Chapter

11

Political

Culture

The

strongest is never strong enough

to be

always the master, unless

he

transforms strength into right.

Jean-Jacques

Rousseau

The crucial fact of

man's

capacity to exploit human and natural energy led us to inquire about

the

socio-political nature of energy. Power emerged as the raw material

giving

cultures their impulse and propelling their socio-political flux. The

closing

words of our preceding chapter on power converged toward and

complemented the

concluding notes of Chapter Eight, suggesting that the combinations and

conflicts of power complexes, each with its particular identity,

interests and

rationales, do not necessarily follow any predetermined direction. The

implication is that if there is a sense of organization or course for a

social

flux, it depends on the consciousness of the power complexes involved

and their

tendencies.

You may also recall

that in our

studies of value systems and norms we saw that the heterogeneity of

value

systems within a social context could reduce the efficacy of their

particular

moral norms and lead them, if they were to coexist, to patterns of

ethical

norms, and beyond them to the institution of legal norms backed by

coercive

sanctions. You will notice that this normative evolution also converges

towards

our present discussion of power and the consciousness of power

complexes as a

prerequisite for social organization. For when value systems upholding

particular interests compete and conflict, the power they generate may

be

drained. To avoid that possibility, they have to compromise and

cooperate in

establishing rules, processes and institutions, providing norms of

orderly

conduct and a course of action in their coexistence, interactions and

transactions.

In other words, while

power, if

not properly integrated, can cause social and political disruptions,

when

harnessed it can be the source of social order and organization. The

harnessing

of power provides direction for the sociopolitical flux. But it takes

power to

harness power, giving rise to the question as to which is power--that

which is

harnessed or that which harnesses? Political culture is precisely that

aspect

of a social flux which permits the circumvention of this paradox and,

by

transforming one dimension of power into authority,

makes it possible for powers to cohabit.[1]

Interaction

and Interpenetration of Power complexes

Within the social

flux, the

combination of different dimensions of a culture creates power

complexes with

different emphases and characteristics. For example, such powers as an

industrial corporation, a church, or a military organization may

coexist. The

industrial corporation's basis of power is mainly its possession of

means.

Industry involves an interaction between human endeavor and the natural

environment, i.e., manipulating matter and producing means as one of

the

components of power. The church has spiritual power which it maintains

mainly

by persuasion and influence. The army's power may be broadly identified

as

force and coercive potentials. Such schematizations are obviously

incomplete

and could be misleading, for these power structures, while separately

identifiable, fade and shade into each other and into many others. Both

the

church and the army run on the means that, in the form of wealth and

production,

the industrial corporation provides. The church and the corporation

employ

disciplinary and organizational methods similar to those of the army,

and they

also depend on the latter for their security, while the army and the

corporation depend on the faith inculcated by the church for their

cohesion and

moral and ethical standards.

Besides these

interdependencies

and interpenetrations, the powers in our example compete or cooperate

in

overlapping spheres. The farmer, a supplier to all three, is a

potential client

or worker for the industrial corporation, a believer for the church, a

recruit

for the army. If he fell overwhelmingly or exclusively within one

sphere, he

would, to that extent, become a potential instrument for that power.

For

example, the individual who becomes a devout and fanatic believer in a

religion

or an ideology, although he may still provide labor for industry or

serve in an

army, is a more potent instrument in the hands of his church or

ideological

organization which can dictate his behavior in the industry or the

army. A man

who allies his interests primarily with his corporation may overlook

the

religious precepts he is supposed to uphold, or may use the army to

advance his

corporation. And a soldier properly disciplined by the army may take

over or

wreck both the church and industry to win a battle.

The above instances

suggest

that, as power complexes which interdepend and interpenetrate also

clash and

compete, there must be some understanding, laws, patterns of

relationship and norms

of conduct to which they could subscribe for more or less orderly

interactions.

Such understandings will not come about until the contesting powers

become

conscious of not only their own power but also that of their contenders

and its

nature. That is, they must first realize that they cannot overrun the

adversaries or that if they did, their natures would be so incompatible

that

the chunk they had swallowed would be indigestible, might obstruct

their own

system and cause their demise. Or they may see that the existence of

other

power complexes distinct from theirs can complement and balance to

their

advantage.

In a way, politics is

the

reality of this interplay of powers and eloquently portrays the not

always

systematic, not always organic, not always spiritual, and not always

historically determined nature of the adjustments and maladjustments of

power

complexes; for, in their relativity and subjectivity, poker complexes

would not

continue with any identifiable autonomy in the human sense if, once and

for

all, they could systematically and rationally fit and be fitted

together,

making them part of a whole, functioning according to instinctive

reflexes or

mechanical laws. The move toward balance and equilibrium by contending

powers

is not always an end in itself but a subjective and reluctant

compromise.

I.

Conversion of Power into Authority

We can trace to the

earliest

known social context the dynamics and fermentations which, in the

course of

power interactions and interpenetrations, have resulted in the

understandings,

norms of conduct and structures identified as authority. We are using

the term

"authority" broadly at this stage to mean the recognition by the

parties involved of the validity of certain norms and their binding

effects on

their mutual relations. The earliest human associations had rules of

conduct

which evolved not only from the basic human similitude attraction and

gregariousness, but also from their accompanying inhibitions, fears and

expectations. "If I do it to him he will do it to me" or "if I

do it today he may do it tomorrow": such conclusions drawn from

accumulated observations and experiences can lead to mutually

understood

standards of conduct, from moral and ethical norms to legal norms. But,

as we

have seen, the antagonists may also be inclined to do what they can

today

before their antagonists do it tomorrow. Thus, there will soon arise a

need to

define what is supposed to be the standard of action among the power

complexes

involved.

Where powers have

autonomous

spheres with comparatively little overlapping and interpenetration and

little

inclination to bind and commit their destinies to each other, the

arrangements

may remain simply as mutual guarantees, depending on the precarious

balance of

power, as has often been the case with international relations among

sovereign

states. When the powers involved have fluid, interpenetrating spheres

and

interwoven, interdependent activities--and this includes almost all

social

relations, from interpersonal and intergroup to some international

relations

(those between closely related sovereign states, such as the European

Common

Market)--the arrangements include not only norms of conduct but also

responsible bodies--persons and institutions--vested with the authority

to

enforce orderly interaction. There will thus evolve, superimposed

(figuratively

speaking), a power capping the interacting powers, recognized by them

as having

the prerogative to arbitrate, moderate, administer or supervise

(depending on

the nature of their relations) their intercourse.[2]

It is, of course,

likely that

the ensuing arrangements will be concomitant with the power magnitude

of the

different complexes involved, reflecting a hierarchy.[3] So, while establishing standards of

recognition for the respective spheres and competences, the

authoritative

arrangements will also tend to regulate and limit power fluctuations,

at least

in the areas where the powers overlap. This implies that the

established

authority tends to perpetuate the prevailing order of magnitude of the

powers

involved--a fact which in itself, depending on how flexible or rigid

the

arrangements are, can inhibit certain powers. It can also cause

friction among

the powers if provisions for adjustments commensurate with their future

dynamics and expansion are not incorporated into the arrangements.

Thus, with

some lag-because the established order may continue beyond the point of

change

in the magnitude of the powers--some of the powers may challenge the

established authority. If the authority is maintained only by the

mutual

agreement of balancing powers, once some of those powers have ceased to

recognize that authority, it will need to be readapted to the new

balance. It

will, most probably, be upheld by the powers with vested interests in

it, and

if they are strong enough to make it prevail over the challengers, or

if the

authority itself has means of imposing itself (which amounts to the

same

thing), it will prevail. But that authority would be on the verge of

turning

into power.

Herein lies the

distinction

between power and authority, hinging on the degree to which a hierarchy

of

rights, competences, obligations and obediences is imposed by imminent

and

constant external pressure (power), or is recognized, adhered to and

internalized as a matter of course (authority) by the components of the

hierarchy. In the extreme authority is a power that is not challenged

and does

not need to use coercion. Its subjects follow its directions because

what it

directs is right--not only in the legal sense of "a right," but also

in the valuational sense. The doctor who tells you to take two aspirins

to cure

your headache is an authority on the subject and is "right" because

you believe that if you follow his instructions, your headache will be

cured.

But even at this stage

the

doctor's authority is not without power. His authority is based on the

reputation that a physician knows about matters of health. You remember

that,

as we noted in the last chapter, reputation is a source of power. In a

way,

however, the society has bestowed this authority upon the doctor,

either by

permitting him and giving him grounds to build his reputation, and/or

by

creating institutions and procedures by virtue of which he gets his

diploma to

practice medicine--his "right" in the legal sense. This is probably

the nearest we can get to an authority with camouflaged power and an

absence

of pressures and coercive measures. Your acceptance of the doctor's

prescription is, of course, evidence of your conditioning toward his

authority.

You have come to recognize the value of experience and knowledge and,

on the

basis of that recognition, consider the doctor competent.

This essentially has

been the

premise for the recognition of the primus

inter pares (the first among equals) ever since the primeval stages

of

social organization. When the Eskimo tribe assigns the leadership of a

hunting

expedition to the hunter who, according to tribal standards, is most

qualified,

it recognizes him as an authority. His authority, however, is due not

simply to

the fact that he is the best hunter, but that the tribe has assigned

him the leadership. Authority has an attributive character.

In other words, it has one dimension over power. The patient follows

the

doctor's prescription not in a simple, bilateral channel, but within a

triangular pattern of which one side is the patient, the second the

doctor, and

the third the social context which has made medical advice desirable

for the

patient and has recognized the doctor as the holder of medical

knowledge.

We call this third

dimension

the legitimization of power into

authority. If the leader of the hunting expedition is not appointed by

the

tribe but imposes his leadership by force and others follow him for

fear of

reprisals, he is exerting power, not exercising authority. As the third

dimension, legitimization is the element that stabilizes the

power/authority

configuration, giving it a social rationale in the minds of its

subjects, and

thus, with their acquiescence and support, making it more resistant to

internal

or external threats. The third dimension legitimizing authority does

not need

to come from an outside source (although, as we shall see later, that

is

convenient) such as the tribe, but can be generated by the two

dimensions (the

domineering and the dominated) within the power complex. The hunting

expedition

can itself elect a leader whose commands the members of the group

follow not

because they are coerced but because they accept the instituted

authority. Even

those who may not otherwise accept the command of the leader will now

abide by

it, despite their own inclinations, because the group recognizes

leadership. Of

course, the group may also choose the leader because he threatens

usurpation if

he is not elected. By electing him, the group may thus connive to

condition the

powerful and inhibit his arbitrary exercise of power, setting, at the

same

time, a precedent for certain behavior.

Essentially, we are

presented

with an authority/power spectrum where at one end the process of

legitimization

greatly subdues the power characteristics of the authority, as in the

case of

the doctor's authority, while at the other extreme legitimization

barely

disguises power as authority. Within that spectrum, legitimization is

the feat

by which different political cultures transform the power fibers of the

social

flux into authority. And it is indeed a feat: Consider for a moment

that man

has a domination drive, but also the social drives for order and

justice. These

latter are sought by men and by power complexes--men in the social

context--to

secure a reasonable degree of predictability for their freedom of

action and

attainment of their goals. To bring about order and justice, there must

be

norms: moral, ethical and legal (laws, in the general sense). To have

laws we

need authority. But to have authority, we need to legitimize

power--through

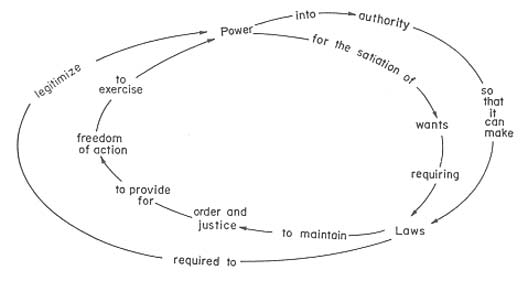

laws! (See Fig. 11-01.)

Fig.

11-01

To comprehend the tour de force of legitimization of power

into authority and its variations within different social contexts, we

need to

look again at some of the social phenomena examined. First, we have to

recognize that the basic ingredients remain power and the general

tendency of

power complexes, in their coexistence and interaction, toward some

arrangements

for order. Of course, in particular circumstances during the passage

from one

order to another, certain power complexes may instead seek chaos and

confusion.

We then have to look for the concoctions of powers bringing about the

third

dimension of the triangle that converts power into authority. This may

take

place either through a separate power acting as the third side of the

triangle,

such as the church legitimizing a ruler's power, or by the development

within

a power complex of a third dimension of recognition and acceptance

between the

submitting and dominating hierarchies. A constitution exemplifies the

latter

case.

Some power complexes,

because

of the composition of their sources, are more apt to act as

legitimizing agents

than others. The church, for instance, with its emphasis on belief, can

more

efficiently inculcate its followers to consider a secular power

legitimate,

than a military power controlling a population can impose the authority

of a

given belief--although the possibility of the latter case should not

be

excluded. It is simply a question of degrees. The early Mohammedan

armies did

convert the conquered people by the force of arms and heavy taxation of

the

unbelievers; and although the early non-Arab Moslems probably adhered

to that

religion for financial convenience and fear for their lives, eventually

the

continuation of Arab domination perpetuated the Islamic faith in many

of the

conquered lands and established it as an authority.

In general terms, the

sources

of power that are efficacious and instrumental in legitimization are

those that

find their way to the "inside" of man: his brain, his heart, his

glands and his stomach. It is difficult to identify the specific

appeals to

each particular sector. That is why in Chapter Three we elaborated our

affectional/functional spectrum. When within a power complex the

domineering

hierarchy appeals to the individual's feelings (his heart, in the

popular

sense), these feelings arouse him (by glandular secretions?) through

evocation

of certain established internal patterns (in his brain)--patterns which

may not

be rational--remember our discussion of values and symbolic systems. A

rationale--an appeal to man's rationality (his brain)--supporting the

prevailing order should also have a functional base such as the

satisfaction of

material needs (keeping his stomach full) and some comforts (glandular,

either.

in the positive sense of feeling pleasure or the negative sense of

fearing and

avoiding pain).

Thus, the range of

appeals to

man's "inside" has a gradation from "deep inside" to

"nearly outside"; from the man who believes--or is made to

believe--by persuasion and inculcation, or rationally accepts and

participates

in a social order, to the man who goes along because he is materially

rewarded

to do so or fears the consequences of noncompliance. At the extreme

"outside," the domineering factor in a power complex imposes itself

by sheer force, means and position, and in so far as it does not

penetrate, it

is constantly resisted without even developing a continuous and

predictable

fear pattern within those it dominates. The dominated may sometimes

fear a

clash with its superior but may not internalize it as a pattern of

behavior

towards that power. The Yugoslav partisan in World War II did not

accept the

authority of the German occupation and challenged its power. The German

occupation forces had not managed to appeal to any sector of the

partisan's

"inside."

We may, in summary,

retain

three main interrelated dimensions in the conversion of power into

authority;

namely, 1) the relative non-coerced

recognition factor; 2) the "third" attributive dimension in the

triangle of legitimization, either

provided by a separate power or developed within the power complex

between the

domineering and dominated factors; and 3) the complementary condition

for the

above two of some penetration of the

authoritative pattern either through affectional and belief

dispositions or

functional rationales. Considering the legitimization process in the

light of

penetration and noncoerced recognition we may envision two broad--and

obviously

interpenetrating--patterns for the conversion of power into authority,

which we

shall identify as consecration and constitutionalization.[4]

Consecration

Consecration is the

more

nonrational, valuational and affectional pattern. Within it are two

further

interacting dimensions we may identify as the spiritual

and the traditional.

The spiritual has been the most recurrent and most persistent of the

legitimizing factors of authority. In the words of Machiavelli:

In

truth, there never was any remarkable lawgiver amongst any people who

did not

resort to divine authority, as otherwise his laws would not have been

accepted

by the people; for there are many good laws, the importance of which is

known

to the sagacious lawgiver, but the reasons for which are not

sufficiently

evident to enable him to persuade others to submit to them; and

therefore do

wise men, for the purpose of removing this difficulty, resort to divine

authority.[5]

Hobbes put it this way:

And

therefore the first Founders, and Legislators of Common-wealths amongst

the

Gentiles, whose ends were only to keep the people in obedience, and

peace, have

in all places taken care; First, to imprint in their minds a beliefe,

that

those precepts which they gave concerning Religion, might not be

thought to

proceed from their own device, but from the dictates of some God, or

other

Spirit; or else that they themselves were of a higher nature than mere

mortalls

that their Lawes might the more easily be received: So Numa

Pompilius pretended to receive the

Ceremonies he instituted amongst the Romans, from the Nymph Egeria: and

the

first King and founder of the Kingdome of Peru, pretended himselfe and

his wife

to be the children of the Sunne: and Mahomet, to set

up his new Religion, pretended to have conferences with the

Holy Ghost, in forme of a Dove. Secondly, they have had a care, to make

it

believed, that the same things were displeasing to the Gods, which were

forbidden by the Lawes. Thirdly, to prescribe Ceremonies,

Supplications,

Sacrifices, and Festivalls, by which

This power of the

holders of

faith to consecrate authority becomes more evident when we realize that

the

pivotal premise for legitimizing power into authority is valuational.

Power

remains "power" as long as its doings are identified as

selfinterest-oriented.

Recognition of power by holders of faith sublimates it into authority. An authority is

presumed not to

act only for its own good but for the good of those it is ordering and

administering.

The belief system, of course, as long as it exists, is the supreme

consecration. Authority is so much the more authority when the good it

administers is ordained by a supreme author whose dictates are the

standard for

both the ruler and the ruled. However, the good of the ruler and that

of the

ruled may have been standardized differently, sometimes drastically so,

so that

according to the supreme author the ruler gets nearly everything, while

the

ruled barely subsist.

From the mana

of the chief in the primeval society to "so help me

God" in the presidential pledge of the United States, authority is

accompanied by the consecration of the supernatural. The call of the U.

S.

President for help is, of course, a much attenuated case of

consecration and,

as we shall see later, can better be identified as

constitutionalization.[7] But the belief institution is a potent and

efficacious value-forming agency, and secular social and political

powers seek

its support and collusion. As of the fourth millenium B. C., the

pharaohs of

Egypt were identified as the living reincarnations of the gods. In

Sumer the

gods ruled through their representations on earth by the corporation of

priests

and the secular rulers. We said that the third side of the triangle of

legitimization

could be contained in the nature of the relationship between the

dominating and

dominated, and a good instance of this occurs when the spiritual power

is also

vested with the secular authority in the theocratic sense, as was the

case in

Sumer, in Tibet until recently, and still is in the Vatican State.

These are

clear examples of theocracy or rule by god, with his spiritual servants

fulfilling the secular duties on his behalf.

Studying the

pre-Columbian

cultures of the Andes and Mexico, Julian Steward speculated that

...the

increasing population and the growing need for political integration

very

probably would have created small states in each area, and these states

would

almost certainly have been strongly theocratic, because the

supernatural aspects

of farming -- for example, fertility concepts, the need to reckon

seasons and to

forecast the rise and fall of rivers, and the like -- would have placed

power in

the hands of religious leaders.[8]

By empirical

standards,

Steward's statement may sound too deterministic. Not every reliance of

authority on spiritual and supernatural premises turns into theocracy.

The

early political structures of Egypt and China, which developed under

similar

conditions, were not strictly theocratic, although they were strongly

dependent

on the supernatural for the legitimization of their authority.

In legitimizing power

into

authority, consecration may also draw on tradition. What qualifies the

spiritual and the traditional as consecrating factors is their

affectional,

nonrational dimension. This common characteristic may sometimes make

the

identification of one or the other source of consecration difficult,

because

they intermingle. In China and Japan we find cases where the

legitimizing

dimension for converting power into authority was developed within the

traditional rather than the spiritual context. Although not strictly

theocratic, this development was based on the concept of the unity of

religion

and the state. The earliest native Japanese chronicles, Records

of Ancient Matters (Kojiki) and Chronicles of Japan

(Nihongi), written in 712 and 720 A. D.

respectively, were apparently compiled with a view to substantiating

the

political claims of the Japanese ruling dynasty, formulating the

history of

Japan along the Chinese traditional patterns. As Tsunoda, de Bary and

Keene put

it:

As for

the assumption of absolute powers, which made the Japanese king a

divine

emperor (Tenno), it plainly derives from the already fully developed

autocracy

of China, justified by the Mandate of Heaven. The successive steps

taken toward

the establishment of a strong central government reflect Japanese

adherence to

the Chinese concept of the sovereign as the possessor of the Mandate of

Heaven.

Prince Sholoku's Constitution, the Taika Reforms, the adoption of

Chinese legal

and bureaucratic institutions, were all intended to strengthen the

claims of

the emperor to being a true Son of Heaven, a polar star about whom the

Lesser

celestial Luminaries turned.[9]

Traditional

consecration

implies continuity, an element used to justify hereditary monarchies.

Traditional continuity, however, is more than a hereditary claim to

authority.

It may englobe monarchy but supersede heredity. When in 1924 the

Persian Prime

Minister, Reza Khan, tried to establish a republic to overthrow the

reigning

dynasty, his attempt was frustrated by strong religious and traditional

opposition.[10] Yet a year later he ousted that dynasty and

was enthroned as Reza Shah, beginning the Pahlevi dynasty. In 1971 his

son,

Mohammed Reza Shah, celebrated the 2,500th anniversary of monarchy in

Iran

(despite the numerous vicissitudes of different dynasties of domestic

and

foreign origins since the monarchy was formed in that country), to

emphasize

the traditional continuity of rule in Iran.

Although they

intermingle, the

distinction between the spiritual and traditional aspects of

consecration are

helpful for analyzing the evolutions of certain political cultures,

notably

those where a power tries to maintain itself without a traditional

foothold. It

is not possible to become part of a tradition without the temporal

dimension

but the recognition of the spiritual dimensions of a traditional

culture can

provide a back door for legitimizing a power into authority over an

alien

culture. Cyrus, the Persian Emperor, in his charter of 539 B. C., paid

tribute

to the Babylonian god Marduk, which was his way of claiming succession

from the

Babylonian kings.

Inversely, where no

well-established spiritual doctrine upholds a ruler's authority and

provides

predictable patterns of behavior for the subjects, the secular powers

may seek

to have one developed. In 990, Vladimir, King of the Russians,

converted his

people en masse to Christianity.

Legend says Vladimir reviewed several religions and finally chose the

Greek

Orthodox. He discarded Judaism and Islam because they prohibited eating

pork

and drinking wine--conditions difficult to fulfill in Russia. He chose

Greek

Orthodoxy so the Russian church would fall under the canonical

authority of the

Patriarch of Constantinople rather than the Church of Rome, which he

considered

too strong and too meddlesome in the political affairs of secular

powers.

This last point leads

us to the

underlying political complexities of consecration by a separate power

in the

legitimization of authority. Although Vladimir would probably have

opted for

the Greek church anyway because Russians had a closer knowledge of it,

his

alleged political considerations reveal the rivalry between the

spiritual and

temporal powers. The pages of history are full of church and state

conflicts,

competitions, combinations and cooperations. The high priests of Amon

finally

sat on the throne of Egypt (1090-945 B. C.), while the Libyan princes

became

the high priests of Amon (ca. 850 B. C.). Speaking of the Brahmins of

India,

Thapar says:

The

priests were not slow to realize the significance of-the supreme

authority

which could be invested in the highest caste: They not only managed to

usurp

position by claiming that they alone could bestow divinity on the king,

but

they also gave religious sanctions to caste divisions.[11]

Where the spiritual

and

traditional dimensions of the society develop patterns independent of

each

other, the triangularity of consecration becomes more apparent, and the

combination of the three components of the power/ authority complex,

i.e., the

domineering and dominated dimensions of power and the legitimizing

factor, can

give rise to different political cultures. It is understandable that

the power

serving as the legitimizing dimension can itself develop claims to

authority,

which raises the possibility of rivalries and the tendency of the

powers to

seek legitimizing processes not dependent on other powers which can

unduly

hamper them. The partnership of church and state in Western Europe is

not only

a plastic illustration of the spiritual and traditional dimensions of

consecration, and the struggles of church and state for supremacy, but

its

historical evolution leads us to the other aspect of legitimization of

power

into authority, namely, constitutionalization. The history of Europe,

from the

decline of the Roman Empire to the emergence of the Holy Roman Empire,

was a

tapestry woven with threads of two traditions--the Roman and the

Germanic--and

one belief, Christianity. In that canvas the spiritual served as a

carrier

between the two traditions; and the three in their conflicts,

compromises and

accommodations shaped Western culture. We can trace most of our modern

laws,

customs, institutions and ideologies to that tapestry. Let us, then,

make an

incursion into that history and the political thoughts and realities it

begot.

*

* *

In 312, in a Roman

Empire that

had persecuted Christians for centuries and had nearly developed a

belief that

its emperors were gods, one of those emperors became a Christian.

Constantine

was converted, it is said, after having a vision of the cross before a

battle.

The fact that ever greater numbers of the Roman population were

embracing

Christianity, and that claiming the same faith as his subjects was good

statesmanship, may not have been totally outside Constantine's vision.

In the

manner of earlier Roman emperors asserting themselves as the embodiment

of the

cults of their times, he claimed to oversee the affairs of the church.

In 325,

he summoned and presided over the first ecumenical council. But the

early

Christian beliefs and the imperial traditions did not marry easily. In

380;

Emperor Theodosius prohibited all public religious professions except

Christianity, but later he was excommunicated until he repented for

having

ordered the massacre of some 7,000 citizens of Thessalonica in reprisal

for a

riot. He did repent, but the question as to whether the emperor was in

the

church of Christ and therefore subject to it or was instead above it

remained unsettled.

In his City

of God (413-427) St. Augustine propounded the theory of

spiritual and temporal dualism. The spiritual world was represented by

the

heavenly city, the Christian church, which was concerned with the

salvation of

man's soul. The earthly city, represented by Rome, was the frame of

man's

mortal life. In his earthly city man, driven by passion, egoism and

self-love,

had to submit to law and government to maintain peace:

The

earthly city, which does not live by faith, seeks an earthly peace, and

the

end it proposes, in the well-ordered concord of civic obedience and

rule, is

the combination of men's wills to attain the things which are helpful

to this

life. The heavenly city, or rather the part of it which sojourns on

earth and

lives by faith, makes use of this peace only because it must, until

this mortal

condition which necessitates it shall pass away.[12]

When, in 476 at

Ravenna,

Odoacer of the Germanic Herul tribes deposed Romulus Augustulus

(traditionally

the last of the Western Roman Emperors), he asked Emperor Zeno of the

Eastern

Roman Empire for the title of patrician. He sought a traditional rather

than a

spiritual consecration. The role of the church as a sovereign

legitimizing body

was still debatable. Zeno's claim in his Henoticon

(482 A. D.) that the emperor (of the Eastern Roman Empire) had the

right to

define theological doctrine prompted Pope Gelasius to proclaim his

independence

from the secular power and to assert that "two swords" rule the

Christian world, the sacerdotium and

the imperium. "Christian

emperors need bishops for the sake of eternal life, and bishops make

use of

imperial regulations to order the course of temporal affairs."[13]

In the centuries that

followed,

as the Western Roman Empire petered out, with disruptive barbarian

invasions

and settlements in Italy (passing some Christian bishoprics into

barbarian

territory) the Church of Rome with its bishop-the Pope--became more

involved in

secular affairs. By the sixth century, Gregory the Great (Pope,

590-604) assumed

the role of emperor in the West, took care of the civil works, received

pay

from Constantinople for the army, appointed governors and directed

generals.

His missionary campaigns to convert the German people started the turn

from the

Greco-Roman tradition to the medieval Romano-German combination. Yet,

although

the Byzantine Emperor in Constantinople had little effective power

on-the

Italian peninsula, his authority lingered as the continuation of the

traditional Roman Empire of which the church was considered a part.

In the eighth century

when

Pepin, the Carolingian, wanted to usurp the declining Frankish kingdom

of the

Merovingians, he faced a problem of legitimacy which was partly

related to

this traditional structure of the Roman Empire. The founder of the

dynasty he

wanted to overthrow, Clovis (481-511), had received his title as

patrician from

the Roman Emperor. The legitimists considered Pepin a usurper when, on

the

advice of Pope Stephen II, and drawing on Frankish (German) tradition,

he

presented himself at the traditional electoral rites of the Franks and

was

proclaimed King in 752. The Pope, needing an ally to free himself from

the

authority of the Eastern Roman Empire and to cope with the threatening

expansion of the Lombards in Italy, anointed Pepin Christian King of

the Franks

and Roman Patrician. (a title which could be legally bestowed only by

the

Emperor in Constantinople). By doing so, the Pope solidified his

position as

the temporal heir to the Roman Empire in Italy, thus claiming both

spiritual

and traditional prerogatives to legitimize Pepin's secular authority.

But in that alliance

the

traditional pattern of the old Germanic tribes was present. Its

combination,

cooperation and competition with the papal authority in Rome eventually

developed

a new political pattern in Europe.

Pepin's son

Charlemagne further

expanded the Frankish kingdom. In 795, the newly elected Pope Leo III

sent

Charlemagne the notification of his election with the key to St.

Peter's and

the banner of Rome. The notification, previously addressed only to the

Byzantine emperors, assimilated Charlemagne to them, while the

accompanying

banner implied his recognition as a commander of the church and supreme

judge

of Rome. In 800, Charlemagne presided over a solemn tribunal in Rome to

have

Pope Leo III cleared of charges of perjury and adultery. At the

Christmas

prayers that year, Leo placed a crown on Charlemagne's head and

proclaimed him

Emperor. By so doing, Leo was providing Rome with a new authority and

himself

with a new source of support, reviving the Western Roman Empire with

its dual

temporal and spiritual authorities--except that the traditional

background of

its temporal power shifted from Greco-Roman to Germanic.

While Charlemagne's

conquests

brought new flocks under the Pope's spiritual authority, he was also

making it

clear that the Pope was a vicar in his kingdom who was to "pray to God

for

the benediction of the Christian people," while the prince was "to

govern the church of God and defend it from the wicked." He chose his

title: "Charles, serenisime August, crowned by God, great and pacific

emperor governing the Roman Empire, by God's misericord King of the

Franks and

the Lombards." Notice "crowned by God," suggesting that the Pope

who crowned him was only an accessory of divine providence. Therein lay

the

ingredients which provided a basis for the concept that the temporal

ruler was

god's vice-regent by divine providence and, later, by divine right of

kings. In

the following centuries many popes claimed supremacy because of their

spiritual position and many kings denied it because of their secular

authority,

whose actuality was proof that divine providence rather than papal act

was

their essential legitimizing source. Thus, both the temporal and

spiritual powers

invoked divine consecration of their political authority to rule. The

conflict

had, of course, concrete political and economic aims such as the choice

of

bishops and their prerogatives, the ecclesiastical land holdings which

increased through donations to the church and their taxation by the

king of the

land. But the challenge between church and state was often fought on

legal and

philosophical grounds.

By the thirteenth

century, the

legitimacy of the secular power on the basis of the divine right of

kings began

to have strong supporters. Dante (12651321), in his De

Monarchia, concluded that "the authority of temporal

monarchy descends, without mediation, from the fountain of universal

authority."[14] In other words, it comes directly from

"divine providence," without need of the church's intermission. John

of Paris used Aristotelian logic to show that the King of France is not

bound

by the Pope or the Emperor for his action on behalf of his kingdom.

The heated debate over

the

legitimacy of the spiritual and secular powers continued through the

Renaissance and the Reformation, partly as cause and partly as

consequence of

those historical phenomena. As the disastrous religious conflicts

dragged on

and the powers of the Pope and the Emperor as the dual authorities of

the

faltering Holy Roman Empire lost effectiveness in maintaining peace and

order,

the divine right of kings received new impetus as the legitimizing

source of

monarchical power in the emerging political entities. The results were

new

clashes and conflicts, but also new power complexes and combinations

culminating in the concept of sovereignty, to which we shall turn

later. As for

the protagonists of the divine right of kings, let us quote James I's

speech of

1609:

Kings

are justly called Gods, for that they exercise a manner or resemblance

of

divine power upon earth: ...they have power of raising, and casting

down: of

life, and of death: Judges over all their subjects, and in all causes,

and yet

accountable to none but God only ....And to the King is due both the

affection

of the soul, and the service of the body of his subjects.

The third legitimizing

dimension of royal authority thus did not require consecration by the

church

but emanated directly from the abstract divine power. The categoric

tone of

James' statement, however, implied that his divine right was being

contested.

The contestant was the Parliament which will be a central figure in our

coming

study of constitutionalization.

In the last analysis,

consecration stems from the ever-present affectional, nonrational and

valuational dimensions of man which prime his recognition and

acceptance of

many aspects of political institutions, behavior and processes. The

present

Shah of Iran has, on many occasions, asserted having supernatural

protection,[15]

which can be understood only in the light of the political culture of

that

country. At the turn of the century McKinley invoked the power of

prayer and

God's guidance in his decision to keep the Philippines under American

rule, and

in the heated debates on the impeachment of Richard Nixon a number of

Americans

(not a majority, according to the polls, but still some) were indignant

at the

thought of disrespect for the awesome office of the presidency which

had God's

protection. Because of its affectional and valuational potentials,

consecration

remains a potential legitimizing process. Our examination of the

evolution from

consecration to constitutionalization in the context of Western

political

culture should not lead to the conclusion that one inevitably follows

the

other. Indeed, if we look further into European history we find that a

reverse

process did take place in antiquity where the early Roman Republic

eventually

turned into an empire (with hereditary and adoptive processes of

legitimization).

Some of this also took place among the German people whose earlier

elective

monarchies became more hereditary during the middle ages. To continue

our

present inquiry, we should above all keep in mind the traditional

aspects,

which are pervasive social phenomena and in fact constitute a common

ground for

consecration and constitutionalization.

Constitutionalization

Our discussion has

implied that

consecration was by and large the way of the past in Western culture,

with only

a few remnants traceable in modern times. We may also have suggested

that

constitutionalization is the modern way of legitimizing power into

authority.

While it is relatively easy (by following the development of

rationalism and

individualism, of communications and education) to demonstrate the

advent of

constitutionalization as the legitimizing process in modern Europe, we

may

distort the picture if we do not scrutinize its origins and traces

within the

European historical evolution we have used to illustrate the conversion

of

power into authority.

Constitutionalization, as we

have implied, is the process by which legitimization of power into

authority

develops mainly within and among the components of a power complex,

with little

or no intervention by or resort to an outside factor--in particular the

supernatural. Constitutionalization legitimizes authority with the

direct or

indirect participation of those who will submit and will possibly be

represented. This does not imply, however, that legitimization takes

place

uniformly between the authority and all those subject to it, nor that

it takes

place on a purely functional and systematic contractual basis. The

Magna Carta

(1215), often mentioned as the first document of modern democracy, was

neither

a proviso for popular participation in government nor a contract

between two

parties setting down brand-new functional and systematic rules of

conduct. It

was an understanding between King John and the feudal lords (the

weightier part

of those submitting to the king's authority) to set down their

understanding of

traditional patterns which had evolved within the kingdom. It reflected

the

barons' consciousness of their power and their claim to a share in the

king's

authority. More concretely, King John's loss of his vassals in France

north of the

Loire to Philip in 1204 reduced his support outside England, increasing

the

power of the English barons in the kingdom. Simultaneously, the

increase in the

king's demands on the barons to carry on his campaigns on the continent

caused

conflict, notably over "scutage" (taxes paid by the barons to the

king), the recruitment of soldiers, and for the king's adventures on

the

continent. These factors put the barons in a bargaining position for

more say

in the affairs of the kingdom. The functional, systematic and

contractual

dimensions were framed in the context of the cultural dynamics and

fermentations which were traditional.

You may notice that

our

discussion, while emphasizing the traditional aspect of

constitutionalization,

adds two further patterns -- the contractual

and the representational. By

"contractual" we do not necessarily mean an incipient social contract

in the Lockean sense, but rather the evolution of understanding as to

the

extent and nature of authority between the authority and those who

submit, like

that defined in the Magna Carta. The distinction between the

contractual and

representational implies that by participating in

constitutionalization, those

who submit will not necessarily participate in exercising the authority

nor be

represented within it.

Looking again at our

European

model, we find that when the Carolingian Empire began, some of the

Germans had

already mingled their culture with that of the Romans. But that had

happened

mostly in the areas of overlapping populations such as northern Italy

and parts

of the Frankish kingdom. Otherwise, the German traditions had remained

mainly

tribal and customary. Tribal patterns varied among different German

peoples,

but in legitimizing power into authority they generally combined

supernatural, territorial,

hereditary and electoral dimensions. This last implies a

constitutionalizing

factor. The earliest known forms of government of the German people

were tribal

democracies under kings or grafs elected by tribal assemblies. There

were no

restrictions on the choice of grafs, while the kings had to be elected

from the

royal houses which had some supernatural consecration of their ancestry

and

hereditary rights. That was another reason why, as we noticed earlier,

Pepin,

though elected by the magnates, was still considered a usurper, because

he did

not descend from a traditional kingly house.

In their moves and

expansions

in Europe, the German tribes developed systems of authority containing

the

germs of the medieval and feudal system of Europe. The tribe, in

settling a

territory, whether to cultivate it or to rule it, made interpersonal

arrangements between those who took charge of the land and the

authoritative

tribal chief, whom they would provide with men and supplies for further

expansion and defense. Thus, the authority structure, while having

traditional--and sometimes supernatural--patterns, also had

contractual,

functional and utilitarian features; i.e., there was a mutual

commitment

understood to be beneficial for both the prince and the person who

received a

fief. Fiefs, while inheritable, were not automatically inherited. When

a vassal

died his fief theoretically reverted to the lord until the heir became

of age

to take an oath of fealty and receive investiture.[16]

These feudal

socio-economic and

military arrangements were made within the customary and traditional

framework

to which the prince himself was a subject. He followed the laws of the

tribe he

ruled, and if he promulgated new laws he first consulted the wise men

of his

kingdom and followed the tribal consensus. These traditional Germanic

patterns

and common law practices evolved with the structurally more developed

Roman

civil law and within the realities of the conversion of the Germans to

Christianity. Yet as late as 864, the edictum

pistense maintained the basic Germanic premise of popular consensus

for the

law: "Quoniam lex consensu populi et

constitutione regis fit," i.e., that law is made of popular consent

and the constitution of the kingdom.

The Germanic monarchy,

particularly after the foundation of the Holy Roman Empire by Frederick

I in

the twelfth century, tended more and more towards aristocratic and

hereditary

arrangements. The electoral pattern of authority evolved, and as the

tribal

entities submerged into bigger political structures, the original

election by

tribal chieftains passed on to tenants-in-chief, then to a group of

them

designated as electors with the provision that their decision be

ratified by

the others. Finally the electors' choice became conclusive. The Golden

Bull of

1356 (which remained in force until 1806) transformed the empire into

an

aristocratic federation and provided for an electoral body (patently

aristocratic) to constitutionalize the emperor's authority over the

German

people according to hereditary traditions.

The ideas of

representation

that developed in the late middle ages and challenged the authorities

of both

popes and monarchs reflected not only the ancient Greco-Roman

democratic and

republican practices but also the old Germanic tribal traditions and

constitutionalization processes. Marsiglio of Padua (1280-1343), while

using

Aristotelian logic and Roman antecedents within the Christian context,

also

based himself on traditional patterns when he advocated that "the

authority to make or institute laws belongs only to the corporation of

citizens, or to its more weighty part," and advocated a representative

legislature to be "the primary cause which effects, institutes and

determines the other offices or parts of the state" while "the

secondary and, as it were, instrumental or executive cause is the

ruler,

through the authority conferred upon him by the legislator and in

accordance

with the form which it has established for him."[17]

The

constitutionalization of

authority developed differently in different countries of Europe,

sometimes in

combination with the consecrated authority of the monarch, other times

in

head-on clashes with it. As we pointed out, the Magna Carta was not a

charter

for rule by the people, but it was a beginning. By 1265, de Montfort's

Parliament, consisting of two knights from each shire and two burgesses

from

each borough, was the first semblance of a representative body in

England.[18] In France in 1302 Philip IV called an

Estates-General, including the nobility, the clergy and the

representatives of

the towns in their feudal capacity, mainly to endorse his struggle with

the

Pope. These representative assemblies, while containing the germ of the

later

legitimization, did not then have the prerogative to constitutionalize

the ruler's

authority. They were the outcome of the new political circumstances

created by

the conflicts between the Pope and the monarchs and the nascent

nation-states,

and were instruments serving the purposes of royal taxation. While the

French

Estates-General gained little control in the kingdom, serving mainly as

an

intermittent royal instrument, the English Parliament evolved as a

political

power gradually challenging the king's authority. By 1470, Sir John

Fortescue,

comparing England with France in his De

Laudibus Legum Anglie distinguished between the regal right of the

king and

the political rights of the people in England, which was not the case

in France

where only the King ruled, regally. He wrote:

The

kynge of England can not alter nor change the lawes of his royalme at

his

pleasure. For why he governeth his people by power not only royal but

also

politique. If his power over them were royall onely then he myght

change the

Lawes of his royalme, and charge his subjects with tallage, and other

burdens

without their consent ....But from this much differeth the power of a

kynge,

whose government over his people is politique, For he can [not] change

Lawes

without the consent of his subjects.[19]

The religious wars

resulted in

the creation of political entities over which princes claimed exclusive

control, independent of the Pope and the Emperor, but they also

produced

counter-currents against abuses by kings who had sway over subjects of

different faiths.[20] Within both Catholic and Protestant camps

voices advocated resistance against the rulers who were using their

authority

tyrannically. Those who spoke against tyrants were, of course, those

who were

prosecuted for their religious differences with the monarch. Thus, the

writings

of Protestants and Calvinists such as John Knox (The First

Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women,

1557) or George Buchanan (De Jure Regni

apud Scotos, 1579) implicated the Catholic monarchs, while those of

the

Jesuits like Mariana (De Rege et Regis

Institutione, 1599) or Suarez (De legibus, ac Deo

legislatore, 1603) were directed against the Protestant

kings. In their plea or militancy for resistance against the monarch's

authority, however, all had to justify their position by demonstrating

that the

people, or their representatives, were entitled to question the doings

of their

ruler. They were able to do so by showing that, in one way or another,

the

people were the premise whence the king received his authority. The

Huguenot Vindiciae contra tyrannos (1579) maintained

that while "it is God that does appoint kings-the people establish

kings,

put the sceptre in their hands, and with their suffrages, approve the

election." Thus, the idea of a covenant between the people and the

ruler

was developed.

In England the

conflicts

between the Stuart kings and the Parliament, civil wars and the interim

of

Cromwellian commonwealth, all furthered, by the end of the seventeenth

century,

an understanding of monarchy recognizing the king's authority on the

traditional and "contractual" bases of constitutionalization. The

Convention Parliament of 1689 declared: "That king James II, having

endeavored to subvert the constitution

of the kingdom by breaking the original

contract between king and people ...and having withdrawn himself

out of the

kingdom, has abdicated the government, and that the throne is vacant"

(italics mine). The crown was offered to William and Mary with an

accompanying

Declaration of Rights, enumerating the "true, ancient, and indubitable

rights of the people of this realm" which William and Mary accepted to

be

declared King and Queen. That Glorious Revolution moved the

legitimization of

the king's authority from consecration from above (by God) to

constitutionalization from below (by the people of the kingdom--not all

the

people, but the weightier part--the nobles and the gentry).

"The people" thus

emerged as a new pretender claiming to legitimize the authority of the

governments of the new political entities--the nation-states --which

were

reshaping the face of Europe upon the collapse of the Holy Roman

Empire. The

people, however, were as amorphous a source as the divine right. "The

royalist Sir Robert Filmer had great fun demonstrating that the House

of

Commons was elected by less than one-tenth of the people of England."[21] For our present discussion it matters not

whether, then or now, more than ten percent of a population actively

and

effectively participate in the choice of a country's rulers, but how

the

introduction of the people as a participatory factor in legitimization

eventually led to representative forms of government.

While the introduction

of

"the people" has brought us to the core of constitutionalization,

"the people" is a variable which can be viewed and interpreted

differently according to different political cultures and their stages

of

evolution. Using our reference group model discussed in Chapter Eight

as one

possible yardstick to identify "the people," and applying it to one

of the political cultures most closely associated with

constitutionalization,

the United States of America, we find that at its inception "the

people" who could participate in legitimization were restrictively

defined. The electorate was limited on the basis of status (ownership

of

property), age (adulthood), race, sex, and education (ability to pass a

literacy test). Some of these standards prevailed until very recently,

leaving

quite a number of "people" out. An understanding of the nature of

constitutionalization, therefore, requires its dilution into other

legal, economic

and social dimensions of the political culture. This is what we propose

to do

next.

II.

Transitional Period in the West

We will better examine

and

understand the evolution of this period if we remember that the

conversion of

power into authority hinges on law (as illustrated in Fig. 11-1). To

become

authority, power has to be steeped in law. Whoever constitutes the

source of

law can legitimize power into authority and either exercise authority

or

delegate it through legitimization.

Laws:

Natural, Customary, Common and Statutory

The medieval pattern

of

authority, as we have seen, was an intricate complex of

understandings--and

misunderstandings--which held the European societies together under the

supreme

power of God. It was to this nebulous source of authority that rulers

referred

to justify their governments. In other words, their rule and their

laws, in so

far as they contained a change, modification or addition to what was

already

customary or common, were not supposed to be innovations emanating

directly

from the will or whim of the prince, but to be based on laws of the

kingdom of

God which the ruler, ordained by divine providence, could and should

discover

and interpret. This was the natural law which, as St. Thomas put it,

was based

on the understanding "that all the things which the practical reason

naturally apprehends as man's good belong to the precepts of the

natural law

under the form of things to be done or avoided."[22] He implied there were certain laws in nature

corresponding to human nature which man, endowed by reason, could

discover and

apply for the common good. Because this natural law applied to all men,

including those who discovered and interpreted it, the ruler was under

the law,

not above it.

The ruler, as we saw,

was also

expected to respect the customary law of the land. Indeed, the

customary law

and the traditional patterns contained the modalities by which the

ruler was

invested with authority. Further, these patterns and customs provided

the

framework for the administration of justice, which developed into the

common

law.[23]

Thus, authority was

immersed

within the laws it represented. This was the pattern, by and large. It

was not,

of course, exclusive, but subject to human conditions. The ruler, in

his

prerogatives to interpret and discover the natural laws and implement

the

common laws, had an angle of vision conditioned by his particular

interests

and Weltanschauung; and, depending on

circumstances, he enjoyed some leeway for deviation. If the precepts of

religion were strongly upheld by the weightier members of the realm, he

probably had more leeway in secular affairs. For example, while St.

Thomas

condemned unjust human laws that burdened the subjects for the cupidity

or

vainglory of the authority, or those that went beyond the powers

invested in

the authority, or those that were imposed unequally on the community;

and while

he recognized that such laws did not bind in conscience, he qualified

his

argument by adding, "except perhaps in order to avoid scandal or

disturbance,

for which cause a man should even yield in his right, according to Matt. V. 40.41: If a man…take away thy coat,

let go thy cloak also unto him; and whosoever will force thee one mile,

go with

him other two." But he admitted of no leniency for "laws of tyrants

inducing to idolatry, or to anything else contrary to divine law. Laws

of this

kind must in no way be observed, because, as is stated in Acts.

V. 29. we ought to obey God rather than men."[24]

With the Reformation

some

monarchs could claim greater control over the religious affairs in

their land,

and their leeway leaned towards church affairs rather than the common

law of

the land which was, at times, upheld against their arbitrary

encroachments.

.For example, in England in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,

while the

establishment of the Anglican Church was freeing the King from papal

authority,

he was often called to order in respect to the common law. As Sir

Edward Coke

(1552-1634), Attorney General to Elizabeth, later Chief Justice under

James I,

put it, "the common law hath admeasured the King's prerogative."[25]

What was significant

in the

latter evolution was the shift of importance from one source of law,

the

supernatural, to the other, the people. Natural law was made beyond

men, who

were subject to it, and the political authority was to discover,

interpret and

execute it. The common law, on the other hand, evolved from within the

people,

within the traditional texture. Therefore it was supposed to be within

their grasp--not

necessarily their rational but at least their affectional grasp. The

following

dialogue from the trial of William Penn illustrates the point:

PENN: I

affirm I have broken no Law, nor am I guilty of the Indictment, that is

laid to

my charge, and to the end, the Bench, the Jury, and my self, with these

that

hear us, may have a more direct understanding of this procedure, I

desire you

would let me know by what Law it is you prosecute me, and upon what Law

you

ground my indictment.

RECORDER:

Upon the common Law.

PENN:

Where is that common Law?

RECORDER:

You must not think that I am able to run up so many years, and over so

many

adjudged Cases, which we call Common Law to answer your curiosity.

PENN:

This Answer I am sure is very short of my Question, for if it be

Common, it

should not be so hard to produce.[26]

Of course, as long as

law was

customary and traditional, while its fountainhead was the people, they

could

not claim its authorship in any generation or given time. That would

have

allowed them to change the law by simple deliberation. We saw that the

traditional was so qualified because of its temporal affirmation and

continuity. However, the religious wars in the sixteenth and

seventeenth

centuries not only weakened the natural law but also damaged the

traditional

patterns. The transition, then, not only shifted emphasis from one

source of

law to another, but also weakened both. The church as custodian and

overseer of

natural law was challenged, and the traditional ways of life of the

people from

whose bosom had sprung the common law were disrupted. Under these

circumstances, the leeway of the monarchs to manipulate natural and

common law

constituted paradoxically both a source of abuse and a potential for

order. It

provided for transformation of the nature of the law: instead of being there, as given -- by God or by

tradition -- the law could be made, by

the sovereign.

Sovereignty

and the State

When the religious

wars and the

disruption of the Holy Roman Empire made the European monarchs,

particularly

those of emerging nation-states like England, France and Spain,

increasingly

independent of the Pope and the Emperor as God's overseers, the

question of the

nature of their authority and their position in relation to God's laws

as well

as the laws of the land became acute. The problem was not academic.

Religious

wars had caused disastrous and often inconclusive conflicts which,

while

eliminating many feudal kingdoms and principalities, had also

contributed to

the emergence of bigger entities which could no longer be overrun and

absorbed

by simple conquest. A stalemate of powers was creating new social,

economic,

political, legal and cultural dimensions. The post-Reformation

political

realities were rulers with their divine rights, their people and the

territory

they controlled, in whose context new power/authority complexes evolved.

In France a group of

jurists

and political thinkers known as the Politiques,

including Dumoulin, Loyseau, Bodin and William Barclay (the Scottish

lawyer

living in France), were formulating the philosophical concepts for the

new

political realities. Jean Bodin (1530-1596) in The Six

Bookes of a Commonweale (1576) developed the concept of

sovereignty, the absolute and perpetual power vested in a commonwealth.

Considering the man to whom the people gave absolute power during his

natural

life, he noted, "If such absolute power is given him simply and

unconditionally, and not in virtue of some office or commission, nor in

form of

a revocable grant, the recipient certainly is, and should be

acknowledged to

be, a sovereign."[27] While Bodin subscribed to the current of his

time that "the absolute power of princes and sovereign lords does not

extend to the laws of God and of nature," he reverted to classic Roman

legal concepts in maintaining. that so far as the civil law is

concerned, i.e.,

the law made by the sovereign,

The

prince is above the law, for the word law in

Latin implies the command of him who is invested with sovereign

power .... It follows of necessity that the king cannot be subject to

his own laws, [while] it is clear that the principal mark of sovereign

majesty and

absolute power is the right to impose laws generally on all subjects

regardless

of their consent.[28]

This idea of

sovereignty gives

a ruling body, with effective control over a given population within a

given

territory, the authority to make and administer laws and maintain

order. In its

pure form this legitimization of power into authority on the basis of

sovereignty had a very thin layer of legitimacy. According to Bodin:

If a

sovereign magistrate is given office for one year, or for any other

predetermined period, and continues to exercise the authority bestowed

on him

after the conclusion of his term, he does so either by consent or by

force and

violence. If he does so by force it is manifest tyranny. The tyrant is

a true

sovereign for all that. But if the magistrate continues in office by

consent,

he is not a sovereign prince, seeing that he only exercises power on

sufferance. Still less is he a sovereign if the term of his office is

not

fixed, for in that case he has no more than a precarious commission.[29]

The tendency to

justify strong

sovereign power was not only to maintain law and order within the new

post-Reformation political entities (which we shall identify as

states), but

also to stabilize their precarious coexistence. It implied, at its

origin, two

basic political phenomena checking and balancing their relationships

and

testing their political reality and viability: 1) The equality of these

states

in their dealings with each other: Either because of their balance of

powers or

because of stalemated conjunctures, they could not eliminate or

dislocate each

other and thus had to recognize the exclusive jurisdiction of each

within its

own boundaries. 2) Their independence from outside interference in

making their

laws and governments-a consequence of the first characteristic.

The new sovereigns

were equal

in so far as they could survive the blows of their adversaries, avoid

being

overrun and lose their identity, and enter into covenants and

agreements as

equals able to fulfill them.[30] This implied, in the absence of a superior

authority above the sovereign states, contentions and confrontations

that would

eventually weed out those who were not "sovereign" enough, and

establish a perpetual balance of powers among those who remained

sovereign,

creating rules of conduct which those who recognized each other would

abide by.[31] By the time of the Peace of Westphalia

(1648) which officially ended the religious wars, some six hundred

medieval

political entities had been absorbed by bigger units.

At the beginning of

this

chapter we said that powers combined to recognize an authority over the

areas

of their overlappings, interactions and interpenetrations, implying

their

active involvement. The recognition of the sovereignty of one

independent

political entity by the others was passive, an acknowledgment that it

"stood on its own" and was a "state" with exclusive

jurisdiction over its realm. To achieve such recognition, the sovereign

state

had to be personified legally and be presented and represented among

other

states. This implied, on the one hand, some understanding of legality

among the

sovereign states and, on the other, an internal process for

establishing and

legitimizing the authority that represented the state. The real

criterion for

the mutual recognition of sovereign states was, of course, the

sovereign's

effective control over the people and the territory he claimed, as well

as his

capacity to fulfill his international claims and obligations,

buttressed,