Chapter

10

Power [1]

Political

power grows out of the barrel of a gun.

Mao Ze-Dong

The gun

that does not

have to shoot is more

eloquent

than the gun that has to shoot and

above

all than the gun which has shot.

Salvador

de Madariaga

We began studying

power in

Chapter Two when we examined man's psychological drive to dominate

other people

and things--the drive by which he complements his security with freedom

of

action. Power has been involved whenever we have examined a

relationship and an

interaction. From the child who charms the candy from his mother to the

group

which inculcates its norms into its members, power is being exercised.

And the

traffic is not just one-way. The mother may not give in, and the member

of the

group can both resist inculcation and influence and modify the norms.

Our present discussion

of the

phenomenon of power, then, is the continuation of what we have been

examining

all along. In that vein, the term "power" is all-pervasive, connoting

the omnipotence of God as well as the energy produced by electricity.

As

Merriam put it, there was power long before there was a written word

for it.

But within the pattern developed in the last chapter, even if we may at

times

make analogies between power and certain elemental manifestations, we

will

concentrate on power as the human actualization of socio-political

fermentations and dynamics. Even within that context, power reveals

itself as

pervasive. How could a child's tantalizing charms, a religion's

imposing

admonitions and a group's social pressures all carry ingredients of

power? To

answer that question we will need to see of what power is made.

I. The

Sources of Power

In the last chapter we

discussed man's ability to extract energy from nature, and also to

exploit his

fellow men to that end. These abilities supplement man's original raw

energy,

giving him additional strength. While exploitation needs some brute

physical

force, our above examples show that power does not depend solely on

physical

strength. The child can hardly be said to be twisting its mother's

arm--literally--to obtain her favors. Brute force can, of course, give

its

holder the possibility of control which lasts as long as the holder is

forcefully superior. But its very simplicity and directness make it

vulnerable

and breakable. Naked force can easily be evaluated and analyzed. It is

like a

piece of stone: it holds only by its weight and rigidity, and when it

hits

other rigid phenomena weaker than itself, it breaks them. When it

encounters

superior force, it breaks. It is only a part of the more complex

phenomenon of

power which, in its flexibility, is like a rubber ball or a spring.

Power has

the potentials of adaptation, resistance and pressure. In its encounter

with a

superior but simpler force it does not break; it can contract or

retreat and

withhold its potentials without being irremediably crushed or broken.

In a

favorable position, it can assume the rigidity of steel and strike

back. Power is. Even when it retracts it makes its

pressure felt. The phenomenon that can be squeezed and takes its new

squeezed

shape without being able to return the pressure is not, in our analogy

of

power, a rubber ball or a spring; it is a piece of dough! Power is by the awe of its presence.[2]

In terms of social

politics,

power can draw from different sources. We have already mentioned brute force whose ingredients range from

the physical (muscular) to certain aspects of the

psychological--stubbornness,

fanaticism or even determination. These latter intangible factors are

included

within the concept of force because

when certain character traits such as stubbornness or fanaticism reach

the

point of rigidified behavioral patterns, they become comparable to

brute force.

The propulsion they produce is forceful, rigid and yet, in its

directness,

vulnerable. Of course, as it is for other sources of power, the

evaluation of

force is subjective. While in a power situation the assumption would be

that if

B submits to A's command it is because

B

finds submitting to A more agreeable

than suffering A's force or coercion,

the preference remains relative.[3]

A masochist perceives pain differently than a paranoiac.

The means

at a power's disposal are obviously of great importance. Means

range from primary tools and

weapons near the force end of the spectrum to more subtle factors such

as money

and wealth.[4] By considering means as the

ingredient of power immediately linked with brute

force, we can understand how mans cultural interaction with his

environment,

through manipulation, exploitation and accumulation, can generate the

sources

of power.

The position

from which power is exercised is another crucial factor.

Like force and means, position

can cover

a spectrum going from the simple instance of a strategic location to

complex

social situations.[5] The president of a bank, the governor of a

state, the justice of the peace each holds a position conducive to

power. We

must note, however, that the aspect of the position we are considering

at this

stage is not totally identical with authority. Authority is the

legitimized

dimension of power which we will discuss in the coming chapter. What we

are

presently considering is neither an office nor exactly the right to

power that

it legitimizes but the power potential that a position can provide even

beyond

the framework of its formal authority. The bank president has the

authority to

sign the grant of loans. But he does so mostly on the advice of his

experts. In

performing that function he may be doing no more than a post office

clerk with

the authority to legalize a signature. Beyond that simple signature,

however,

the bank president holds a position which can radiate power. It depends

very

much on the man and the use he makes of the other ingredients at his

disposal

to wield power by exploiting his position. The bank president who

exercises his

duties strictly for the management of the bank and does not use his

position,

for example, in favor of one faction as against another in a conflict

or an

election, is not using it for what could be power ends. Indeed, if he

does not,

he may not last long in his position unless he is there to buffer

contending

powers. We shall examine similar possibilities in our discussion of

authority.

This dynamic concept

of

position leads us to further sources of power. A power may tap its connections with other powers--not just

vertically but also horizontally and diagonally--to strengthen its own

resources. Power A may call on power C

for help in the A/B power relationship and return

equal help to C in another context. Of course, connection and contact are sine

qua non components of a power complex. In

that sense, power is relational and hierarchical. According to Parsons,

"While the structure of economic power is... lineally quantitative,

simply

a matter of more and less, that of

political power is hierarchical that

is, of higher and lower levels. The

greater power is power over the

lesser, not merely more power than

the lesser."[6] This qualification implies relational

comparability. It is not realistic to compare the power of a Soviet

Kolkhose

official in Siberia with that of the Sheikh of Ras el Kheyma or a

banker in La

Paz. But even where relations exist, one power situation may not imply

another.

For instance, it does not necessarily follow that because A

is more powerful than B,

and B is more powerful than C, A

is more powerful than C. The nature

of the relationships may not be comparable, and until A

and C have become

entangled in a power relationship--whether by the intermediary of B or otherwise--we cannot say that A has

power over C. The A/B relationship

may, for example, be professional, while the B/C

relationship may be paternal or conjugal. The assumption,

however, is that where power relations exist, hierarchical imperatives

arise.

Even the lateral mutual help relationship between distinctly autonomous

power

complexes will not always remain on a par and will be subject to the

interplay

of the whole potentials of the components.

Take, for example, A's need to persuade C that the outcome

of their mutual

assistance will benefit both equally. If A

has good power of persuasion, he may draw a picture showing all the

advantages

to C, although in fact, in the long

run, the outcome may profit A more.

This eventuality permits us to generalize and signal out the power of persuasion as yet another

source of power. For persuading B to

do something profitable to A in a

vertical power relationship is also one of the things A

could do instead of using his force, his material means and

position, or his connections.

To persuade implies

the

capacity to influence or to have influence.

Of course, the simple

fact of having influence may not involve a power relationship. To

illustrate

our point, suppose you told your friend in a restaurant that a certain

stock

was likely to rise on the market, and someone next to your table

overheard your

conversation and as a result bought that stock-something he would not

have done

otherwise. You have influenced him but you have not consciously exerted

power

upon him. Like other ingredients of power, only that part of influence

which

becomes effectively related will be part of a power complex.[7]

The influence exerted

on the

eavesdropper in the restaurant will depend on other factors. He may be

influenced by your confident tone--in other words, your self-confidence.

In general terms, self-confidence can be counted

as a source of power. Its impact is evident when combined with other

ingredients: force, means or position used with self-confidence, and

self-confidence as a dimension of the persuasive process. The

influential statement

may have come from a person with charisma,

which can be defined approximately as an inspirational gift. While

charisma may

be a characteristic in its own right, it is seldom separable from the

power of

persuasion and self-confidence. But it may happen that a charismatic

person is

not self-confident or that he inspires rather than persuades. Still in

the

restaurant, we may find that the eavesdropper is influenced by the

speaker's reputation. He may be influenced even by

the reputation of the restaurant. Suppose he is an amateur investor,

lunching

near Wall Street at a restaurant known as the rendezvous of financial

wizards.

Noticing that his neighbor acts like a habitué of the restaurant, he

assumes

the man to be a stock exchange expert and is therefore impressed by his

words.

Reputation is itself a product of the other components of power:

Consider the

possibilities of combining means (money and mass media) with persuasive

techniques (the contents of mass media programs, based on social

psychology) and,

through publicity and propaganda, creating a power image.

All this suggests, in

the human

context, knowledge and knot-how

which, beyond implying

specialized skills, should include the general

capacity to analyze, to evaluate and to draw appropriate conclusions

for action--including

timing and improvisation, as well as organization

and planning. It is this general

capacity that can establish the relative value of the components of

power, even

the intangible ones such as self-confidence and reputation. A power can

combine

and exploit its potentials to extents which may exceed the

possibilities of any

one of the components in isolation. At times action may appear as a

bluff, that

is, if such potentials as courage and

risk-taking are not (as they should

be) considered components of power. In its analysis of possibilities a

power

should relate its power position to another in the context of total

environment. When Churchill asked his chiefs of staff on British

preparedness

to face the Germans, they replied: "Our conclusion is that prima

facie Germany has most of the

cards; but the real test is whether the morale of our fighting

personnel and

civil population will counterbalance the numerical and material

advantages

which Germany enjoys. We believe it will."[8] Later

events proved them right.

A power should be able

to

analyze and evaluate not only its relationship with another power, but

also the

conflicting natures or simply different textures and shades of other

powers in

their relationships. Thus, one power may use different powers against

each

other or combine some against others in situations beneficial to

itself. Great

Britain remained a great power for some three centuries and into the

twentieth

century partly because it successfully played this balancing game in

the

European power complex.[9]

The range of sources

of power

so far presented has moved from the more elemental to the more

cognizant

dimensions. If, in the social context, knowledge, know-how and the

capacity to

analyze, evaluate and draw appropriate conclusions for action are the

essential

sources of power, then by implication knowledge means the power

holder's

knowledge about the power situation. In other words, power should be conscious of its power. To give a simple

illustration, one may say that the water behind a dam is only force.

Before the

dam was built, the downhill flow of the river was naked force; after

the dam is

built, the water it holds is 'tamed force that generates electric

power. But no

power will be produced if the valves of the dam are not opened and the

water is

not permitted to become active. If

there were no turbines and generators behind the valves, the movement

of water

would turn simply into forceful streams. It is in its contact

with the turbines and generators, which put up a relative

resistance but rotate under the pressure of the forceful stream, that

the

latter becomes effective in

generating power. The power holders, however, are those who created the

plus-potential by holding the water

behind the dam and putting it in contact with the generator, and who

decide on

the distribution of electricity. The power they control is the

potential energy

which the high level of water holds behind the dam. Power

can thus be conceptualized as the conscious plus-potential which

is active, in contact and effective.[10]

*

* *

As our discussion of

the

sources of power has unfolded, you may have noticed that these sources

emanate

from the socio-political phenomena we have covered in preceding

chapters. Our

concern is not only the direct and obvious relationship between the

domination

drive and power, but the elemental and yet intricate intertwining of

the

ingredients of power within the sociopolitical flux. If we look

closely, we

see, for example, that it is the combination of force and man's

manipulative

potentials, (considered in Chapter Nine) which can supply the means.

Further,

the general capacity to analyze, evaluate and draw appropriate

conclusions for

action, timing, improvisation, organization, planning and the

consciousness

imperative of power are all, of course, related to the ability to

choose and to

act (and when it is appropriate not to act[11])

within the total environment. But these are elementary connections and

may, if

taken literally, limit our conception of power. We can gain a more

solid grasp

and wider vision of the all-pervading phenomenon of power by looking at

its

relationships with the more or less abstract socio-political phenomena.

Thus,

when we consider such factors as connection, the power of persuasion or

influence,

we have to bear them in mind not simply as individual attributes but as

sources

emanating from and understandable within the framework of group

dynamics and

prevailing value systems as elaborated in our earlier chapters. In that

perspective power is not exclusively nor even significantly the power

of an

individual but a complex whose nucleus may be, for example, an

ideological

movement.[12] While motor personalities, as discussed in

Chapter Three, do play a role (at times crucial) in that context, their

leadership should be envisioned within the complex whole.

II. The

Spheres of Power

To be active, in

contact and

effective, power must mesh with the elements over which it has power.

In the

process of entanglement to gain control, those who seek domineering

positions

may have to confine their freedom. Power can be likened to a pyramid

because at

every stage of the struggle for domination only some of those at the

bottom

should move up, forming the narrow top strata which will dominate and

"sit"

on the lower strata, the wide base of power. But the pyramid of power

is not a

static geometric form. Its dynamics and fermentations require permanent

exercise and affirmation of the powers which shore it.. Within it there

will be

constant contact, relation, interaction, transaction and counteraction

among

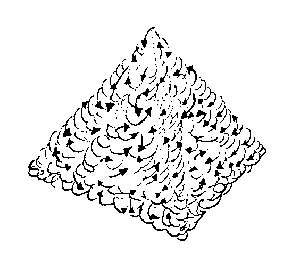

the action complexes which make it a whole (Fig. 10-01).

Fig

10-01

Power, if it is power,

is ever

evolving. We picture it here as a plain pyramid only to simplify our

presentation. Like all other socio-political phenomena, power should

not be

visualized as a solid chunk of concrete but as a flux with every

particle an

interacting factor of the whole. Figuratively speaking, in its dynamics

and

fermentations power should possess the flexibility to transform itself,

whenever appropriate, from extreme weight and rigidity to the

weightlessness of

a light gas. Within any relationship there is an optimum form in which

power,

depending on its texture, functions best. At the rigid extreme it may

exercise

naked force--an effective instrument under certain conditions--while

under

other circumstances it may diffuse and lighten its pressure over its

components

or opponents so that its weight may scarcely be felt, and yet it may

remain in

control.

The top of the pyramid

sits

best, of course, when it can distribute its weight evenly over the

base. In

political terms, this happens when the power exercises equal control

and/or

care over different components of its complex. Depending on its

fluidity, it

may have greater or lesser freedom of action when it shifts its control

and/or

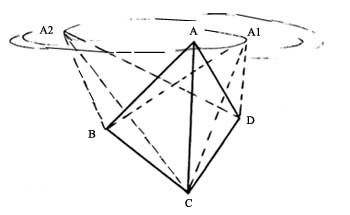

care within a tolerable radius. In position A1 in

Fig. 10-02, the top of the pyramid is distanced from points B

and C of the base and other points along the

connecting lines A1B and A1C as

compared to the A1D line.

Fig.

10-02

A1 either

controls the A1D area of the pyramid

more or

gives it more attention and care. Yet it still seems to be in balance,

because

in its overall situation, its relation to D

compensates its distance from B and C.

In position A2 the

power-holder seems more precarious. It is off balance and may fall. The

shifting of control and emphasis by the summit of the pyramid is, of

course, an

involved process within the different strata of the complex. The point

of

pressure and support may not be uniform from top to bottom. Each point

of

control below the summit may have a greater or lesser radius of

oscillation,

depending on its viscosity. There are, within the complex, "proximate

policy makers," [13]i.e.,

those who exercise or are delegated to exercise power at different

levels and

sectors of the pyramid and thus share the power of the summit (Fig.

10-03).

Fig.

10-03

Again, power is

presented

schematically as a uniform pyramid for the sake of simplicity. For

closer

analysis we may examine a specific section of the pyramid in detail,

making

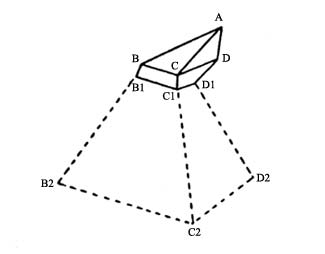

abstraction of the rest. For a concrete example, let us apply our model

to the

last three Democratic presidential campaigns in the U. S. A. We may see

that

the upper strata of Senator Eugene McCarthy's (A) power

complex (Fig. 10-04) in 1968 reveals his great dependence

on "radical" elements (D).

Fig. 10-04

These elements, who

were off

base as far as the Democratic party apparatus was concerned (B1C1D1), contributed to his

failure to win the party's

nomination at the Chicago convention, which was dominated by party

regulars and

union representatives (B and C). In

this limited study, abstraction

is made of the power base, the Democratic voting population of the

United

States (B2C2D2). In

1972, Senator George McGovern won the Democratic party presidential

nomination

because the "radical" elements within the party apparatus had become

substantial enough to override the party regulars and union leaders.

But then

the party went off base as far as the Democratic voting population of

the

country was concerned. In 1976, Jimmy Carter's campaign machinery as

one

component of the Democratic apparatus moved up the pyramid, despite

some

"stop Jimmy Carter" efforts within the party, and won the election

more on its appeal to the popular base rather than by an all-out

Democratic

party campaign.

Power has the

possibility not

only to oscillate within a radius on a plane as in Fig. 10-02, but to

compress

or dilate, thus creating a more compact or expanded relationship among

its

components (see Fig. 10-05).

Fig.

10-05

It may compress when

it needs

better control of a situation or when the components require a closer

relationship to give better cohesion to the whole. The compression may

also

take place at the base and the power-holder may, or may have to,

relinquish

some grounds in order to keep the same angle of power within the

remaining

components; otherwise a compression from the top, without reducing the

surface

of the bottom, will flatten the power-holder's controlling position.

Flattening

implies reduction of power components, such as a reverse process in a

cumulative economy which, if continued to the extreme, could revert to

a

subsistence level where, as we saw in Chapter Three, there will be few

ingredients

for building a substantial power pyramid. The model applies to such a

variety

of instances as the retreat and regrouping of an army, the retrenchment

of a

business, or reduction in the international commitments of a nation.

The dilation may occur

when a

condensation within the complex calls for the easing of power controls.

It may

also be a prelude to an elation of power strata preparing for further

expansion. But an elation without possibilities for expansion at the

base,

distancing the upper-strata of the power complex from the base, may

reduce its

stability. For example, in the 1960's de Gaule played superpower

foreign policy

without adequate means, remaining aloof from certain crucial French

domestic

problems. The result was dissatisfaction and alienation of some sectors

of his

popular base, culminating in the 1968 events and the uprising of the

students.

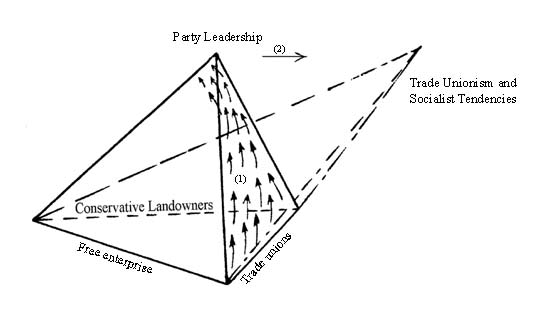

Shifts, compressions or dilations of power create different relationships and ratios within the power complex, upsetting the prevailing habituations, frustrations and expectations, and perhaps eventually changing its nature and course. A party leadership which starts to emphasize workers' rights will eventually embrace more the ideologies of trade unionism and socialism than those of free enterprise and conservative land ownership. The shift may take place because of a prior trade unionist penetration into the party leadership (see Fig. 10-06), or because party policy-makers, although not of trade unionist origin themselves, may have detected favorable grounds among the workers. In the latter case, if the emphasis persists, the party's rank-and-file may gradually be penetrated by trade unionist elements.

Fig.

10-06

In general terms,

growing

emphasis on the role of certain sectors of the power complex may amount

to the

passage of some power potentials to those sectors- a trend which may

not be

reversible and which may eventually change the power relationship

patterns or

even the nature of the power complex. A father who permits his son to

use the family

car, both to make the son more useful in doing family errands and to

give his

son more liberty, will have less control over the car than before. It

will be

difficult to revert to the earlier situation and prohibit his son's use

of the

car without compensation or friction. Similarly, the industrialist who,

after

having run his enterprise on the basis of his individual will and

decision-making, agrees to consider the views of the workers, will have

a hard

time reverting to individual rule. But his recognition of the workers'

views,

although changing the power relationship, may create more interest and

incentive in the workers, increase production, and in the long run give

the

industrialist possibilities of expansion. It has, nevertheless, changed

the power

relationship within the pyramid.

In dilation of a power

complex,

the sum total of control is not reduced but diffused and dispersed

among the

different strata and components of the complex. The

liberalization of the Catholic Church ever since John XXIII

and Paul VI gave new vigor and credibility to the faith, but at the

same time

made open dissent

among the clergy

possible on such matters as birth control. Khrushchev's recognition of

the

possibility of national roads to socialism (which Tito had advocated)

loosened

the lid which Stalin had placed tightly over Eastern Europe. It

resulted in the

uprising in Hungary and later liberalizations in other Eastern European

countries. The Soviet Union had to use force in both Hungary and

Czechoslovakia

to maintain its control and power. In this case the controlled elements

in a

situation of dilation moved towards disintegrating the very power

structure

itself. But in the process of liberalization, the relationship of the

Soviet

Union with the socialist countries of Eastern Europe changed. Even

after

military occupation of Hungary and Czechoslovakia (and in the case of

Rumania,

whose integrity it respected more), the Soviet power did not impose its

total

will on a party and a people which had undertaken a new direction. The

dilation

created by de-Stalinization within the Soviet Union and the socialist

countries

of Eastern Europe diffused to some extent the power which had until

then been

quasi-totally held by the Soviet Union. In exchange, despite its

military interventions,

the Soviet Union gained influence among the Third World countries and

even in

the Western world. One may argue that the Soviet Union would have

gained even

greater influence in other parts of the world had it not used naked

force

against the deviations in Hungary and Czechoslovakia. But timing and

dosage of

the use of power and its dilation or compression are complicated. Had

the

Soviet Union not intervened in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, the

dispersion and

diffusion of power may have had consequences which would have changed

beyond

recognition the very nature of Soviet power. Such alteration could not

have

taken place solely in the relationship and ratio of control within that

power

complex, but also in relation to factors beyond it and potentially

detrimental

to its very existence.

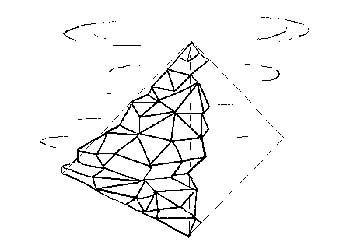

Combining the

different

dimensions of power dynamics as illustrated by pyramidal configurations

in the

last pages, we may, by superimposing Figs. 10-1, 10-02, 10-03 and

10-05,

visualize a power complex as a sphere with the power nucleus at its

center of

gravity (see Fig. 10-07). The power complex thus represented will

resemble the

physical illustration of atomic structures.

Fig.

10-07

Let us remember,

however, that

power within the human context has its complicated laws of fermentation

and

dynamics and is not, with our present knowledge of electronic and

mechanical

phenomena, easily and simply reducible to an illustration of an atom.

Accordingly, if we were to use the atomic model to illustrate it, we

would at

least have to add to it loops, broken lines and zigzags!

If you look closely at Fig. 10-07, you will

notice that some such possibilities have been incorporated, with our

apologies

to the atomic scientists.

But above all, the

point made

earlier about the necessity for contact implies that power, in human

social

terms, is perceivable only in relation to other power complexes. Power,

whether

individual or social, does not operate in

vacuo. In the social context, when a power complex becomes so

close-knit as

to retire into a shell, with the domineering and dominated components

absolutely consumed in their relational circuit, the totality that

ensues

should be taken into account as one entity which may have enclosed

potential

power but which is not realized until it encounters other power

complexes. It

is like a body in good physical and psychological health in which the

kidney

and the nose each perform their functions as part of the whole and do

not

exercise power over each other. In order to exist as power, that body

should

come into contact with its environment, i.e., spheres of other powers.

In a

vacuum it is as good as dead.

Power is a

relationship. It

involves domination and submission. Even in the personal power

relationship

between parents and child, what remains outside that particular complex

is apt

to create other power relations. Beyond the limitations and permissions

of the

parent-child relationship, the child fits into other environmental

situations.

His relationship with his peers or even his imaginary domination of his

toys or

his pet engender attitudes often influencing his behavior in the

parent-child

complex. But this is an extreme example. In the social context power

complexes

operate promiscuously. They often overlap and interpenetrate each other

and, in

their spherical dynamics, conflict, cohabit, compromise or cooperate.

Vacuums

do not remain vacuums. When the United Kingdom, moving to compress its

area of

control after the components of its power had thinned out, announced

its

withdrawal from the east of the Suez Canal, the expanding U. S., U. S.

S. R.

and other local powers prepared to take over.

In the struggle for

domination

and power, the hierarchy of complexes does not organize itself without

clashes,

gropings, repeated encounters, perseverance and challenges. Clashes may

keep

some contenders aloof from each other, in which case no power

relationship is

established between them. The power that can be generated will depend

on the

combination of the domineering and submitting factors and the extent to

which

they fuse and amalgamate. As we examine the relational nature of power,

it

seems that power cannot be conceived alone. It needs at least two

components,

power and its antimony. In the social context the consciousness of

power will

tend to call for the consciousness of the elements over which it has

power.

What is the power which is not challenged? Like Caligula, power may

push its

docile subjects to the brink of revolt in order to feel their

resistance and

thus feel itself.[14]

Power, then, is

conditional to

resistance to such an extent that it cannot be conceived without it. In

the

words of Solzhenitsyn, "You are strong only as long as you don't

deprive

people of everything. For a person

you've taken everything from is no

longer in your power."[15] It follows that the resistance to power may

be external or internal in varying degrees and that in the absence of a

relatively external challenge, in order to substantiate its dynamics,

power

will ferment resistance from within. Indeed, the fermentation for

resistance

should not start only when the comparatively foreign challenge has

ceased; its

germs should be ever present within the power so that power does not

cease to

exist when the external challenge is absent. This existential

relational nature

of power thus implies that resistance is part and parcel of power,

without

which it may collapse or rot. Lord Acton's "Power tends to corrupt and

absolute power corrupts absolutely,"[16]

is not a moral maxim but an empirically conceptualizable statement.

The recognition of

resistance

as a component of power reverts us to such socio-political dimensions

as the

domination drive and its potentials for spiralling into an end in

itself, or

group dynamics with different degrees of integration and possibilities

of overintegration

and disintegration, or, still, the attitude of group members within a

spectrum

from conformity to revolt. In other words, power as the engendered

energy of

culture should not be conceived as a locomotive pulling the train of

culture

along the tracks. Power complexes in their inter- and intradynamics and

fermentations present different degrees of integration and entanglement

which

may at times cancel each other out, leaving a culture with its

internecine

power conflicts having little energy. It is the consciousness of power

complexes within a culture about the potentials of power as the raw

material

for socio-political organization, and the way power components and

complexes

involved in a culture are stratified and their integrative and

competitive potentials

actualized, that gives a culture its impulse. That consciousness is the

strain

within a culture which we shall identify as political culture, the

subject of

our next chapter.