Epilogue

The future of man

remains undetermined because it depends on him.

Henri Bergson

We propose here to

take three critical steps back,

through institutions, which we have been discussing most recently, and

authority, which we dealt with before that, to the individual. We shall

see

that as we take these steps, we sink in turgescence, redundance and

hypocrisy,

which reveal human realities beyond either biological or philosophical

circumscriptions. Our discussion is not intended to be a summation of

what the

book has covered, but some afterthoughts on the nature of the phenomena

considered.

I. Institutional

Turgescence

In the context of the

total environment, men and their

social, and political institutions should make sense, not necessarily

in any

ultimate terms, but at least in relation to each other. However, these

relationships‑‑and this must be emphasized‑‑take place

in the context of the total environment. When we observe, for example,

the

existence of an institution, we may infer a corresponding need. On

closer

examination we may find that the institution does not correspond to the

need,

or that the need does not exist. But that is only because we have

looked

closely‑‑too closely, perhaps, If we broaden our perspective, we

may find that while, according to certain rationale, the institution in

question may not correspond to a given need, we can nevertheless

explain its

existence. In an underdeveloped country a few years ago, I visited a

village

which had traffic lights but practically no motor vehicle traffic. The

institution obviously did not have a corresponding need, That is true,

however,

only if we forget the human element. There were traffic lights in the

otherwise

underdeveloped village because, in the first place, the region had an

excess of

electricity due to the construction of a new dam and because traffic

lights, if

they did not serve as useful signs,

at least served as symbols of

progress, modernity and therefore prestige. Of course, in general, we

are

probably more likely to find intersections that need traffic lights but

don't

have them, or traffic lights that are not properly synchronized and

thus

contribute to traffic jams rather than alleviate them. The example of

the

traffic light is rather simplistic. The point is that institutions do

not

always correspond to needs in the social‑rationale sense.

By institutions we

mean any aspect of cognizable social

and political structures ‑‑ whether moral, ethical or legal norms,

or constituted bodies such as an association or an office. Our earlier

causal

assumption that an institution implied a need for it was itself

indicative of

the need/institution lag. It

implied that in human terms an

institution is created to fulfill a need, which further implied the

likelihood

that the need preceded the institution. This is plausible considering

man's

attributes as a thinking animal whose institutions do not result simply

from

spontaneous and automatic instincts. He may create institutions in

anticipation

of future needs; but they will not necessarily correspond to needs once

they

arise; for while man can predict, he

cannot know the future in the

complexity of the total environment. The mention of the total

environment

should remind us again that it is not enough to explain the

need/institution

lag on the basis of rational rationales but also in the light of human,

and not

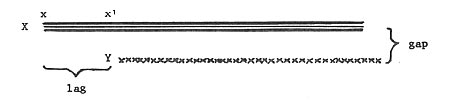

always so rational, factors. Need X may

arise at point x. Not only will

institution Y not come about

spontaneously, but it may not even be provided at point x'

when the need for it has been identified. Depending on the

circumstances, institution Y may

never be created.

Fig. E‑01

There may be other

priorities pre‑empting the

provision of institution Y for need X.

That is, the need for the institution

may be felt by those who need it, but not recognized by those who

establish the

institutions.

By the same token,

because of the discrepancy between

those in need and the institution‑makers, even when an institution is

created to meet a particular need, a gap

will exist between the intrinsic need factor and its extrinsic

evaluation and

satisfaction by the institution. Here, of course, we are implying all

the

complexities covered throughout the book, such as the degree of

participation

and control which those who need an institution have in creating and

running

it. The more those who run the institution coincide with those who need

it and

the more they are controllable and accountable for the utility and

efficiency

of the institutions, the smaller the gap between the need and the

institution. But

in human terms, it is hard to conceive that they will totally coincide.

Indeed,

if they did they would consummate each other,

and the need/institution constellation would hardly be

recognizable. So,

even if institution Y were created to

satisfy need X at point x' when the

need for the institution was

identified, Y should not be presented

as superimposed on the trend of X,

but placed at a gap with it. The gap will be wider or narrower,

depending on

the coincidence of the identity and understanding of those in need and

those in

charge of the institution.

Fig. E‑02

But a gap, no matter

how narrow, will always exist. Even

an individual does not always provide means ‑‑ even when he can and

is consciously aware of them -‑ to satisfy his own needs. The social

need/institution gap can, of course, increase or decrease where there

are

deviations and adaptations ‑‑ which may be mutual, because needs

can also be conditioned by existing institutions. Also, it is possible

that

those instrumental in creating an institution may cause it to cease

functioning

before the need has been met, in which case there will again be a lag

further

along the need/institution combination representing an unsatisfied

need. This

last hypothesis, however, demands another reminder of human and social

conditions. A partially satisfied need is harder to suppress than one

that has

not been acknowledged at all, because a human institution is not like

running

water or electricity that can readily be turned on and off. Beyond its

implication that those whose needs the institution served will be more

consciously dissatisfied, the phenomenon leads us, in our broad

perspective, to

another human dimension central to our present inquiry.

By virtue of their

human factors, human institutions are

not simply organic and mechanical. A human institution not only serves

a social

purpose and a need, but is at the same time an instrument for those who

control

it, and a source of livelihood for those who maintain it. An

institution,

therefore, evolves not only according to the social need for which it

is

supposed to have been created, but also under the influence of its

controllers

and occupants.

It is understandable

that those who control an

institution cherish it as a base of their power, and it is equally

understandable

that those whose livelihood depends on the institution also want to

perpetuate

it. While the evolution of an institution for such reasons can be

explained

within the rationale of the total environment, it is not always easily

justifiable within the narrower relational rationale of the original

social

need which it was presumably created to satisfy. We may call the lag

resulting

from that evolution institutional

turgescence. Not only may it cause

the institutional trend to deviate from that of the need, but it may

also

perpetuate the institution beyond the need. For example, those who

control the

institution ‑‑ at different levels of responsibility ‑‑

will probably try to consolidate the base of their power by populating

the

institution with their own types, a trend that can result in

favoritism,

nepotism and the spoils system. Institutional turgescence is also

reflected in

the bureaucratic propensity to create busywork, redtape and extra

positions to

handle it, expanding the institution into a self‑perpetuating and

self‑propelling

body. Parkinson's Law did not gain renown as a satire because it was

merely

amusing, but because it depicted a human reality ‑‑ and not a new

one. Chaucer, six centuries earlier,

had said of his Sergent of the Law:

Nowhere

was there a man as busy

as he‑

And yet

he seemed busier than he

was.

Institutional

turgescence develops more easily when the

institution is fed funds indirectly so that the connection between the

funds

invested and the institution's corresponding accomplishments are

blurred, and

when there are fewer checks and balances, whether directly by those

whose

social needs the institution serves or by other institutions. The

citizen is

more likely to notice his mayor using for private ends the limousine

bought

with public money for official business than he is to notice his

country's

ambassadors in other lands doing

so.

For purposes of

analyzing a polity's efficacy, we can

establish an institutional turgescence scale. Where the lag between the

emergence of needs, their recognition, and the creation of institutions

to

satisfy them is short; where the gap between needs and institutions

remains

narrow; and where the lag between the passing away of a need and the

dismantling of the corresponding institution is short, the polity may

be

considered harmonious and stable, with small zones of conflict and

dissatisfaction. Where these conditions are reversed the likelihood of

conflict

increases. Whether the greater zones of conflict between the needs and

institutions will cause the polity to collapse depends on the

consciousness of

those involved. For those in the institutional oligarchy, the situation

may

sometimes look more and more like it is working because they have shut

out

their critical vision. Yet the situation may continue if those in need

are

resigned to the prevailing order. In other words,

there are psychological factors involved which could either

help perpetuate the establishment or precipitate change.

II. Authority

Redundance

When in Chapter Two we

defined liberty as a sociological

need, we used an elementary proposition to explain that, abstractly

speaking,

man lives in groups because, all considered, they are better than the

state of

nature. Formally, the proposition could read: GB > SN (i.e., Group Benefits

are greater than what man can get in the State of Nature). We have long established that because man is a

political

animal, the state of nature has never been a human reality. But even

though man

is caught in his social dimension, he dreams of and visualizes a

wilderness

where he could speak his mind to the authorities who push him around.

This idea

was reflected in some of our topics, such as those dealing with man's

adventurer inclinations and with anti‑norms. Now, with all the

complexities we have behind us, let us use our simple formula in a

simple

hypothesis of polity development to see whether there is any inherent

human

phenomenon keeping institutions from corresponding totally to social

needs.

By "group," we said,

we did not mean a cluster

of units confining each other but interacting with one another. To put

it more

concretely, in a small communal setting, Mr. Jones, wanting to contact

Mr.

Smith ‑‑ to go to his farm, for example ‑‑ would have

to go through Mr. Doe's domain – Doe’s place of sustenance and rest.

This

intrusion of Doe's domain ‑‑ his liberty ‑‑ is, part of

the price he pays for the benefits he draws from the group. In fact,

Jones'

passing through may be no intrusion at all. Doe may enjoy having the

chance to

chat with Jones. That can be part of the group benefits. If, however,

the group

grows so that more and more people whom Doe knows less and less keep

passing

through his domain, it might become a nuisance for him and for others

who

submit to the same interference. The practice could, in effect,

establish a

right of passage through their domains and thus infringe on their

rights,

giving rise to the need for a public road.

We can, of course,

conceive of an already existing

authority to take charge of satisfying this need. But to make our point

step by

step, let us assume that to take care of the need for a public road,

the

members of the group join to establish a particular authority. First,

of

course, they have to decide where the road should be, which may imply

that some

have to cede their land and that others have to compensate them. We are

slowly

moving beyond the informal group benefits toward more explicit and

formal

public interests, which call for further concessions by individual

members of

the group, including remuneration for the authority established to

build roads.

In our hypothesis of the individual's conscious participation in group

life and

his hypothetical alternative, the state of nature, we should now add

the new

dimension of public interests to our

formula. The sum total of the group benefits and the advantages to be

drawn

from public interests (PuI) should be

greater than the concessions one makes on his hypothetical absolute

freedom of

action in the state of nature. Thus:

|GB + PuI| > SN.

Of course, public

interests refer not only to a single

situation such as constructing a means of communication. Any society

beyond an

isolated primeval level develops social needs for intercourse and

exchange

requiring structures and rules, i.e., institutions and laws. Beyond a

certain

group size, authority cannot be exercised by the whole aggregate of

individual

members and will have to be vested in some body (individual or

institution)

responsible for organizing the institutions which serve public

interests. It

will speak in the name of the group which has instituted it. Let us

designate

this authority as A. A

will become the concrete representation of the abstract "group," a

point of reference for both its individual members and those who serve

the

group.

If, in our example of

road‑building, someone finds

the road not properly constructed, he will complain to A.

In like manner the contractor building the road, recognizing A as the job‑giver, will heed his

instructions and pay him due respect. The concentration of the group's

"will"

in authority A and the exercise of

his assigned functions thus acquire for A

a certain amount of prestige and an aura of superiority by which he may

be

advantaged and on which he may draw beyond the quid pro

quo remuneration of his services. The road contractor may

do a better job around A's property

for which, in the long run, the other members of the society will pay.

The city

mayor may receive more respect and consideration from the police corps

than

does the common citizen. Try to tell the tax collector or the policeman

that

you contribute to his upkeep and that he is really your servant; you

will be in

trouble! The president of the republic is honored: traffic is stopped

for him

and he is accompanied by a motorcade.

As authority becomes

more complex, some of these

additional attributes which do not directly contribute to public

interests are

conceded by the members of the group, and others are taken, or taken

for

granted, by the authority. While the remuneration A receives

for his

services may be considered an expense incurred for the sake of public

interest,

the surplus attributes he accumulates because of his position entail no

returns

for the group members, who put up with them as necessary evils for the

sake of

the GB and the PuI. In our formula,

it should be deducted from their total. Let us

call these surplus attributes Authority

Redundance (AR):

|GB + PuI ‑ AR|> SN.

Authority redundance

cannot be calculated objectively. It

is a psychological factor and, in the final analysis, depends on what

the

individual considers redundant. Some authority attributes may engender

affectional satisfactions, such as national pride in a coronation, a

military

parade or a monument. They cannot altogether be considered authority

redundance, for they contribute to group benefits and public interests

by

nurturing such strongholds as nationalism and cultural identity, which

provide

group cohesion.

Up to now our formula

has confined the individual's side

to the hypothetical state of nature alternative. We pointed out earlier

that,

while the individual may indulge in weighing the advantages of social

life

against those of the state of nature, the state of nature is only a

point of

reference, like the North Star for navigators, and not a state the

individual

can attain totally. As the formula now stands, group life is a

take‑it‑or‑leave‑it

proposition for the individual, with the "leave‑it" side only

hypothetical. But this situation would reduce the individual to

servitude. In

the extreme he would be a slave in chains. Beyond that extreme,

however, social

dynamics assume an exchange between the two sides of the formula. The

state‑of‑nature

freedom, which the individual relinquishes and which turns into group

benefits,

public interests and authority redundance on the other side of the

formula, is

the raw material on which the group draws, but which also, as

individual

liberty, emanates from the group as a whole, of which the individual is

a part.

Thus he can aspire to share in the social part of the formula. In other

words,

the individual has some potential power (PP)

which, socially speaking, he can at

some stage convert into social action. The more the conversion of

potential

power is fluid, the more the individual not only enjoys the fruits of

group and

public action, but also partakes in shaping them, and consequently either shares authority

redundance or neutralizes it. We may now realize that when the

conversion of

this potential power of the individual to the |GB + PuI – AR| side is handicapped, his

alternative

is not reduced to the hypothetical abandonment of social life,

reverting to the

state of nature. His potential power may turn instead into Militancy

Potentials (MP)

within the social context to resist and fight what may have become an

unacceptable amount of authority redundance. Our formula will then read:

|GB + PuI – AR| > |SN + MP|

←PP---

The establishment

maintains itself best where the members

of the society, like Voltaire's Candide, believe that "all is well in

the

best of all possible worlds." This situation does not necessarily imply

the greatest social consensus, public service, flexibility and mobility

among

the social strata, but may imply high degrees of conformity, strict

socialization, persuasion and indoctrination, as discussed earlier. The

harmonious

consensual situation is, of course, one where maximum group benefits

and public

advantages are enjoyed by the members of society, where authorities do

not

abuse their positions, and where the process for converting individual

potentials into social benefits is adequate. These advantages need not

all be

present for the establishment to survive. For example, while some

members may

consider that at a given time the advantages offered by the

establishment are

not satisfactory and the authority's abuse of power is excessive, they

will not

necessarily use their militancy potentials to overthrow the

establishment, but

may rely on the future conversion of their potential power to replace

the

established authority. Such would be the case of an opposition

political party

in a polity that provides for an honest electoral process.

Our conceptual

formulation should therefore be understood

as a temporal continuum, and our power potentials as those potentials

which,

under the existing social order, are convertible at a future time.

Potentials

converted immediately become militancy potentials, amounting to a

revolt

against the establishment. The student who disagrees with the

educational

system as provided by the establishment may yet submit to it because it

offers him

possibilities to play a role in the establishment in the future. After

he has

obtained his degree, whatever social benefits he draws from it will be

transferred to his social side of the formula, and he will rethink his

formula

in the light of his new position and power potentials. The student who

does not

believe the system is worthwhile may revolt, either by violence or by

alienation, by joining a militant body or a commune. The final outcome

of this

on the social structure will depend on the dynamics of the dissatisfied

elements and their impact.

A situation is, of

course, conceivable in which the

establishment side of the formula is negative and yet the establishment

maintains itself. This would correspond to a despotic police state

where

authority redundance exceeds the benefits offered to the members of the

society. Authority redundance includes not only the money the dictator

spends

on his limousines, but also the police force he maintains which does

not

safeguard the members of society but persecutes them, puts them in jail

and

encroaches on their liberties. Somoza’s crushing of the uprising in

Nicaragua

in 1978 was a classic example. In such a

situation, AR > |SN + MP|;

i.e., the individuals or groups submit to the establishment, although

resenting

it, because they have too few liberties and militancy potentials to

reverse the

trend of authority redundance. If and when the trend can be reversed

and a

successful attempt is made, it will be revolutionary instead of the

previously

discussed evolutionary conversion of

power potentials. Anarchy, in the popular sense of nonexistence

of government and consequent confusion

and disorganization, may accompany the moment of passage when AR = |SN + MP|, and may

last

longer where the SN factor within the

emerging powers is greater, or shorter where the MP

prevails (militancy also implying discipline). As with the

revolution the potentials materialize into the establishment, the

members of

society will become entangled in the new social network with its new

authority

redundance. The subjective evaluation of social realities by

individuals,

whether those who constitute (or feel they constitute) the

establishment or

those who submit to it, and their corresponding behavior and actions

are then

the raw material of political authority. Thus, after our brief and

critical

second look at institutions and authority, our final step takes us back

to the

individual human behavior with which we began.

III. The

Ideal/Real/Hypocritical Loop

At the beginning of

this book we said that political

science was the science of truth. We know, however, that truth is

relative,

depending very much on what an individual believes to be true. To the

extent

that he acts thereupon, his truth becomes the convictional support for

his

action. Truth, however, is relative not only to the individual but also

to his

total environment. In the social context, truth according to a man's

belief and

the actual social phenomena is hard to perceive and to establish. The

possible

range for an individual oscillates between two extremes: the ideal and the hypocritical.

He may base

his truth on abstract values, and his "untruth" on his selfish

interests; i.e., he may be an idealist in the application of his truth

to his

social realities, or be a hypocrite in their evaluation for his

personal needs.

In the latter case, his values are false values, as elaborated earlier.

Politics is said to be

the art of the possible because it

requires consciousness of the critical

limits of social realities between the ideal and hypocritical extremes.

Politics is an art, however, not only because it requires consciousness

of the

limits and the extremes, but also because it calls for courage and

potentials

for probing those limits yet not falling into the extremes. Indeed, it

is critically

probing the limits that gives the political practitioner or scientist

the broad

perspective he needs of the social realities he is to cope with. The

political

practitioner or scientist who confines himself to the strictly material

and

concrete factors of social reality narrows his angle of vision. By

approaching

the ideal limits of social realities, he will enlarge his vision and

understanding of the "valuational" improvements that are

possible within the social context

he deals with. But he can do so only by moving, on the other side, to

the brink

of hypocrisy within the social realities in order to know the real

stuff of the

society, the visceral contents of the man he is dealing with.

You will see now why

the real art of politics is so

difficult to master, for it is very difficult to understand the

possible limits

of the ideal without becoming an impractical idealist, and it is

equally

difficult to use one's power to the limits of the hypocritical in order

to

understand the egoistic interests of others, and to promote one's

political

cause for social good, without

falling into the excesses of self‑indulgence. While by probing the ideal and the hypocritical limits of

social realities critically the political practitioner or scientist

broadens

his angle of vision, at the two extremes he also risks to sink into the

ideal

nebula or the hypocritical viscera. That could narrow his angle of

vision until

he is totally submerged. He may then become vulnerable, taking his

ideal or

hypocritical vision as real, and may indeed take one for the other to

justify

and balance, consciously or unconsciously, his behavior and action

within the

social environment. By rationalizing instead of being rational, he

would make

the two extremes meet and thus produce for himself an

ideal/real/hypocritical

loop where the ideal/hypocritical side mirrors the real, as the

negative

mirrors the photograph.

Within that loop,

hypocritical actions may be justified

by ideal abstractions, and selfish interests may wear a mask of

altruism. In

the name of civilization the British massacred the Mau Mau and the

French

tried to suppress the Algerian uprising; in the name of

anti‑imperialism

the Russians suppressed the Hungarian revolt and invaded

Czechoslovakia; and in

the name of anticommunism the Americans carpet‑bombed Hanoi. These are

generally known international issues. But if we look into our own

immediate

political and social surroundings, we are bound to trace back to the

ideal/hypocritical loop, to different degrees at different levels,

whatever

turgescence in the institutions and redundance in the authorities we

may find.

It is, indeed, by confounding ideals with hypocrisy that "the people"

claim citizenship in a democracy without participating in its political

process. And when they do participate, rationalizing their private

interests

into public good, they let interest groups manipulate and control the

political

process and institutions, helping politicians and bureaucrats create

their own

ideal/hypocritical loop.

The "ideal" solution,

keeping in mind all the

socio‑political complexities covered, is political

consciousness and participation on the part of every member

of the society beyond private interests. But that is an ideal which

can be

strived for only if we look closer into ourselves and observe how

often, when

our interests are not at stake, we float on the clouds of idealism, and

how,

when it comes to our precious selves, we descend into the thick of

hypocrisy.

We are the stuff of which politics is made: to understand politics, we

must

first know men, and that is ourselves. Knowledge of the problem is part

of the

solution.