Chapter

7

Value/Norm-Forming

Agencies

and Processes

'Tis

Education forms the common mind,

Just

as

the Twig is Bent, the Tree's inclin'd.

Alexander

Pope

Since

every life experience and every encounter contribute to the formation

of values

and attitudes in the members of society, it is not always easy to

identify

values and attitudes as functions of a particular agency. Above all,

the social

fluid is pregnant with power and flows under the impulse of the

weightier parts

of the society which hold that power -- the power complex itself being

both cause

and consequence of the value system which the forming agencies promote.

The

social complex, in its fermentations and dynamics, embraces agencies

and

institutions and transcends them. Socialization, in its encompassing

connotation, is carried out by the society as a whole. While in this:

chapter

we will concentrate on family, peer group, church, educational system,

ideological parties and mass media as value-forming agencies, they do

not cover

the value-forming process completely. Their study is a logical step

towards

understanding political institutions and structures, which we will

cover in later chapters and which are more

closely related to those normative areas we identified in our last

chapter as

legal.[1]

I.

Family

To discover how

society disseminates its values and

inculcates its members with them, we can perhaps find a

point of

departure in our earlier discussion of values as the content of the

group. We

noticed that there was one group the human being could not do

without--namely,

the immanent group, out of which he emanates. Until the day when

test-tube

babies become the normal method of procreation, we need a man and a

woman to do

the job. Because of this context and the comparatively long period of

weaning

and rearing, the first germs of social behavior are inculcated within

the

family. Physiologically and traditionally, the male-female couple

constitutes

the nucleus.

The family is the

early natural

habitat of the child, and parents are the first likely potentates he

encounters. They ark also the most likely persons with

whom the child will establish his first relationships, which,

though obviously functional, are essentially affectional, providing

bases for

the formation of values. It is therefore understandable that

recognition of the

family's authority and responsibility towards the child has been a

prevalent

social trend throughout human history.[2]

Exceptions to this

general

pattern may occur during abrupt social changes and revolutions, when

the newly

installed power structures may need to alienate the new generations

from the

old for an overhaul of the value system. But then, at least so far in

the

history of mankind, the role of the family as a value-forming agency

has again

been recognized and restored. In recent times, National Socialists in

Germany,

early Soviets and Chinese Communists, among others, have attempted the

systematic alienation of the generations by indoctrinating the young

through

other value-forming agencies (education, the party organization and

mass media)

against the values of their families. The Nazi experience lasted only a

short

while, but its impact was rapid because, as we saw earlier, it promoted

values

based on myths rooted in German folklore and culture. Thus, in the

German

experience, the indoctrination of the younger generations soon pacified

the

older generations and the family could again play a role as

value-forming

agency -- although its influence was reduced by other agencies, as we

shall

discuss later. The Nazis were indoctrinating the younger generation not

so much

against the traditional values of the family as against the more recent

bourgeois and proletarian values and ideologies that had impregnated

large

social segments, rivalizing the Nazi myth.[3]

In the Soviet Union

the need to

counter the traditional values of older segments of the family also

arose,

beyond ideological considerations, for the practical needs of a system

which

had to mobilize the rising generations in a revolutionary economic and

social

outlook. What the Soviet regime had inherited from the Tzar was not a

pre-communist, saturated capitalism, as depicted by Marx, but a

backward,

agricultural and devastated economy. Before learning the ideological

intricacies of Marxism and Leninism, the young generation had to learn

discipline, punctuality and sound working habits. Lenin had said, "Put

a

Muzhik on a tractor and you will have Socialism." To introduce

a Muzhik to a tractor was

not an easy job, but the Soviets were set on accomplishing it. There

was also,

of course, the ideological premise of reducing the role of the

bourgeois

family, which was anathema to the edification of communism. But it was

only the

"bourgeois" dimension of the family-that part which made of the

family an instrument of production and consumption in the

feudal-capitalist

system -- that the Soviets wanted to get rid of. By the early 1930's,

when things

had settled down and the Stalin regime needed a more controllable

social base

on which to operate, the family regained its role as value-forming

agency

within the new Soviet social structure.[4] Here

is how A. S. Makarenko, the Soviet

pedagogue whose A Book for Parents

has been a best-seller in the Soviet Union

for three decades, sees the role of the Soviet family:

The

family becomes the natural primary cell of society, the place where the

delight

of human life is realized, where the triumphant forces of man are

refreshed,

where children -- the chief joy of life -- live and grow.

Our

parents are not without authority either, but this authority is only

the

reflection of social authority. In our country the duty of a father

toward his

children is a particular form of his duty toward society. It is as if

our

society says to parents:

You

have joined together in goodwill and love, rejoice in your children and

expect

to go on rejoicing in them. That is your own personal affair and

concerns your

own personal happiness. But in this happy process you have given birth

to new

people. A time will come when these people will cease to be only a joy

to you and

become independent members of society. It is not at all a matter of

indifference to society what kind of people they will be. In handing

over to

you a certain measure of social authority, the Soviet state demands

from you

correct upbringing of future citizens. Particularly it relies on a

certain

circumstance arising naturally out of your union -- on your parental

love ....

Parental

authority in Soviet society is authority based not only on the

delegated power

of society, but on the whole strength of public morality, which demands

from

parents that at least they should not be morally depraved.[5]

A Soviet decree of

July 8,

1944, dealt with many family matters in bourgeois terms, such as the

illegitimate child, unwed mother or multistage and complicated divorce

procedures. Some futurist communal concepts of the old guard have

lingered,

such as those of economist S. Stroumiline, who recognized that parents

are not

necessarily good educators and that the child, as of the moment when

his

umbilical cord is cut, becomes a subject with rights, whose education

should be

entrusted by the society to gifted and competent educators.[6] But the mainstream of contemporary Soviet

family life is oriented by the basic ideas and goals of the 1944

decree, with a

Victorian puritan morality

idealizing "psychological 'forces of cohesion'; feelings of love, kinship, duty, family solidarity and

responsibility."[7] There is, however, a growing tendency on the

part of Soviet families to transfer an ever greater part of the

responsibility for

child rearing to social institutions. Beyond the ideological

acquiescence that

is increasing among the new generation of parents born and raised after

the

October Revolution, this development is due also to social evolutions

similar

to those in the industrial West after the Victorian Era. Children can

become

time-consuming for ambitious and socially involved parents.[8] The 1977 Constitution of the USSR obliges

Soviet citizens to devote themselves to the upbringing of their

children

(Article 66).

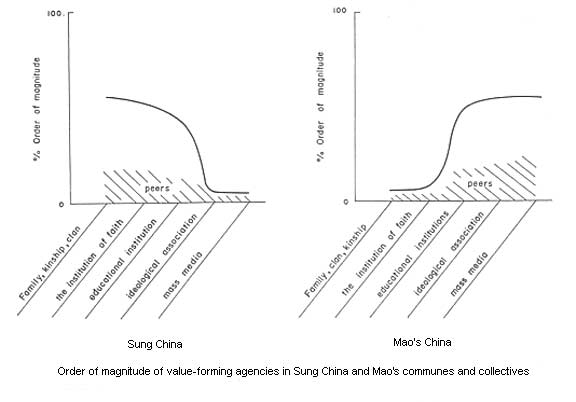

The Chinese experiment

of breaking the traditional

value-forming role of the family presents its own particular features.

We saw

earlier how ancient and deep-rooted filial piety was in China. The

whole of

Chinese traditional culture and Confucian orthodoxy was interwoven with

the

kinship system.[9] Before the advent of the People's Republic

of China, the modernizing elements had already initiated the "family

revolution," notably during the New Culture Movement which started in

1917

and culminated in the May 4th movement of 1919. The general thrust of

the

"family revolution" was to transform the kinship ties and lineage

systems, which were virtually the patterns of social and political

structures,

into a more westernized nuclear family arrangement. The social trend in

this

direction progressed, not always evenly, during the Civil, Japanese and

Second

World Wars. Since 1949 and the installation of the Communist regime,

there have

been variations in the orientation of the Chinese Communist Party

towards the

family. The general direction has been, of course, a systematic

de-emphasis of

the traditional extended family. But the nuclear family itself,

although

recognized as a basic social unit, has at times become the subject of

revolutionary measures, notably during the Great Leap period in the

50's and

the Cultural Revolution of the 60's.[10] In

its variations, the general tendency of

the Chinese Communist Party has been to absorb the nuclear family

within the

commune. Considering the Chinese traditional extended family heritage,

this

policy points to an attempt by the communist authorities to achieve an

interesting metamorphosis.

One may surmise that

the

Chinese have been trying to circumvent the bourgeois nuclear family

phase. The

conversion from clan and kinship to people's communes may in fact be

easier than

first awakening nuclear family consciousness among couples and their

children,

then stripping them of their autonomy and passing the authority to the

commune.

The loyalty to the traditional patriarchal hierarchy is transferred to

the

ideological communal hierarchy with the parents serving as

value-forming agents

for that goal. The process is plausible if, as the Chinese intended,

the

communal organization is made the basic and sole structure of the

society and

"the function of the state will be limited to protecting the country

from

external aggression; and it will play no role internally.”[11] However, the implication that there may be

external aggression makes the likelihood of the final communal

arrangement

remote, because warding off external aggression implies national

institution

and planning which will strain the communes beyond their communal goals

and

make them part of the big whole.

If peace prevailed,

and the

communes were to become the total life experience of their members and

the sole

value-forming agency, they should become relatively small,

well-integrated

entities free from outside servitudes--and therefore without dependence

or

extensive interaction with the outside including a sovereign national

state.

Such a situation would revert us to conditions similar to those of

primeval

groups. In this situation, the revolutionary committees' and commune

managers'

ideological considerations should no longer be dictated from beyond the

commune, but shaped by the interests of their immediate communal

environment,

and their loyalty should be exclusively to the commune whose basic

nature will

become identical with a clan, with the difference that communes and

clans will

be at the opposite ends of the Marxian historical materialism spectrum.

To

follow the development from one to the other, we should indeed start by

identifying the clan as the early and sole value-forming agency

because, as we

noticed earlier, it is not necessarily the male-female couple which

plays the

predominant value-forming role. The family as a social unit has a more

general

connotation. The nuclear family of father, mother and offspring may

become a

dissociable part of a bigger entity: the extended family, itself

extending into

a clan. There, values are part and parcel of the group and the

identification

of the value forming agency poses no problem. The homogeneous and

monolithic

group and its values are a coherent and coincident whole.

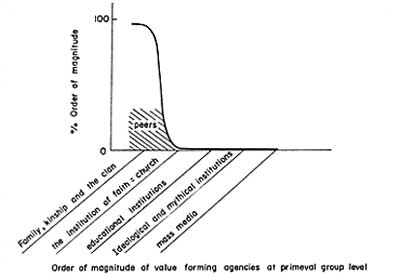

II.

Family and Church

In Chapter Three we

saw that

the evolution of the group brings about differentiations in

specialization and

in social strata, which in turn can bring about diversification of

interests

within the family, clan and kinship pattern, reducing its

all-encompassing

value-forming potentials. The son of the farmer may, for example,

become a

sailor and have life experiences not covered by nor tallying with the

value

pattern the family circle could provide. Thus, as the group grows in

complexity, to remain integrated, it will need additional value-forming

agencies. The agency which seems to have emerged to fulfill the added

value-forming needs at an early stage of social complexity is, in a

broad

sense, the religious institution. It became the promoter of beliefs and

the

custodian of the value system, superimposed on and interacting with the

family

and the clan. The institution of faith grew, of course, out of what was

already

there: the clan. The homo magus, the

witch doctor, the sorcerer, evolved into homo

divinans, the holder of the faith. Different cultures may have

emphasized

either the family or the religious institution as the dominant

value-forming

agency. For example, in China as compared to India the family played a

more

important role than the house of worship. But as anthropological

studies

indicate, at the earlier stages of social evolution, family and

religious

institutions became everywhere the principal value-forming agencies.

What is striking in

this social

evolution is the extent to which the social hierarchy and structure

have

entrusted the inculcation of values to the family and the

institutionalized

belief. Looking back at our earlier discussions, we may trace certain

paths of

convergence leading to this social phenomenon. Among the basic human

drives

discussed in Chapter Two, we can discern variations permitting us to

identify

some of those drives as more material and functional (the physiological

and

biological drives), some as more dynamic (the drives for domination,

excitement, game and challenge) and some as more oriented

towards social rationales (the drives for freedom,

justice and order). Further,

there are some drives which qualify more aptly as affectional and

nonrational.

They are those which complement the physiological needs for contact

comfort or

security and turn into needs for "love," attention, respect,

recognition,

approval and psychic reinforcement. There is also the drive to search

for and

fear the unknown, whose very nature and whose extension beyond the

known leads

to the nonrational. It is the essence of all religion to explain the

inexplicable: creation, death and what lies beyond. We saw in Chapter

Three

that the affectional and the nonrational were dimensions of group

relationship

interacting and merging with functional and rational dimensions to

create and

provide bases for values. It is then understandable to find the

institutions

which envelop and claim these affectional and nonrational dimensions,

namely

family -- clan -- and religion, as the primordial value-forming

agencies. As the

basic texture of the society, they not only perpetuate its value system

but

reflect it. They are not only value-forming agencies but values, and

each

upholds in its teachings the validity of the other. Faith permeates the

family,

and the religious institutions uphold the sacredness of the family and

the

honor of parenthood.

The family, having the

first

natural access to the fresh mind of the child, can generally inculcate

him with

such dimensions necessary for social life as obedience, deference,

cooperation,

"correct" sexual behavior and class consciousness. In most cases, the

family can provide a better evaluation and dosage of reward and

punishment than

can other social institutions. The long weaning and rearing provide the

appropriate setting to exploit the individual's imitative potentials

and to

apply repetitive methods of control and training, inculcating social

symbols

and rituals, feeding and orienting the child's imagination, impulses

and

drives. By appropriate conditioning and reinforcement, by authoritative

yet

affectionate imperatives such as "this is the way to do it," or

"you should not do that," the parents give the child a set of

unquestionable values, the acceptance of which prepares the individual

for

adherence to the belief system and the social and political authority

structure. The family further provides for the child the means of

communication

with his peers, who also play a strong value-forming role because of

their

similitude attraction and kindred qualities.

The complementary

roles and

tendencies of male and female not only lend themselves to satisfying

the

different dimensions of the child's needs, but also provide outlets for

the

adults' drives. Much of the parents' drives for domination, excitement

and

challenge, and their conservative and possessive drives, are combined,

tempered

and channeled for family responsibilities and the benefit of the social

structure. Depending on the culture and the individual nature, the man

may be

more reckless, free from filial and familial bonds. The female may be

socio-psychologically conditioned for motherhood and may develop

conservative

and possessive tendencies out of the biological experience of pregnancy

and

childbirth. The two -- male and female -- once combined, become

predictable and

responsible social units. The social authority structure

recognizes and upholds that responsibility.

The religious

institution picks

up its value-forming role from within the family. Drawing on the

dispositions

developed for acceptance of unquestionable values, it provides the

unanswerable

questions about the beyond with unquestionable answers, on the basis of

which

further values are passed on to the member of society. Devout

conviction

complements filial affection and respect. Belief becomes an important

factor in

the recognition of the peer group, whose adherence to the religious

institution

validates and reinforces its value

structure. As we shall see in Chapter Eleven, belief in divine omnipotence, combined with filial

piety, provides for the acceptance of and submission to the supremacy

of the

social and political hierarchy.

*

*

*

The coherence of the

value-forming roles of family and church with the social structure

depends, of course, on the

homogeneity of the society. That is why we examined the family and the

church

anthropologically at the primeval stage. When the society becomes

heterogeneous, family and religious institutions may be less integrated

within

the social system, in which case they will lose their exclusivity as

value-forming agencies. The social framework will then provide grounds

for the

competition of the different institutions and agencies involved. It

develops

into a complex beyond the original clan where the warriors, the elders

and the

shamans were components directly bound together in kinship ties. If one

of

these components has been instrumental in the group's social evolution

and has

acquired a prominent position in its hierarchy, it will want the

value-forming

agencies to inculcate the social values favoring its prominence, while

the

component itself (the emergent power structure emanating from warriors,

elders

or shamans) will want to operate beyond the confines of those agencies.

Indeed,

it must be able to expand its base of operations if it is to claim

political

sway beyond its own kinship ties; and it should identify itself with

controls and

interests distinct from the power of the custodians of the faith

(unless it is

the custodians of the faith who have secured secular power for

themselves, like

the priests of the Sumerian temples in Mesopotamia some 5,000 years

ago, or the

Church in the Vatican).

The heterogeneous

society will

reduce the functional attributes of the family and make different

demands on

family members. The patriarchal or matriarchal extended family or clan

will no

longer be the group's sole and total identifiable texture. The family,

no

longer the exclusive depository of the group's authority nor the direct

recipient in the distribution of tasks and prerogatives, may itself

feel the

discrepancies of social redistribution. If the parents' expectations

remain

unfulfilled, this may be reflected in the family's value-forming

processes, and

the family may create a spirit of resistance and challenge to the power

structure, providing a basis for social change. If this trend becomes

prevalent, the power structure, to maintain itself, may try to alienate

the

younger generation from the family through other value-forming agencies.

As for the

institutionalized

belief, by virtue of its inherent potentials for control (particularly

over the

soul) it will lay claim to social power. And if it does not already

control the

secular authority; it will rival it. Thus, the belief institution may

form

values not always coinciding with the interests of the political

secular

authority. The Christian church was not conceived by St. Augustine and

St. Thomas

purely and simply to support the ruling system, but also to check on

it. As

history witnesses, this trend has shaped most of our societies up to

the modern

age. From the conflict of Pharaoh Amenophis IV with the priests of

Amon-Re in

1372 B.C., to the Bismarckian Kulturkampf

against the Vatican Council's proclamation of the "dogma of papal

infallibility" in 1870, the issue has remained the same. Thus, with the

society growing in heterogeneity, relationships between the

socio-political

secular powers, the family/clan and the institution of faith evolve,

engendering at times (and often at the same time) cohesion and

coherence or

conflict and rivalry, stimulating the development and diffusion of new

value-forming patterns.

III.

Family, Church and Education

The new value-forming

patterns

in the heterogeneous society evolve from within the old premises. From

within

the family, the clan and the belief institution grows another

value-forming

agency which, sooner or later, can be identified as the instructional

and

educational institution. In its early stages the heterogeneous society

while

creating specializations beyond primeval forms, will nevertheless

depend

greatly on family, clan and kinship to provide training for skills,

crafts and

professions from one generation to another. This functional attribute

of the

family will be different from what it was at the primeval stage, when

the unit

was self-contained and virtually self-sufficient at the subsistence

level.

There, as we saw, every segment of the clan was identical in its

functions with

another segment, with every man, woman and child doing more or less

what every

other man, woman and child did within the clan. In the early cumulative

economy, families diversify their specializations. The carpenter's son

likely

follows his father's profession but has to depend on the butcher for

his meat.

Professional training in this context refers to social functions and at

first

sight may seem to carry no value-forming potentials. We need to take a

closer

look at its evolution, because as it evolves, its value-forming

potentials

become more apparent.

The Apprentice

As the heterogeneous

society

grows more complex, expands and provides greater mobility, weakening

family

ties, especially those of the extended family, the passage of

professional

know-how from one generation to another shifts beyond the family.[12]

Learning a trade, whether from a father or from a master, becomes a

matter of

apprenticeship distinct from the rudimentary experiences and

affectional

securities provided by the family. This shift brings about an identity

among

the members of the same profession which, beyond the functional process

of

professional training, creates a community of outlook and provides for

affectional relationships and value-forming possibilities. At the

traditional

stages such relationships develop into brotherhoods, corporations and

guilds.

While these associations will have different types and degrees of

impact on

their members, they all carry the basic germ of common interests

which, as we noticed in Chapter Four, are essential in

forming social values. In that sense, they provide the historical link

and the

social dimension complementing the tribe and the interest groups. The

guilds of

medieval Europe were not only professional associations but developed

their own

moral codes And norms of conduct. The contracts of indenture passed

between the

master and the parents of the apprentice were not confined to teaching

a craft,

but placed the master in loco parentis--in

the place of the parents. He was responsible both to teach the

apprentice a

skill and to look after his welfare and moral education.[13]

The Scribe and the

Cleric

Parallel to the

evolution of

professional training grows a traditional education centered around the

belief

institutions. The doctors of

faith -- whether doctors because they have evolved from the witch

doctors or

because they promote the "doctrine" -- will be called upon and will

claim to teach the "truth." The truths which the doctors will be

asked to impart will support both practical and moral purposes of

social life.

As distinct from its role as the house of worship, depending on the

complexities of the social structure, the institution of faith

inculcates the

young with the abstract thoughts and moral premises needed for social

order. It

also produces scribes who, by their knowledge of literature and

grammar, by

writing and recording, facilitate commercial business and the business

of

government. This pattern of social evolution varies with different

cultures,

depending upon their particular fermentations and dynamics and the

sequence of

events to which they are exposed in time and space.[14]

In traditional and

agricultural

societies, where change is slow, the economic and technical

specializations are

comparatively few, and most of the population is engaged in farming,

the

possibilities for the propagation of knowledge remain limited. Also,

the number

of people exposed to systematic education is comparatively small and

generally

selective on the bases of filial, professional, belief and class

standards.[15] It is noteworthy that certain social

conditions seem conducive to the growth and autonomy of secular

education as a

distinct value-forming agency, and that without them the secular

education

prematurely instituted tends to gravitate around the more primeval

value-forming agency of religion. For example, while Confucius and

early

Confucians advocated and practiced education free from supernatural

dogma, the

Chinese educational system fell back under the influence of the belief

systems

(although those systems in China were not as centralized, dogmatic and

potent

as medieval Christianity in Europe and did not totally absorb the

secular

educational practices).[16] A later current for systematized secular

education in China during the Sung period (960-1279 A. D.) was more

successful

and longer lasting because China had evolved into a comparatively more

urban

and bourgeois society, with a centralized and bureaucratic government.[17] It was not that the Chinese society was

liberated from religious beliefs, which indeed the Sung also upheld,

but that

concurrent with the premises of belief and the supernatural, the

secular

education acted as a value-forming agency in its own right and provided

moral,

ethical and social standards for a large segment of the Chinese middle

and

upper classes.[18]

In Europe secular

education

developed towards autonomy as a value-forming agency centuries later

than it

did in China. The church's preeminence as a value-forming agency during

the

dark ages of Europe encompassed education and inhibited the advancement

of

scientific learning. Even philosophical thought had to fit the

religious mold.

This religious hegemony was taking place on a continent which had seen

the days

of Aristotle, Plato, Seneca and Cicero. Otherwise, besides the Chinese

experience, in other parts of the world the search for the unknown

generally

combined the justification of the supernatural with philosophical

inquiry,

conditioning the latter by the former.[19] In

Europe, the Christian church became

preponderant because it was in a position to fill the political vacuum

created

by the collapse of the Roman Empire. If the church did continue to

dominate the

European scene for centuries, it was because European social

development and

political conditions were at the level of a traditional culture. We

noticed

earlier that while the social power and authority of the state depended

on the

belief structure, the latter also rivaled the former for social

control. In the

particular case of Europe in the earlier days of the Middle Ages, both

the

Christian religion and the emerging secular power of the northern

barbaric

tribes were alien importations in relation to the Graeco-Roman cultures

of

antiquity. But the church could claim an earlier Roman heritage, thus

commanding the respect of the secular powers it converted to

Christianity.

By the eleventh

century,

however, the secular powers of Europe, having developed their own

identity and

weary of the ever-increasing claims of the popes to temporal as well as

spiritual rule, welcomed conditions that would counterbalance the power

of the

church. These conditions, which culminated after five centuries in the

Renaissance and the Reformation, were economic, social, political and

intellectual, in many ways comparable to those of the Sung period in

China but

with later dramatic technical and industrial consequences catapulting

Europe

into the modern age. Central to our discussion here is the re-emergence

of

philosophical thought beyond the confines of religion, enhancing the

development of educational institutions as autonomous value-forming

agencies.

The early challenge to

the

Christian church's monopoly as value-forming agency took the general

form of

legal contentions and jurisdictional conflicts. A combination of

Germanic Volk laws with Roman law was gradually

being developed and practiced by the secular monarchs, corroding the

ecclesiastic authority.[20] In the spirit of this new revival of

Germanic customs, blended with the pre-Christian Roman legal concepts,

the princes

of the empire came to claim the churches of their realm--their Landeskirche--more and more as an

integral part of their political domain. Their patronage did not stop

at

providing for the material existence of a church but extended to its

administration

and control.[21] In this rivalry for power, the secular had

to meet the challenge of the church, not so much on theological grounds

but in

the field of jurisprudence. Ever increasing numbers of Cardinals were

trained

jurists, equipped with the know-how of government. In a way the state

was

forced to educate itself to cope with the omniscient spiritual power.

The

secular sovereigns thus tended to call more on lawyers and lay civil

servants

than on clerics supplied by the church to fill government offices.

These

bureaucrats had to be trained outside the church. Thus, the University

of

Naples became the first European university to be established by a

royal

charter, instituted by Frederick II in 1224 to train state officials.[22]

The

Philosopher

Parallel to this

evolution, new

dimensions were developing within the church itself. The study of Greek

philosophy, which Europe came to rediscover through Moslem thinkers

like

Avicenna (980-1037) and Averroes (1126-1198), flourished, blending the

theological tenets of such great scholastics as Albertus Magnus

(1193?-1280)

and St. Thomas (1225-1274) with Aristotelian logic. The introduction of

Aristotelian philosophy into theological thinking, however, itself

contributed

to the gradual loosening of the tight jacket of Christian orthodoxy on

philosophic thinking. With the competition between the secular princes

and the

papacy for power and authority, and the new philosophical dimension

injected

into theological thinking, European scholars found greater room for

critical analysis

and learning beyond the teachings of the church. It was within this

enlarged

context that the new thoughts of such scholars as Dante (1265-1321),

Marsiglio

of Padua (1280-1343) and William of Ockham (1290?-1349) gradually

provided

grounds for scientific inquiry, distinguishing the personality of

"educational institutions."[23] The nominalism of William of Ockham reversed

the scholastic synthesis of science and faith of Albertus Magnus and

St. Thomas

and suggested a distinction among philosophy, theology and the

scientific

approach. Basing itself on experimentation and legal positivism, it

carried the

germ of empiricism.[24] By the fourteenth century, most of the

universities that flourished in Germany, although Christian in

orientation and

spirit, had been established by secular princely or city charters,

indicating

the loss of the church's monopoly on education.[25]

The philosophic

emancipation

accompanied other dimensions of social change. The expansion of cities

and

commerce brought about a larger bourgeoisie. The appeal

to laic and non-cleric civil service by the European courts

enlarged the bureaucratic class. Once they became literate, these

classes

called for further literary and

artistic stimulation. The vernacular began to be used in literature. In

France,

Villehardouin (died c. 1212) wrote the first vernacular history, Conquest of Constantinople. The French

romances of the time, such as the Roman de la Rose of William

of Lorris,

taken up by Jean de Meung, were suggestively erotic and bourgeois.

Dante wrote La

Vita Nuova and the Divine Comedy in the Tuscan vernacular,

and he

defended writing in the vernacular in his De Vulgari Eloquentia,

written

in Latin. The attenuation of the church as the dominant pole of

attraction

permitted the development of new perspectives taking into account man's

point

of view. Thus flourished humanists such as the Florentines Petrarch

(1304-1374)

and Boccaccio (13131375). The humanist movement spread rapidly across

Europe

where, particularly in Germany, it developed along with the traditional

teachings within the universities and led the way to pedagogical

studies

concerning the development of the individual, culminating in the strong

plea of

Erasmus (1467-1536) for more schools and the popularization of

education. We know

of the influence that the thoughts of Erasmus had on Luther and the

later

evolutions of the Reformation. It was indeed after the Reformation that

the

educational institutions and philosophic thoughts became substantial

value-forming agencies in Europe. Komensky (or Comenius, 1592-1670),

the Czech

churchman (and nationalist), did for education what Galileo had done

for

astronomy, recognizing the principles of education rather than blind

faith as

man's guide to the labyrinth of the world. All this was accelerated

with the

improvement of the printing press by the early fifteenth century.

However, we must put

in the

right perspective the development of education as a distinct

value-forming

agency in the high middle ages and after. The social currents

contributing to

this development did not, strictly speaking, emanate from the masses

who, we

must remember, remained basically rural. In their refinement, all these

evolutions touched more directly the limited, higher stratum of

European

society. Philosophical inquiry germinated within the church with the

revival of

the Greek classics. In the conjuncture of temporal and spiritual

conflicts, it

found favorable patrons among the aristocrats

and the growing bourgeoisie and bureaucracy who encouraged its

pedagogic orientations

for social purposes. Philosophy begot pedagogy, yet it was the church

that

claimed its spiritual fatherhood, and it was mothered by the secular

powers and

the emerging bourgeoisie and bureaucracy. While the ensuing educational

institutions provided appropriate grounds for philosophical and

scientific

inquiry, they were at the same time regarded as agencies to promote the

interests and values of the various segments concerned. The fact that

these

interests and values did not always coincide was, of course, an

inspiration and

a challenge for philosophy and science. As mentioned earlier, the

church and

the aristocratic rulers did not always see

eye to eye. It was within the centers of higher learning that

the

problem was acknowledged and studied in depth. Despite the small

numbers which

philosophy then touched, it had nevertheless a great impact, for those

it

touched were those who counted. In the following centuries, it was

within

philosophic and scientific circles that the impending conflicts between

aristocracy

and bourgeoisie, proletariat and bourgeoisie, bourgeoisie and

bureaucracy were

first diagnosed.

This process of

philosophic and

scientific inquiry which bases itself on the analysis of facts,

experimentation

and reasoning (in short, the process of thought as opposed to the

uncritical

learning and acceptance of established values) can, of course, carry

germs of

change unfavorable to the dominant and current value system. The

established

social order, or rather its weightier part, can then rightfully resent

and

distrust the unruly and uninhibited tendencies of the intellectuals. In

other

words, within the educational

process we may distinguish two dimensions. The first is one which the prevailing order patronizes

as an extension and elaboration of the value-forming and training by

the

family, the guild and the church; the other, both cause and consequence

of the

first, will be inquiry for further knowledge, to improve life and to

explore

the unexplored. In general terms, this second dimension is

philosophy--the love

of wisdom. The different segments of the prevailing order may use this

dimension as a weapon in their social conflicts, but only in so far as

it

advances their cause. Sometimes the aim may be the total usurpation or

annihilation of the adversary, such as the struggle of the militant

proletariat

against the bourgeoisie. The intelligentsia in this case is given free

course

to pave the road and justify the final victory of the revolution, and

then is

put again into the mold of the ruling order, as in the case of the

Soviet

Union.

Sometimes, however,

the

contending power sectors are symbiotic and use the intelligentsia only

to

redistribute power without endangering each other's existence. This has

been

the usual pattern of social conflicts and the role of the

intelligentsia in the

Western world since the French Revolution. The fine line of social

control over

philosophic and scientific thought and its influence on the course of

events

is, of course, difficult to draw during periods of crisis, and at times

may get

out of the hands of the contending segments of the social order. This

was the

case, for example, of the French Revolution. The influence of the Philosophes had gone beyond what the

"Enlightened Despotism" of Louis XVI had intended and the bourgeoisie

contended. It took the aristocracy, the bourgeoisie and the church

years to

re-establish the simili-order of pre-revolution. But the irreparable

damage had

been done and a new social consciousness had been created, setting the

tone for

the political upheavals of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and

eventually changing the very political texture of European society.

But it is in the

nature of

philosophic and intellectual inquiry, as its historical evolution and

social

dynamics attest, that it can inspire and influence the power structure without becoming it. Love of wisdom, in

its pure state, is not socially functional. It must be patronized by

the

functionally powerful segments of the society to become operative. That

is why

great political thinkers often dedicated their philosophic works to

princes of

state and church--not always to those whose rule corresponded to their

inclinations, but to those whom they hoped to change. And, indeed, they

were

patronized by those who had a hand on the reins of power. Philosophy,

in its

profound essence, does not patronize its own application, and the

socially

effective patron does not philosophize. To the extent that the one does

the

other, he ceases to be the one. To the extent the philosopher-king is a

philosopher, his kingly functions are carried out by others. Asokas do

not

perpetuate themselves,[26]

and the meditations and the practices of Marcus Aurelius were worlds

apart.

The

Pedagogue

I have insisted on the

pure and

essential stages of philosophy because it is there--in the search for

wisdom

(for the love of wisdom)--that philosophy is not socially functional.

Otherwise, the social order does pick up and convert the findings of

philosophic, scientific and intellectual inquiry into practical tools.

Within

the educational institutions, to separate these two dimensions (facts

and

values, skill-training and inquisitiveness, information and

inspiration) and

isolate them from one another is difficult. Once learning in itself is

recognized as a value and the process of learning and inquiry is

initiated,

limits to it must justify themselves within those premises. Education

generates

itself from within by the interaction of the two philosophic and

pedagogic

dimensions and the essential interaction of the peer group. That is

precisely

where the value-forming power of education resides. In abstraction,

that part

of education which is empirical and informative may not be considered

value-forming. But what is empirical and what is informative?

Empiricism itself

may be a principle of behavior and hence become a value. So may the

possession

of information. When the master shows the disciple how to hold the

chisel or

connect the wires or multiply 2 x 2, he not only passes on know-how,

but

commands respect (at least he should), and more often than not he

imparts

values by creating predispositions in the learner to see things from a

particular angle. As for the peer group within the educational

institution, not

only does it have influence through general exposure, but it also

affects the

learning behavior of its members.[27] Both

teachers and students in the

educational environment are led to embrace their peer group standards

of

learning and inquiry.

Educational

institutions thus

become value-forming agencies in their own right, promoting, together

with the

other value-forming agencies, the prevailing social values, but also

contrasting with and influencing them. The teacher receives the impact

of a

family and .a religious, mythical or ideological pattern, but what he

teaches

does not necessarily mirror the values of those institutions. He may

teach the

theory of evolution, conflicting with the dogma of the church, and be

tried for

it, as Scopes experienced in Dayton,

Tennessee, as late as 1925.

IV. New

Churches: Ideological and Mythical Systems

The Scopes trial,

however, was

not only a challenge between the two value-forming agencies of church

and

education. It also engendered a clash of the old and the new in

beliefs, myths

and ideologies. At about the time when the Einstein-Friedmann

relativistic

theories of cosmology--the Big Bang--were elaborated, Clarence Darrow,

the

famous Scopes defense attorney, made William Jennings Bryan, former U.

S.

Secretary of State who had invested all his energies in the

prosecution, testify

in the Dayton court that the whale swallowed Jonah, that Joshua made

the sun

stand still, and that the world was created in the year 4004 B. C.[28] At issue was the cultural evolution of the

Western world since the Renaissance and Reformation.

The inquiry injected

by the

revival of Greek philosophy into theology followed the arduous path

between

curiosity and conformity to reach the conclusions of Copernicus

(1473-1543),

Kepler (1571-1630), Galileo (1564-1642) and beyond, to the rational

thinking of

Descartes (1596-1650). Up to then the Augustinian postulate had

prevailed--believing before understanding. Galileo demonstrated that

what was

believed in, was not necessarily true. Once it was realized that the

premises

of belief may be false, the alternative was to base man's understanding

on

reason.[29] Descartes in France, Hobbes (1588-1679) in

England (although they did not always agree with each other) and others

were

labeled atheists, but Christians were no longer burning heretics at the

stake.

With the philosophic and scientific heritage of the seventeenth

century, the

experimental method initiated by Francis Bacon (1561-1626), the

deductive logic

of Descartes, and Newtonian discoveries based on experimental

rationalism, the

eighteenth century was set to become the Age of Enlightenment. The

rational

observations of the "enlighteners," generally more rational in France

and more observational in England, kept eroding the premises of the

established

church, sometimes inadvertently, other times by design.

Already at the turn of

the

century, John Locke (1632-1704) not only championed the idea of

toleration but,

in his Essay on Human Understanding

(1690), subjecting thought itself to experimentation and observation,

concluded

that ideas originated not in the soul--and by extension God--as

Descartes

believed, but in the senses. This sensualism developed into

eighteenth-century

utilitarianism. Claude Adrien Helvetius (1715-1771), who advanced the

idea that

men were inclined to maximize their pleasures and minimize their pains,

and who

influenced the philosophical work of Bentham, also claimed to have

proved that

God did not exist.[30] Along with French rationalism went David

Hume's (1711-1776) empiricism and skepticism about God[31]

and the flourishing schools of materialism and utilitarianism. Reason

and

empirical observation questioned God. The materialists reduced man's

concerns

to the palpable and "freed" him from abstract and metaphysical

speculations.[32] God was ceasing to be an answer and was

becoming a question. Then what was the answer?

We saw earlier that

religious

institutions appeased man's anxiety and, by inculcating him with faith

in God,

provided him with a sense of purpose which became instrumental in his

elaboration of norms and social and political organization. Since some

process

of value-crystallization is needed to provide man with purpose and

order, when

one value system fails, another should replace it. Reason, while

weakening the

foundations of religious institutions, was providing grounds for

another

value-crystallizing process, namely ideology. Historically, this brings

us to

the distinction we made earlier between the different crystallization

processes. While it was at the end of the nineteenth century that the

term

"ideology" was coined, we must be cautious in assuming that with the

advent of the age of reason in Europe, the belief institutions were

replaced as

value-forming agencies by ideological institutions.

Reason and empiricism

were not

always cozy corners for all the philosophical thinkers of the

eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries. One cannot leave the beyond alone simply because

one

cannot observe it or conceive it by reason.[33] There

grew schools of thought which, not

satisfied with the hard, cold facts of rationalism and not content with

the

pre-rational premises of religious faith, conceived of a beyond which

man could

project, sometimes to irrational dimensions, from within himself: the

abstract

dimensions which could be made godly and willful through feelings and

power of

spirit. The Romantics and idealists saw in man the possibilities of

realizations beyond the dissectable, mechanical and organic man of the

rational

and empirical scientists. Carlyle (1795-1881) saw in man the hero;

Nietzsche

(1844-1900) the superman; and beyond man, Herder (1744-1803) and Fichte

(1762-1814) saw the greatness of the nation; while Hegel, still further

beyond,

conceived of the "Idea of the world mind." These ideas, which

justified breakthroughs beyond the rational restrictions of historical

and philosophical

facts, later inspired the myths for modern value-crystallization, as

discussed

in Chapter Five.

Thus, with the waning

of vigor

in religious institutions--more in some societies, less in others--the

ground

was laid for new value-forming agencies. The process, although rapid in

historical context, was gradual. At first, ideologies such as socialism

or

myths conducive to nationalism did not represent organized institutions

(compared to the degree to which the church was organized). They were

fluids

running through the different social fibers, transmitted by the

existing social

structures: family, educational institutions and peer groups. New

value-forming

agencies based on myths and ideologies emerged in the heterogeneous

modern and

industrialized societies, as did religious institutions based on

supernatural

belief and faith from within the primeval groups when these groups

evolved into

communal and traditional patterns. Neither ideologies and myths, nor

the

institutions inspired by them were exactly new. Communism and socialism

were

outgrowths of capitalism which had itself been preceded by

mercantilism. As for

the institutions which we can identify in general terms as

associations,

pressure groups and parties (which serve to different extents as

value-forming

agencies for myths and ideologies), they were the ever-present

ingredients of

heterogeneous social textures. What was new about them was the

value-forming

magnitude of institutionalized myths and ideologies in the modern

Western

context. That magnitude had different impacts and natures in different

cultural

settings. Nationalism or communism developed differently in Great

Britain,

Germany or Russia.

Up to the end of the

eighteenth

century, the ideologically militant and missionary party was not

developed,

although its ingredients were there. In his essays on parties, David

Hume lists

those which are based on personal

ties, reflecting the affectional dimensions of kinship and friendship,

and

those founded on some real difference

of sentiment or interest, of which the most extraordinary are the

"parties

from principle, especially abstract

speculative principle,...known only to modern times" and, despite their

idealistic claims, often disguising "factions of interest."[34]

Hume had on his mind, notably, the Whigs and the Tories, political

factions

formed in the British Parliament in the seventeenth century,

respectively

opposing and supporting the royal court on questions of principle

which, as we

shall discuss in Chapter Eleven, were also inspired by particular

interests.

But these "parties from principle" were not as yet value-forming

agencies for the indoctrination of the masses. The new philosophic and

scientific approaches were discussed in informed circles which

sometimes became

structured. One of the most cosmopolitan of these was Freemasonry.

Originally a

brotherhood of masons in the middle ages, the organization developed in

England

in the early eighteenth century into a secret society, with

philosophical and

speculative tendencies. Its lodges spread quickly all over Europe where

the new

ideas of change were being studied and discussed. But because of its

secret

nature and lofty ideals, its elaborate symbols and rituals, and the

underdeveloped mass media, the movement was not destined for popular

activism.

Its adherents were mostly members of the upper classes, and--despite

papal

condemnation of the movement--a number of ecclesiastics. Such movements

were

instrumental in acquainting the sovereigns and the ruling classes in

Europe

with emerging ideas and inspiring their reforms and enlightened

despotism.

At the time of the

French

Revolution, the first attempts at organizing militant and ideological

associations and parties were made. Political clubs born of "societies

of

thought" (les sociétés de pensées),

which had been created as of the middle of the eighteenth century in

many

European countries, were meeting in the early years of the French

Revolution to

discuss affairs of state. Among the most militant were the Jacobin

clubs. These

clubs not only discussed political affairs, but watched the authorities

and

debated the reforms and policies of the Constitutional Assembly. The

enthusiasm

of the popular uprising and the liberty enjoyed by the press in the

early years

of the French Revolution supplemented the vigor of the political clubs,

which

did indeed serve as value-forming agencies. The role of these popular

clubs as

controls of the official authorities was recognized by the 1793

Convention, and

by 1794 they served as instruments of "the reign of terror" (the

period when commissioners of the National Convention who were sent to

the

French provinces collaborated with the Jacobins to suppress the

counterrevolutionaries, sometimes with great violence and terrorism).

However, the

experience was not

long-lasting, not only because of the historical conjunctures, but also

because

of the rudimentary techniques and means of mass indoctrination.

Uncompromising

factionalism cloaked in elaborate myths did not fit into the political

culture

of the French Revolution. "The cult of the Supreme Being," the

concept of the "republic of virtue" and the dynamics of "people

in revolution" which Robespierre used for his platform in the Committee

of

Public Safety (Comité de Salut publique)

in 1794 did not provide a well-rounded ideology which the revolutionary

committees and Jacobin clubs supporting him could oppose to their

adversaries,

nor sell to the Paris commune and the French workers as a package.

There was no

centrally organized party or disciplined hierarchy with a declared

ideology to

lead the clubs and the revolutionary committees. Nor were the means and

media

of communication yet developed for the ideological and mythological

agitation

and propaganda. That took the whole of the nineteenth century,

culminating in

the spectacular performances of the Fascist and Nazi parties in the

twentieth

century.

The economic, social

and

technological upheavals of nineteenth-century Europe brought about

conditions

permitting new interest clusters and their convergence towards certain

myths

and ideologies. The concentration of population in industrial centers,

the

development of rail transportation and the improvement of printing

facilitated

the movement of ideas. By the middle of the century the process of

value-crystallization into an ideology representing a certain interest

sector

took recognizable form: that of the Marxian proletariat. The Communist Manifesto defined the

value-forming role of the organs representing different classes and

reserved

for the proletariat, once it took power, the task of educating the

other

classes into the classless society. The politically organized group

thus

supplemented family, church and education as a value-forming agency in

its own

right, heavily depending on the peer group as a point of recruitment

and convergence

of like-minded people.

All politically active

groups,

however, do not have equal claims and impacts as value-forming

agencies. The

value-forming potentials of an organization depend on several systemic

variables. One is the nature of its involvement; that is, whether its

stated

goal is to serve as a forum for a broad spectrum of interests, to

defend

certain interests or to promote particular values. (As discussed in

Chapter

Four, of course, interests and values are intertwined.)[35] Another variable is the extent to which the

group association (or party) claims to voice the views and values of

its

adherents or to form and mold those views and values. Together with

these

variables goes the organization's degree of openness to membership and

participation:

its recruitment policy, the possibilities of member participation in

decision-

and policy-making, and its indoctrinating machinery. The Federation of

British

Industries, the American Farm Bureau Federation or the American

Greyhound Track

Operators Association are not value-forming agencies in the same sense

that the

Communist parties in the Soviet Union and China are. Different

combinations of

the enumerated variables cover, notably, various classifications made

of

political parties.[36] For instance, parties claiming to represent

a broad spectrum and to voice the views and values of their adherents

have been

labeled broker, caucus, coalitional, indirect or mass parties, while

parties

aiming to form and mold their members, promoting particular values,

have been

called ideological, militant, missionary or class interest parties. We

shall

refer to .the activities of these parties within the political system

later,

notably in Chapter Fourteen. As for their value-forming nature,

obviously the

ideologically militant and missionary parties play a more overt role.

But even

associations, organizations and parties claiming only to represent

particular

or broad spectrums of interests have value-forming dimensions. The

trade union

mentality grows within the trade union as distinct from family, church

or

school. The social and political conditions which the existence of

these

organizations brings about, such as voting, campaigning and

electioneering, are

in themselves not only value-forming but also influential on the other

agencies

so far discussed.

The value-forming

potentials of

ideologically and mythically militant associations and parties were not

fully

exploited until they received the boost of modern mass media. Before

that,

propaganda required more initiative on the part of its audience even to

be

transmitted at all. They had to read the pamphlet or move themselves to

within

the limited range of the herald's, bard's, minstrel's or haranguer's

voice. In

the 1920's and 1930 's radio invaded the masses. Through its waves the

modern

political leader could move millions in the comfort of their homes.

V. Mass

Media

Signs and symbols,

words and

images, spoken, written or acted out, whether in personal contacts, in

conferences, or in books, newspapers, magazines, radio or television

serve in

different degrees as instruments and amplifiers of the value-forming

agencies

so far discussed. The medium used by the family is, nearly exclusively,

word of

mouth. The church has traditionally used word of mouth for the masses

and the

written word for its inner communication, with recent experiments using

radio

and TV. The educational establishment has emphasized the written word

and word

of mouth in that order; it has begun to use radio and TV recently and

may use

them more in the future. Political associations and parties use all

these media

but, depending on their environment, rely more and more on radio and

TV--more

on radio in the less developed countries, more on TV in the developed

countries. The choice as to which medium to emphasize thus has

something to do

with the nature of the value-forming agency. The extent to which the

media are

used of course, has also to do with the particular cultures,

particularly

political cultures. In a totalitarian regime with an ideologically or

mythically militant party in power, the media and their contents will

be

declared an extension of the political organization. The program of the

All-Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of March, 1919, provided for

"development of the propaganda of Communist ideas on a wide scale and

for

that purpose the utilization of state resources and apparatus," which

meant, of course, control of the mass media. Under more fluid regimes,

the

contents of the mass media are not directly controlled by the state or

a party.

The media are left more or less open to reflect the different currents

within

the society. In countries like France and Great Britain, the government

controls and subsidizes the functioning of some of the media, such as

radio and

TV, but leaves control of their content to bodies more or less

independent of

direct, overt governmental control. In the United States, while the

media are

promoted as private enterprises, they are subject to certain laws, like

Section

315 of the Federal Communications Act of 1934 providing for equal time

for all

political platforms. Also, state and federal censorship and other

mechanisms

regulate some of their content.

So far we are assuming

that the

medium is only the medium, that the different media are simply channels

serving

the value-forming agencies we have discussed. This is obviously

simplistic. As

pointed out at the beginning of this chapter, the social, political,

economic,

cultural (ethical and aesthetic) flux of the society means values are

formed by

more than just the easily identifiable agencies. The media, then, are

also

media for transmitting these complex dimensions. The poet, the singer,

the

painter or the architect, though using the media, may not represent any

of the

agencies we have so far discussed. But even in a face-to-face, word of

mouth

situation in a family, the language and words used, the intonation of

the

voice--not always voluntarily and consciously--influence the

value-forming

processes. In other words, the medium influences the message. To what

extent

does it do so? McLuhan raised a good deal of controversy by affirming,

"The medium is the message."[37] Let us more moderately say, however, that

there are both the medium and the

message.

One way of

establishing the

media's impact as value-forming agencies is to compare their relative

importance in that role. Depending on their type and nature, the media

have

different impacts, ranges and audiences; some are more appropriate for

some

contents than others. John Crosby, then TV and radio critic for the New

York Herald-Tribune, remarked on the

relativity of the media in regard to the 1960 Kennedy-Nixon

presidential

debate.[38] At the time of the debate, he had listened

to the radio and felt that Nixon had scored better. He was surprised to

find

out the next day that the consensus favored Kennedy. A few days later

he viewed

the videotape of the debate and was amazed at how the TV advantaged

Kennedy.[39] The discrepancy in his judgment of Nixon's

and Kennedy's performances had to do with the additional visual

dimension of

the TV; Kennedy simply looked better. The TV debate had a significant

effect on

the electorate because by 1960 the television had become a mass

medium. The Kennedy-Nixon debate was viewed and commented upon

by a substantial sector of the voting population. The TV became a mass

medium

not only because of technological developments, but also because of its

appeal

to the public and the nature of the country's economy. Books, magazines

and

newspapers have long benefited from technological advances in printing,

but

they demand more concentration and effort on the part of their

audiences. A

greater percentage of the public is likely to be reached by radio and

TV

because the effort demanded for exposure is merely to turn a knob.[40] Had Nixon and Kennedy carried out their

polemics by articles in The Nation,

for example, even if there were greater discrepancy in the scores of

their

duel, it would have touched a different audience and not affected the

outcome

of the elections to the same degree as their TV debate.

The popular use of a

medium

also has to do with a country's economic and social development. The

American

general public, though literate, may not necessarily read as much as

the

general public in, for example, Sweden. According to the 1972

statistics, there

were 333 TV sets per 1000 population in Sweden as against 472 sets per

1000 in

the U. S. A. There were 515 copies of daily newspapers per 1000 in

Sweden as

against 314 in the U. S. A. Of course, the number of newspaper copies

is not a

decisive indicator about the influence of the newspaper as a medium of

information. I have seen the Indian villager read the newspaper front

to back,

and the Manhattanite rush out of the subway, buy the New

York Times, keep the classified section and throw the rest away.

The Western man's culture of accelerated and concentrated economic

effort,

whether in an office, in a factory or on a farm, may reduce his drive

for

concentrated reading.

Because of their

different

forms and potentials, one medium cannot totally replace another. They

appeal to

different audiences with different interests, goals and values. The man

who

wants to know Kantian philosophy will probably want to read it

directly, not

just see a program about it on TV. The written word, depending, of

course, on

whether it is in a popular magazine or a scholarly treatise, can deal

with a

subject in greater detail and be scrutinized more carefully by the

reader than

can TV or radio coverage of the same topic. The book is a docile

companion, yet

a stubborn interlocutor. It is the garden of dreams and the field of

imagination. The reader can make the world of the book according to his

own

image. He can choose his pace with the book, go back to its earlier

arguments

and debate with it. The book will not raise its voice, but neither will

it

change its mind -- printed black on white.

This brings us to our

more

direct concern about the value-forming role of the media. Our

examination of

the different impacts and audiences of the media so far shows us that

their

value-forming potentials vary, but it does not necessarily qualify them

as

value-forming agencies. Rather, at this stage of our inquiry, their

participation in the value-forming process seems to be passive. Indeed,

the

question to ask is: How does a writer come to write what he writes, who

decides

on the content of a book or a radio or TV program, and who wants it?

Who

decides that an article or book should be published or a program go on

the air?

Should we consider mass media as value-forming agencies while they are

really

just frames to be filled by people whose values have been shaped by

other

agencies? After all, Kennedy and Nixon were representing

the political values of their parties.

The mass media's

passivity in

forming values may best be illustrated in the totalitarian state, where

the

media are totally at the service of the political apparatus.

Paradoxically,

however, this same illustration can help us examine the independent

value-forming potentials of the media. For where the fiction of freedom

of

expression is officially subordinated to a myth or ideology, any

discrepancy

which may be discerned between the official structural

and overall content control of the media, and the actual

processing and presentation of the content, will indicate the

possibilities for

the mass media to play an original role in influencing their audience.

In

speaking of the mass media as shapers of values, let us then

distinguish among

structural control, overall content

control, and the actual processing

and presentation of the content.

Structural control of

the

media, reflecting the prevailing social, economic and political order,

can run

from total state control to regulated private enterprise management of

the

media. Total state control is structurally effective only to the extent

that

the total control of the social complex as a whole is effective. The

Soviet

state control of the media during the Stalin era was much more

monolithic than

after de-Stalinization in the early 1960's

when, while the media structures remained under state control, the

"liberals" managed to penetrate the cultural apparatus.[41] It is unthinkable that a Yevtushenko could

have recited "Babi Yar" in front of Stalin and gotten away with it,[42]

or that the outspoken Solzhenitsyn would have been spared from exile

for so

long under the old dictator, or that the "Samizdat"

(personally circulated pamphlets) could proliferate

in the Soviet Union as has been the case recently. Certain media, of

course,

because of their nature and technology, can be controlled more

effectively by a

faction in power. It is more difficult at present to transmit a

clandestine TV

program than to circulate an underground pamphlet.

When we look at the

structural

control of the media in the United States as compared to the

totalitarian

control in the Soviet Union, we notice that the basic democratic

liberties of

freedom of expression, of speech and of the press are conditioned by

the

realities of competitive free enterprise with its tendencies towards

conglomerates and monopolies. A newspaper, a radio or TV network under

competitive free enterprise abides by the same financial and economic

rules

that govern business: it needs a market and a profit. Thus, it must

have either

a sufficiently big organization to gather the information and sell

advertisements,