the massive stone if he does not comply with A's

command. The stone, according to the laws of gravity, has

indeed the potential of falling. But, if it were solidly and heavily

cemented

to the building, while we may calculate its potential according to

physical

laws by multiplying its weight and its distance from the ground, it

does not

constitute a power potential for A

because he can not turn it into kinetic power; and B, aware

of this fact, will not be impressed by his threat.[37]

Now, suppose the stone in question is not solidly cemented, that A has a lever at his disposal which

could topple the stone, and that B's possible

movements underneath are

limited. The potential fall of the stone is a threat to B if

he does not comply with A's

command.

In

this situation A's superiority over B is

his position and the means which he

can turn at will from potential into kinetic. A is

powerful because he can make B feel his threat,

making the latter comply with his demands

without having to topple the stone. As long as this situation prevails,

A keeps his power over B. What

if A did topple the stone?

The

moment the stone starts its free fall may seem the zenith of exertion

of power

by A over B. But it is also the

moment when A ceases to have control over the means of

its power. If the stone

does not hit B, the power of A over B will be exhausted. If the stone does hit and crush B, with the elimination of B the power

situation will altogether

cease to exist (assuming, of course, that A

was limited by the elements under consideration). The situation evokes

Mao

Zedong's famous thought to the effect that “political

power grows out of the barrel of a gun “[38]

which, in the light of our illustration, should be qualified by de

Madariaga's

lines: “The gun that does not shoot is

more eloquent than the gun that has to shoot and above all than the gun

which

has shot”.[39]

If A had a way of replacing the stone or

lifting it back before it hit B, we

would then need to reevaluate the different situations.

Now

suppose that next to B are C, D, E,...in situations similar to B, having

limited possibilities of

movement and threatened by toppling stones from A's

position (and A has

more stones ‑‑ President Reagan invaded Grenada and bombed Libya

and had more ships, planes and missiles). While the isolated power

relationship

between A and B will have ceased on

the crushing of B by A's stone, the

event

may now be added to A's power

potential in relation to C, D, E ...

n who, having witnessed the course of events,

will be more clear

about A's intentions. In this

hypothesis A may have lost one power

relationship but may have enhanced his reputation in relation to others.

Although

our examples may have helped illustrate the kinetic concept of power,

the

addition of just one more dimension will show the complexity of power

relationships and the difficulty to establish quantitative and

mechanical

patterns for them. Take, for example, a case in which the sight of B being crushed aroused A's religious

and moral convictions and

he renounced using his possibilities further. Not only will he no

longer be in

a power situation, but those under his control may ascend to his

position and

take over; that is, as soon as A's

new dispositions have shown exterior signs. The injection of religious

and

moral convictions into the equations of power, however, moves us

towards

restraints and constraints imposed on power by a value system

which, as we

shall discuss in chapter IX, if shared by those submitting to

power, could

serve for the legitimization of power into authority.

V

SOURCES OF POWER

Our discussion of the convertibility of potential power into kinetic has led us into yet other dimensions of our topic.[40] We are no longer talking about bricks and guns as sources of power, nor cement as a handicap to the use of power. We say that by throwing the first stone A could create a new dimension for his power ‑ his stone throwing reputation with C, D, E, ...n. But his crushing of B could also create religious remorse in him, in many ways a bigger handicap than the cement of the wall. Of course, the action could also have had an inverse effect and removed his inhibitions about killing. The control to which we referred earlier, which the child exercises through his charm to get the candy, is obviously not based on physical force but is already a more complex phenomenon containing the ingredients of power.

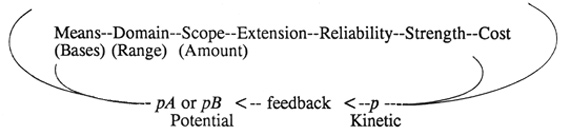

As pointed out earlier, we are making a distinction between power and the normative, legal and authoritative systems. At the same time we will include in this section some, and in the section on spheres of power other, hues of a spectrum which recent analyses of power have broadly established as follows [41]:

Means – Domain – Scope

–

Extension – Reliability – Strength – Cost

(Bases)

(Range) (Amount)

Incidentally, the reader will notice that what was attempted

so far was

a feed‑back process to link the two sides of this spectrum.

The dimensions of power need closer examination.

BRUTE

FORCE

Brute

force can, of course, give its holder the possibility of control. It

lasts as

long as it is forcefully superior. But its very simplicity and

directness makes

it vulnerable and breakable. Naked force can be easily evaluated and

analyzed.

It is like a piece of stone; it holds only by its weight and rigidity;

when it

hits other rigid phenomena weaker than itself, it breaks them; when it

encounters superior force, it breaks. It can only be a part of the more

complex

and flexible phenomenon of power and should not be confused with it.

We

need to add here a note on terminology -- Keeping in

mind endnote 8,

Chapter 1. In our dissection of power we are giving

strict connotations to terms which in a broader sense can each be used

as

synonyms of power. Furthermore, it should be kept in mind that terms

carry with

them cultural, linguistic and ideological biases. In linguistic terms,

some

languages provide more or less flexibility for dealing with the concept

of

power. For example, the French language distinguishes between puissance and pouvoir. The first

closer to force and strength but not quite

synonymous with them ‑‑ as the French language has also the term force. Puissance is a more palpable

concept of power.[42]

It is used,

for example, to identify foreign powers: les

puissances étrangères ‑‑ those powers whose presence

is felt at

the border. The term is also used for energy such as electric power. Pouvoir has a more complex connotation

and is more easily convoluted with authority.[43] Pouvoir – as

distinct from its Latin origin potestas – is both a noun and

a verb. It is a doing power. In German, Macht, which

stands for power, has a dynamic significance and is

related to action

through the verb machen. In English, Macht

turned into might and potestas and pouvoir turned into power. Both without a verb. Power is

not

something you can do; it is something to have and to be.[44]

In

our comparison of power and brute force, we could say that power has

the

potentialities of adaptation, resistance and pressure. In its encounter

with a

superior but simpler force it does not break, it can contract or

retreat and

withhold its potentialities without being irremediably crushed or

broken. When

in a favorable position, it can put on the rigidity of steel and give

its

adversary the fatal blow. It is the phenomenon which has retracted, yet

has

kept its potentialities and can make its pressure felt. The phenomenon

that has

been squeezed and takes its new squeezed shape without potentialities

of

pressure is not, in our analogy of power, a rubber ball or a spring. It

is a

piece of dough! Power is by its potentiokinetic presence.

Churchill, speaking

of the movements of the German battleship Tirpitz towards the P.O.

17 convoy

to Soviet Union in the Arctic in W.W.II, noted: “The

potential threat which they created had caused the scattering of

the convoy. Thus their mere presence in these waters had directly

contributed

to a remarkable success for them.”[45]

In

human terms, within the spectrum of brute force we can identify

physical force

(muscular) at one extreme, and certain aspects of stubbornness,

fanaticism and

determination ‑‑ individual or collective ‑‑ at the

other extreme. These latter intangible factors are included within the

concept

of brute force because when certain character traits such as

stubbornness or

fanaticism reach the point of rigidified behavioral patterns they

become

comparable to brute force. The propulsion they produce is forceful and

yet, in

its rigidity and directness, vulnerable and breakable.

Take,

for example, the character traits of Ayatollah Khomeyni of Iran in the

1980's.

In the Iran‑Iraq war of 1980‑1988, with dogged stubbornness he

mobilized his fanatical troops to withstand the shock of Iraqi attack.

Yet,

when there came the opportunity in July 1987 – when Iran had the

upper hand

and Saddam Hussein had accepted the United Nations cease‑fire

resolution

– Khomeyni was not flexible enough to take advantage of it. While the

situation

involved more complex power components which we shall develop later,

the case

in point here is that Khomeyni's vengeful stubbornness was a

factor in the

continuation of the fighting to the detriment of Iran.

Of

course, as it is for other sources of power, the evaluation of

brute force is

subjective and its outcome relative. .Within the power complex, the

assumption

is that if B submits to A's forcible

command it is because B finds submitting to A more agreeable than the consequences

of A's coercive punishment. The

assumption is subject to B's perception

of pain and pleasure and his relationship with A. A

masochist perceives pain differently from a paranoid.

MEANS

The

means at a power's disposal are obviously of great importance. By means

we

refer to a spectrum extending from primary tools and weapons, which are

nearer

to the force end of the spectrum such as a stick, to more subtle means

such as

money and wealth. We are using the term "means" in its stricter sense

‑‑ close to its material and instrumental characteristics.[46] The term "means" can, of course,

be given a broad connotation, particularly in the combination of

means and

ends, as done, for example, by Hobbes, mentioned earlier.[47] In that context, some have even gone so far

as to emphasize the preponderance of means over the ends. In the words

of

Gandhi: "They say 'means are after

all means'. I would say 'means are after all everything'. As the means

so the

end. There is no wall of separation between means and end. Indeed the

Creator

has given us control (and that, too, very limited) over means, none

over the

end. Realization of the goal is in exact proportion to that of the

means. This

is a proposition that admits of no exception"..[48] It is, of course, a question of semantics

and what we want the term to cover. Gandhi is using the term "means"

in a much broader sense than our meaning. As we noted in our discussion

of

force in the last section, terms can be given different connotations.

In the

broader sense, means can be used as a synonym for power; in particular

when

coupled with ends. What Gandhi says is that one needs power to achieve

one's

goals.

When

used in that broader sense, the coupling of means and ends raises

significant

philosophical debate in different cultural and ideological contexts.

The

question becomes that of the justification of power's

arbitrariness on its

course to attain a given goal. Such are, for example, the exercises of

power by

revolutionary regimes. That the doings of power have to be justified

implies

the presence of a value system to which the power claims or wishes to

adhere.

Thus, the dictatorship of the proletariat, whose goal is the

emancipation of

the workers and the establishment of human rights, may exploit the

workers and

oppress the people on its way to achieve the ultimate goal. Of course,

a power

which does not submit to a value system and does not aspire to

justification and

legitimized recognition is free from the means/ends constraints.[49]

Our

narrower usage of the term "means" here – limiting its connotation

to instrumental and material sources of power -- permits us to

dissect the

components of power more closely and better analyze their areas of

overlap.

POSITION

The

position from which power is exercised is another crucial factor. The

illustration given earlier of A atop

the wall is at the primitive end of the spectrum. Let us use that

example here

to make a first assessment of the three different components singled

out so

far. A was in a favorable position

atop the wall, his means were the stone and the lever, and he should

have had

the force to move them. As in the case of force and means, position can

cover a

spectrum going from the simple instance of a strategically favorable

location

to complex social situations.[50] The

president of a bank, the governor of a

state, the justice of the peace, each holds a position conducive to

power.

However, the aspect of the position we are considering here is not

totally

identical with what in those titles coincides with authority. What

we are

presently considering is neither an office, nor exactly the right to

the power

that it legitimizes.[51]

It is the power potential that a position can provide beyond the

framework of

its formal authority. Chamberlin, Churchill, Macmillan, and

Thatcher were all

British Prime Ministers. Of course, they exercised their authority

under

different circumstances and conjunctures. But it would be

unreasonable to deny

that, abstraction made of the circumstances and conjunctures, the kind

and

quality of the power each wielded was different.

A

bank president has the authority to sign the grant of loans. But he

does that

mostly on the advice of his experts. In performing that function

he may not be

doing more than a post office clerk who has the authority to notarize

signatures. Beyond that simple signature, however, the bank president

holds a

position which can radiate power. That depends very much on the person

and the

use he makes of the other sources at his disposal to wield power by

exploiting

his position. The bank president who exercises his duties strictly for

the

management of the bank and does not have a power base – inside and

outside the bank

‑‑ which inclines him to favor one direction as distinct from

another, is not using his position for those particular power ends.

Indeed, if

he does not, he may not last long in his position unless he is there to

buffer

contending powers.

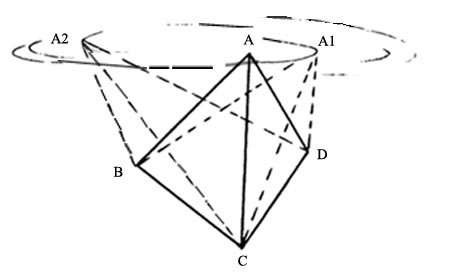

CONNECTION

This

dynamic concept of position leads us to further sources of power. A

power may

tap its connections with other powers ‑ not only vertically, but also

laterally and diagonally to strengthen its own resources. Power A may call on power C for help in the A/B power relationship and return help

to C in another context. The lateral

connection between powers in the fluid area between their

complexes implies

that they perceive mutual benefit and compatibility and convergence in

their

interests as compared to other combinations: ![]() The imperative of

connection leads powers to networking. In our earlier

classification of power

relationships we did not include a convergent power relationship.

Because

convergence, to the extent that it is lateral connection, while

creating a

"relationship", does not necessarily create a "power

relationship". As the fluid area between power complexes that have

lateral

connections is filled by their respective expansions, the lateral

connections

may evolve into diagonal relationships which could be symbiotic or

commensal

and eventually turn into a hierarchy. In that sense connection and

contact

are, as we shall see later, sine qua non components

of power which, besides being relational, is also hierarchical.

The imperative of

connection leads powers to networking. In our earlier

classification of power

relationships we did not include a convergent power relationship.

Because

convergence, to the extent that it is lateral connection, while

creating a

"relationship", does not necessarily create a "power

relationship". As the fluid area between power complexes that have

lateral

connections is filled by their respective expansions, the lateral

connections

may evolve into diagonal relationships which could be symbiotic or

commensal

and eventually turn into a hierarchy. In that sense connection and

contact

are, as we shall see later, sine qua non components

of power which, besides being relational, is also hierarchical.

According

to Parsons, "While the structure of

economic power is... lineally quantitative, simply a matter of more

and less,

that of political power is hierarchical; that is, of higher and

lower levels.

The greater power is power over the lesser, not merely more

power than the lesser. "[52] Of course, this qualification implies

comparability.

Without relationship and connection, it is not realistic to compare the

power

of a Soviet farm cooperative manager in Siberia with those of the

Sheikh of Ras

el Kheyma, a banker in London or a Medellin drug baron. Even where

indirect

relations exist but direct connections have not been established, one

relational situation may not imply another. For instance, it does not

necessarily follow that because A is

more powerful than B, and B is more

powerful than C, A

is more powerful that C. The nature

of the relationships may not be comparable, and as long as they are not

connected in a power relationship ‑‑ whether by the intermediary of B or otherwise ‑‑ we

cannot say that A has power over C.

The AB relationship may, for example, be professional,

while the B/C relationship may be paternal or

conjugal.

The

assumption, however, is that where power relations exist, hierarchical

imperatives arise. Even the lateral mutual help connection will not

always

remain on a par and will be subject to the interplay of the whole

potentials of

the components.

POWER

OF PERSUASION AND INFLUENCE

Carrying on with

connection, to

secure C's cooperation, A may need to

persuade C that the product of their mutual

assistance will benefit both of them. If A

has a good power of persuasion he may draw a picture showing all the

advantages

to C, although, in fact, in the long

run the outcome may be more profitable to A.

This eventuality brings us to the power of persuasion as yet another

source of

power. Persuading B to do i' in a

vertical power relationship is

also one of the possibilities for A

instead of using his force or material means. Depending on its

magnitude,

sphere and duration, persuasion could serve as one of the factors for

the

legitimization of power into authority, which we shall discuss later.

To

persuade implies the capacity to influence or to have influence. Of

course, the

simple fact of having influence may not involve a power relationship.

To

illustrate our point, suppose you told your friend in a restaurant that

a

certain stock was likely to rise on the market, and someone next to

your table

overheard your conversation and as a result bought that stock ‑‑

something he would not have done otherwise. You have influenced him but

you

have not consciously exerted power upon him. Like other ingredients of

power,

only that part of influence which connects effectively will be part of

a power

complex.

Note

our specification of influence as one of the ingredients of power

and distinct

from it.[53]

The gradation from "having an influence on”[54] to "having control over"[55]

can be established in the potentio‑kinetic sense. The effect of A's action on B may be the creation of

a disposition, or rather predisposition,

for a changed behavior in the future.[56] B

may not have complied the first time, but if he did the next time it

may be

because the leftover of A's last

influence magnified the influence exerted upon him this time. That is, B would not have complied with A's

desire or command this time if the

last event had not taken place.

We

may equally conceive of situations where the earlier influence may have

an

adverse effect on attempts at later control. Take for instance the

guilt

complex inculcated by the parents into a child against stealing and

that

child's inhibition to do so when asked by his parents in a desperate

survival

situation. We can extend that analogy to the consequences of unfair

treatment

of an adversary's population in a conflict by a nation upholding

humanitarian

principles ‑‑ the case in point is the public and media outcry in

the United States against the use of "Agent Orange" in Vietnam.

The

potentio‑kinetic concept implies, of course, that the earlier influence

and later control should be part of a continuum within a given power

complex.

If gang‑leader A's threats do not induce member B to

obey but create enough predisposition in him to obey later as

a soldier faced with a superior threat from sergeant C, B's

obedience to C should not be counted as the power of A over B.

B's inner disposition,

however, is a

factor that should be taken into account. We are thus recognizing the

inner and

outer properties of certain sources of power. It is in the

fermentations and

dynamics of the power complex that the internal properties of its

components

become effective. The external manifestations, however, become part of

the

power complex insofar as they correspond to an inner reality. That

reality may

or may not correspond to the external manifestations, i. e., looking

tough and

in reality being tough or, as we shall see later, being aware of its

own

exterior manifestations by the entity emitting it.

SELF‑CONFIDENCE,

CHARISMA AND REPUTATION

The influence exerted

on the eavesdropper in our earlier example in the restaurant may have

been due

to a confident tone. In other words, the apparent self‑confidence of

the

person making the statement. Here we are speaking of the external

appearance of

self‑confidence which may involve no power control. In a power

continuum,

as mentioned above, it should be coupled with consciousness.

In the long run, apparent self‑confidence

can remain a component of power if it reflects inner self‑confidence

and

to the extent the person emitting it is conscious of it. This

latter

prerequisite has a reality of its own independent of the former; i.e.,

a person

who has little inner self‑confidence may be conscious of the fact that

because

of some elements of his exterior appearance and personality, such as

charisma,

he radiates self‑confidence, or he may discover that certain behaviors

or

attitudes indicate self‑confidence and may adopt them. These are, of

course, components of consciousness which we shall deal with shortly.

Here,

however, the point should be made that "acting" self‑confident

develops into a tool for attaining other components of power: For

example, in

certain contexts – such as is often the case in the United States – one

of the

crucial criteria in the selection of decision‑makers is the

demonstration

of the capacity to make quick decisions. When a decision is called for,

the

clever aspirant to power takes the initiative of taking the decision –

whether

he has sufficient reasons for doing it or not ‑‑ and distinguishes

himself as a leader and a quick decision‑maker. Keeping ahead of his

mistakes – where he has erred – he may thus advance on the social

ladder and

acquire other sources of power.

Apparent

self‑confidence can thus be counted as a source of power. Its impact

becomes evident when it is combined with other ingredients: force,

means and

position used with selfconfidence; and self‑confidence as a

dimension of

influence and the persuasive process. Charisma, mentioned in that

context, may

be a characteristic in its own right. But it is seldom separable from

the power

of persuasion and self‑confidence. It may, of course, happen that a

charismatic person is not necessarily self‑confident, or that he

inspires

rather than persuades.

Back

in the restaurant, we may find that the eavesdropper is influenced

by the

speaker's reputation. He may be influenced even by the reputation of

the

restaurant! Suppose he is an amateur investor having lunch in a

restaurant near

Wall Street known for being the rendez‑vous of financial experts.

Taking

his neighbor at the next table, who behaves like a habitu6 of the

restaurant,

for a stock exchange expert he may be impressed by what he overhears

and act

upon it.

Reputation

can be produced by other components of power. Consider the

possibilities of

combining means (money and mass media) with persuasive techniques

(contents of

mass media programs based on social psychology) and through publicity

and

propaganda creating a given power image. Reputation, however, implies a

time‑space

continuum. In just about all human cultures, and even among some

animals,[57]

pedigree can serve as a source of power. It is the reputation the

holder has

inherited that produces the image. Where the name is known, a

Rothschild is

assumed rich until proven otherwise.

But

above all, reputation is

the manifestation of the potentio‑kinetic nature of power. It is a

present dimension of power, based on the experience of its past

behavior, plus

the potentials available to it for future action. The hords of

Jenghiz Khan

became invincible as their reputation preceded them.

CONSCIOUSNESS

AND

WILL

In

the human context, all this, of course, implies knowledge and

know‑how which, beyond implying specialized

skills, should include the general

capacity to analyze, to evaluate, and to draw appropriate conclusions

for

action ‑ including timing, improvisation as well as organization and

planning.[58] It is this capacity that can establish

the relative value of the components of power, even the intangible ones

such as

self‑confidence and reputation. A power can combine and exploit

its

potentials to extents which may exceed the possibilities of any one of

the

components in isolation. Its potentials include its awareness of

external

manifestations of its properties not corresponding to its inner

realities, and

its capacity to use them, in other words, bluff.

Courage and risk‑taking are

components of power. In its analysis of possibilities, a power should

relate

its power position to other power complexes in the context of

total

environment. When Churchill asked his chiefs of staff on British

preparedness

to face the Germans, they replied:

"Our

conclusion is that prima facie Germany has most of the cards;

but the

real test is whether the morale of our fighting personnel and civil

population

will counterbalance the numerical and material advantages which Germany

enjoys.

We believe it will.”[59]

Later events proved

them right.

The

knowledge factor is so important that it has become the subject of

simplification for those who are in search of power but are incapable

of

essentially absorbing it. Knowledge has thus been reduced to

information.

"Information is power," so the saying goes. But information is only a

tool of power which enhances power insofar as a power knows how to

use it.

Francis Bacon, that old hand at using different variations of power,

had said nam et ipsa scientia potestas est.[60] Information is a most important tool for

power. But if the capacity to use it is not present, information will

be a

computer ticking in the desert.

Power

does not imply that the powerful "possesses" all the sources of

power. Knowledge means knowledge about the availability of the sources

of power

and the capacity of combining and using them. Where A

wants B to do something

that it would not have otherwise done, and where C has

strong and agile muscles and D has a club, A can exert

power over B if it persuades D to

give the club to C and C to hold the

club over B's head

so that the latter complies with the wishes of A. A, for all that matters, may

be a midget.

The

analytical and evaluative capacities of a power then cover not only the

consideration of its own relationship with another power, but also the

analysis

and evaluation of the conflicting natures of other powers or simply

different

textures and shades of those powers in their relationships. Thus one

power

complex may use other powers against each other or combine some of them

against

some others in situations beneficial to itself. Great Britain remained

a great

power through the 18th and 19th centuries partly because she

successfully

played this balancing game in the European power complex.[61]

Parenthetically

it should be emphasized that while cognition, consciousness, will,

knowledge

and the capacity to manipulate information have been enumerated as

components

of power, wisdom and sagacity have not been included as its sine

qua non characteristics. While

intelligence and cognitive elements of wisdom can be used for power

ends,

wisdom and sagacity in themselves may not aspire to power. Indeed,

history is

fraught with powerful wisdom midgets.

Our

parenthetical remark leads us to two "factors" of social power,

namely, competition and ambition. They

are not sources of power

but rather propulsing factors for the realization of power. They are

social

manifestations of the will to power and domination drive discussed

earlier and

account for the existence of powerful wisdom midgets. History is

lamentably

short of philosopher kings. What it is rich in are ambitious, shrewd

operators

manipulating the sources of power to get on top of the heap; modelling

themselves after The Prince of

Machiavelli rather than taking inspiration from the Meditations

of Marcus Aurelius. These

factors translate into such social theories as the

survival of the

fittest, and the selfish interest motives of capitalism, and are social

realities reflected in processes of legitimization of power into

authority

which we shall touch upon later. In the democratic process, for

example, the

operators get the money from the rich (notably through contributions to

the

candidate's party or campaign funds), use it to impress the people

through the

media, get support through a give‑and‑take network of other

operators and potential cronies, and finally the votes of the

multitude. They

then project an image of wit and intelligence by employing

speech‑writers

and devise their strategies and policies by picking the brains of the

intellectuals. In different systems it turns into the manipulation of

the

apparatus by operators and apparatchiks, producing

representatives, senators

and presidents. Of course, what interests us more here is their will to

power

and their consciousness about the ways to get it rather than the

authority attributes

of their position.[62]

The

relationship between the will to power and the ways for its attainment

is

crucial for the understanding of the entelechy of power. The saying:

"Where there is a will, there is a way" is true insofar as the two

propositions are connected, i.e., the

person who wills power knows the way and engages in it. The case which

best

illustrates our point is probably that of Nietzsche, the philosopher

of the "will to power".[63] Conscious

and cognizant of his own will to