Chapter

5

Crystallization

of Values

Ah, a man’s reach should exceed

his grasp

or what’s a heaven for?

Robert

Browning

So far we have

discussed

beliefs, myths and ideologies, among other dimensions of values. Now we

will

look at these same phenomena under a new light and from a different

angle, with

more emphasis on the value system characteristics.

To be significant in the social context, values cannot be a haphazard

collection of affectional behaviors, but a coherent system with

hierarchy and

order. Only then can they be identified, dealt with or opposed by other

values

and other value systems.

We frequently refer to

value

systems by different terms, such as beliefs, myths or ideologies, which

are

often used interchangeably.[1] I do not propose a strict separation of

these terms. All three and many others, such as religion, faith,

superstition,

mana, taboo, conviction or confession, lend themselves only with

difficulty to

rigid definitions, not only because of their indiscriminate

application, but

also because of their opinionated usage. One man’s religious belief or

ideological conviction is another’s myth. Those who believe in the

religious

experience of man label ideologies “secular religions” or, depending on

their

interpretation of the particular ideologies, “pseudo religions of

totalitarianism.”[2] The term “myth” has more generally covered a

wide spectrum from beliefs to ideologies, not only as a consequence of

opinionated usage of the term across semantic borders, but also because

the

more pragmatic and empirical tendencies require that affirmations

beyond

scientific inquiry be treated as myths. For our political analysis,

however,

scrutiny of the different processes by which a society crystallizes

values can

prepare the grounds for later inquiries into the mechanism of

government and

conversion of power into authority. For example, we will be able to see

the

relationship between natural law and the divine right of kings, between

the

German Pflichterfullung and Hitler’s

Fuhrer system of government, or between the dictatorship of the

proletariat and

Communist Party leadership and hegemony. Of course, even a gross

delineation of

beliefs, myths and ideologies will not be free from value

judgments-scientific

or otherwise. But while our examples are undoubtedly subject to our

prejudices,

our study can reveal different mechanisms which make values socially

operative.

I.

Beliefs

We are using “belief”

to cover,

grosso modo, religious experience,

superstition, taboo, confession and supernatural faith: the infinite,

the

ultimate, the absolute, the beyond. It includes, then, mythological

divinities

in the supernatural sense which are not to be confused with the concept

of myth

to be discussed later. Sometimes the term “belief” has been coupled

with

“opinion.”[3] The distinction we make here is that beliefs

are the basis of opinions.

We have already

mentioned the

religious beliefs by which values are made socially operative. For

example,

man’s need for transcendental premises in both primeval and more

complex

societies is developed into anthropomorphic and metaphysical beliefs

that help

to validate social rules and structures. The totem pole, the

mythological

divinities and the almighty power of a religion crystallize values into

social

“oughtness.” These transcendental premises refer to a concept of the

holy which

is admittedly related to the unknown. It is in that sense—the

Augustinian sense

of believing prior to understanding—that we use “belief.”

Men do not always use

their

capacities to connect cause and effect, to store knowledge, or to

memorize

experience rationally within the limits of the known. Their inferences

about

phenomena carry them beyond their knowledge and their possibilities for

factual

research. There are effects whose causes escape human understanding.

But men

want to know the unknown—in order to appease their fear and curiosity.

So when

a number of inferences from observable facts point them beyond their

reach,

they may surmise an area of concordance and convergence beyond the

sphere of

their knowledge or understanding. The “beyond” eventually turns into an

assumed

fact, itself the fruit of an inductive process. Once fixed as an

assumption, it

becomes the source of deductions. For example, primeval men will

relate,

through their observations and experiences, crops to water, water to

rain, rain

to wind; and then, not knowing about the source of natural phenomena,

they may

attribute conscious behavior—a spirit—to the wind, conceiving it

according to

their own image—anthropomorphically. On that basis they may also

connect

certain coincidental actions or circumstances to the changes in the

moods and

humor of the spirit. Then, when the wind does not blow the

rain-pregnant

clouds, they will appeal to its spirit. They will try to appease the

“beyond”

according to their understanding of its likes and dislikes as

manifested in the

coincidence of events. For example, if visiting certain places or

performing

certain acts coincides with the wind’s bringing rain, they will, in the

belief

that they are pleasing the spirit, visit the places and perform the

acts

ritually every time they need rain. They may also have to appease or

“buy” the

deity through offerings. The deity created according to man’s image

will have a

value scale similar to man’s.[4] As the deity becomes more important, men

will sacrifice to him their more valuable possessions—calf, lamb, son

or even

themselves. The more this process of god-building is contemplative, the

more

abstract and metaphysical will the deity become. Men will dedicate and

sacrifice to him their souls.

This affectional and

nonrational process is, as discussed earlier, one of man’s basic

drives. It is

a dimension within men which needs fulfillment beyond observable facts,

a

proposition which may set the limits of the dimension at infinity or,

as Hume

would say:

Let men

be once fully persuaded of these two principles that

there is nothing in any object, considered in itself, which can afford

us a

reason for drawing a conclusion beyond it; and, that even after the

observation

of the frequent or constant conjunction of objects, we have no reason

to draw

any inference concerning any object beyond those of which we have had

experience: I say, let men be once fully

convinced of these two principles, and this will throw them so loose

from all

common systems, that they will make no difficulty of receiving any

which may appear

most extraordinary.[5]

Belief is an article

of faith.

Beyond being nonrational, it should be what James identified as living,

forced

(I would rather say forceful) and momentous.[6] It should

sit deep and vibrate the sensitive

cords of man-therefore be living; it should be forced or forceful in

that it

offers only a one-way gain—to believe in its truth as the answer to the

unknown; and finally it should be momentous in its ultimate and yet

immanent

impacts and impressions. Of course, different degrees of these

conditions will

be involved in different beliefs and within different believers. The

example

James gives us, that an appeal to a Christian to believe in Mahdi will

leave

him cold because it is a dead hypothesis within the Christian context,

shows the

relativity of religious beliefs.[7] To embrace

a belief does not necessarily

imply unconscious surrender. A belief may serve as a conscious

projection

beyond the confines of understanding—what may be called conscious

religiousness. Pascal, whose precocious scientific genius amazed the

scientists

of his time, became an ascetic mystic. His words of early

existentialism, which

I would like to quote at some length, best indicate this kind of

religious

experience:

Let

man, then, contemplate entire nature in her height and full majesty;

let him

remove his view from the low objects which surround him; let him regard

that

shining luminary placed as an eternal lamp to give light to the

universe; let

him consider the earth as a point, in comparison with the vast circuit

described by that star [sun]; let him learn with wonder that this vast

circuit

itself is but a very minute point when compared with that embraced by

the stars

which roll in the firmament. But if our view stops there, let the

imagination

pass beyond: it will sooner be wearied with conceiving than nature with

supplying food for contemplation. All this visible world is but an

imperceptible point in the ample bosom of nature. No idea approaches

it. In

vain we extend our conceptions beyond imaginable spaces: we bring forth

but

atoms, in comparison with the reality of things. It is an infinite

sphere, of

which the centre is everywhere, the circumference nowhere. In fine, it

is the

greatest discernible character of the omnipotence of God, that our

imagination

loses itself in this thought.

Let

man, having returned to himself, consider what he is compared to what

is; let

him regard himself as a wanderer into this remote province of nature;

and let

him, from this narrow prison wherein he finds himself dwelling (I mean

the

universe), learn to estimate the earth, kingdoms, cities, and himself,

at a

proper value.

What is

man in the midst of the infinite? But to show him another prodigy

equally

astonishing, let him seek in what he knows things the most minute; let

a mite

exhibit to him in the exceeding smallness of its body, parts

incomparably

smaller, limbs with joints, veins in these limbs, blood in these veins,

humors

in this blood, globules in these humors, gases in these globules; let

him,

still dividing these last objects, exhaust his powers of conception,

and let

the ultimate object at which he can arrive now be the subject of our

discourse;

he will think, perhaps, that this is the minutest atom of nature. I

will show

him therein a new abyss. I will picture to him not only the visible

universe,

but the conceivable immensity of nature, in the compass of this

abbreviation of

an atom. Let him view therein an infinity of worlds, each of which has

its

firmament, its planets, its earth, in the same proportion as the

visible world;

and on this earth animals, and in fine mites, in which he will find

again what

the first have given; and still finding in the others the same thing,

without

end, and without repose, let him lose himself in these wonders, as

astonishing

in their littleness as the others in their magnitude; for who will not

marvel

that our body, which just before was not perceptible in the universe,

itself

imperceptible in the bosom of the all, is now a colossus, a world, or

rather an

act, in comparison with the nothingness at which it is impossible to

arrive?

Whoever

shall thus consider himself, will be frightened at himself and

observing

himself suspended in the mass of matter allotted to him by nature,

between

these two abysses of infinity and nothingness, will tremble at the

sight of

these wonders; and I believe that, his curiosity being changed into

admiration,

he will be more disposed to contemplate them in silence, than to

investigate

them with presumption.

For, in

fine, what is man in the midst of nature? A nothing in comparison with

the

infinite, an all in comparison with nothingness: a mean between nothing

and

all. Infinitely far from comprehending the extremes, the end of things

and

their principle are for him inevitably concealed in an impenetrable

secret;

equally incapable of seeing the nothingness whence he is derived, and

the

infinity in which he is swallowed up.

What

can he do, then, but perceive some appearance in the midst of things,

in

eternal despair of knowing either their principle or their end? All

things have

sprung from nothingness, and are carried onward to the infinite. Who

shall

follow this astonishing procession of things? The Author of these

wonders

comprehends them; no other can.[8]

The premises of

religious and

supernatural beliefs can be based, then, on man’s cognitive awe of

nature.

It is not, however,

the sage’s

or the mystic’s religious experience, which is personal and

untransferable,

that makes values socially operative. Rather, whatever is understood of

the

sage’s experience is molded and reinterpreted within the framework of a

belief,

and elaborated into a value system which supports the social structure

and

safeguards the various spheres of interest. The mystiques of Buddha and

Jesus

were adapted to social needs by their immediate apostles, and the

Buddhist and

Christian societies evolved with little relevance to the original

experiences

of their saints.[9] Pascal also elaborated his “Religious Wager”

to provide the flock of common men grounds to be faithful to the

church. This

“Religious Wager” amounts to an exhortation to play on the winning side

in the

gamble of belief and disbelief. (For you have nothing to lose if you

believe.

Therefore believe,)[10] The wager is obviously a social tool which

may not always be interpreted by the religious establishment in the

light of

Pascal’s earlier sublime preoccupations.

Beliefs, religious and

superstitious, are then social dimensions of man’s inner drives to

search and

fear the unknown. Addressed mainly to the affectional and nonrational

dimensions of man’s behavioral pattern, the supernatural appeal helps

crystallize values to regulate the social functional structures. The

following

passages quoted by Berelson and Steiner make the point better than a

long

discourse on my part.[11] I reproduce them in a sequence that

emphasizes an evolution from primeval to complex societies:

An

agricultural people inhabiting a cool and arid region needs, above all

things,

warmth and rain for the growth of its crops. It is understandable,

consequently, that the Hopi should worship a Sky God who brings rain,

an Earth

Goddess who nourishes the seed, and a Sun God who matures the crops, as

well as

a special Corn Mother and a God of Growth or Germination.[12]

In

ancient Egypt,...in the very early period, there were numerous deities,

many of

which were local gods, or patrons of little kingdoms. As the political

unification of Egypt progressed, a few of the greater gods emerged as

national

deities. As the nation became more and more integrated under the rule

of a powerful

single head, there was a tendency for one god to become supreme. [Thus]

the

ascendance of Re, the sun-god.[13]

A

specifically bourgeois economic ethic had grown up. With the

consciousness of

standing in the fullness of God’s grace and being visibly blessed by

Him, the

bourgeois businessman, as long as he remained within the bounds of

formal

correctness, as long as his moral conduct was spotless and the use to

which he

put his wealth was not objectionable, could follow his pecuniary

interests as

he would and feel that he was fulfilling a duty in doing so. The power

of

religious asceticism provided him in addition with sober,

conscientious, and

unusually industrious workmen, who clung to their work as to -a life

purpose

willed by God.[14]

We find

in religious philosophy a reflection of the real world; the theology of

a

people will echo a dominant note in their terrestrial mode of life. A

pastoral

culture may find its image in a Good Shepherd and his flock; an era of

cathedral building sees God as a Great Architect; an age of commerce

finds Him

with a ledger, jotting down moral debits and credits; emphasis upon the

profit

system and the high-pressure salesmanship that is required to make it

function,

picture Jesus as a super-salesman; and, in an age of science, God “is a

god of

law and order.”[15]

In a later chapter we

shall

examine the process by which beliefs and social and political

structures

transact and draw on each other.

II.

Myths

It is not necessary to

instill

values into anthropomorphic or metaphysical beliefs. Besides, in the

modern

world of technology and scientism, it is difficult to do so. Mythology

does not

always need Krishna or Zeus because the basic premises for

value-crystallization are not always godheads, but the vibrations of

man’s

nonrational and affectional cords. In order to become a myth, an

explanation of

phenomena has to go beyond the rational and the logical and provide an

interpretation appealing to the nonrational dimension.

As we said earlier,

the term

“myth” has a general usage covering whatever relates to the

nonrational. This

broad application, overflowing other terms relating to value systems,

somehow

obscures the treatment and definition of myth in its own right.

Although not

exactly synonymous, myth and belief have the contiguous zone of

mythological

divinities. On the other hand, a myth does not emanate from the

systematic

rationalizations which are usually the origins of ideologies. Yet two

modern

political value-crystallization processes, Fascism and National

Socialism, are nearly

always classified as ideologies despite having the main characteristics

of what

we can, in the narrow sense, identify as myth.[16]

A myth is based on the

folklore

of a people. Folklore as the reflection of a way of life, customs and

traditions can, under specific circumstances, provide for consolidation

of

group identity and, by receiving emphasis, be turned into a myth. As

Pareto

extensively elaborated, a myth is the deformation of historical and

philosophical f acts.[17] It is not, however, a deformation which

remains factual. It has the attracting and orienting power and field we

attributed to values in the last chapter. In the words of Erik Erikson:

A myth,

old or modern, is not a lie. It is useless to try to show that it has

no basis

in fact; nor to claim that its fiction is fake and nonsense. A myth

blends

historical fact and significant fiction in such a way that it ‘rings

true’ to

an area or an era, causing pious wonderment and burning ambition.[18]

The myth-builders

share some of

the fervor of the preachers and some of the certainties of the

ideologues. As

Cassirer argues, “In mythical imagination there is always implied an

act of belief. Without the belief in the

reality of its object, myth would lose its grounds”; and further, “it

seems to

be possible and even indispensable to compare mythical with scientific

thought.”[19] Those who take part in the elaboration of

myths cannot, however, be totally unaware of the distortion of facts in

which

they are involved.

Some indeed have

deliberately

used “myth” to define their particular style of value-system building.

Sorel,

for example, elaborated a myth of action for syndical socialists. This

myth was

to be based on a partisan and simplified presentation of historical

facts and a

utopian image of the future in order to move the masses. As a myth,

this future

image need not be achieved, but it should generate the force of

conviction in

its followers by magnifying and canalizing their feelings, tendencies

and

enthusiasm.[20]

The

significance of Sorel’s concept was its emphasis on action, which is,

in the

last analysis, the decisive factor for the existence and efficacy of a

myth.

Deformation of philosophical and historical facts does not necessarily

bring

about a myth unless the deformed facts ride on action. Without this

dynamism,

in so far as they are deformations of facts, myths either fall apart

and are

discredited or recede into folklore and mythology. To quote Cassirer

again,

“Myth is not a system of dogmatic creeds. It consists much more in

actions than

in mere images or representations.”[21]

Although Sorel himself was more of a classical anarchist, his myth of

action

later served the myth-building purposes of Italian Fascism.

Fascism

Although Fascism may,

as

statecraft, qualify as an ideology because of its rationale on the

pre-eminence

of the state, it has a stronger mythical dimension. Mussolini stated

that he

had no specific doctrine but that of action.[22] In the

particular conjuncture in which the

Fascist movement found itself after World War I, Mussolini’s will to

power

could not be satisfied with and did not need an ideology or a belief.

Italy was

already full of them. Another ideology or a new religion?--it would

have been

just another shade in the spectrum of choices. Besides, the fact that a

respected philosopher like Croce could find Fascism harmless because it

was

devoid of a doctrine was a great asset for Mussolini, helping him to

attract

allies of various beliefs and ideologies and making few enemies at the

outset.

All the political factions and parties contending for power were

counting on

using the Fascists for their different ends, assuming that the

Fascists’ lack

of a solid political platform would make them both useful and easily

disposable. So Mussolini was building something else: a myth—a myth of

action.

But a myth based on action, to spur a movement, should not only provide

a plan

for the action it preaches, but also find means for action. Mussolini

was not

unaware of this. He made action pivotal, but it was to be complemented

by

factual deformations, according to the circumstances. In August 1921,

in a

letter to Michele Bianchi, he wrote:

If

Fascism does not wish to die or, worse still, commit suicide, it must

now

provide itself with a doctrine. Yet this shall not and must not be a

robe of

Nessus clinging to us for all eternity, for tomorrow is something

mysterious

and unforeseen ....I do wish that during the two months which are still

to

elapse before our National Assembly meets, the philosophy of Fascism

could be

created ....

The new

course taken by Fascist activity will in no way diminish the fighting

spirit

typical of Fascism ....Fascism takes for its own the twofold device of

Mazzini:

“Thought and Action.”[23]

Mussolini, while

recognizing

the need for a doctrine, immediately made clear that he did not want

one which

would cling to him for eternity. As was reflected throughout his

political

career, he preferred to supply his myth of action with doctrines which

corresponded to situations as they arose. Philosophy itself, with which

he

wanted to arm Fascism, was needed only when issues did not lend

themselves to

action. The year after his letter to Bianchi, in the train which was

taking him

to Rome to become prime minister, he exclaimed, “Action has dug a grave

for

philosophy.”[24] On October 24, 1922, he stated: “Our myth is

the nation, our myth is the greatness of the nation.”[25] That was seven days before he was summoned

by the king to form a cabinet. Two years later, as head of the

government, he

declared: “We wish to unify the nation within the sovereign State,

which is

above everyone and can afford to be against everyone, since it

represents the

moral continuity of the nation in history. Without the State there is

no

nation.”[26] He was no lover of the state in his days of

journalism, but now he was the state.

So in his speech at the Scala in Milan he coined the formula,

“Everything in

the State, nothing against the State, nothing outside the State.”

Through Sorel’s myth

of action,

Pareto’s concept of the elite, Renan’s definition of a nation, in which

he

recognized pre-Fascist institutions, and a particular interpretation of

Hegel’s

idea of the state, which Giovanni Gentile, the Italian Hegelian

philosopher,

provided for him, Mussolini injected the Fascist myth with vital force.[27] Each of the original ideas was altered to

fit the myth-building mold. Standing between beliefs and ideologies,

the myth

drew from both and rejected both. For example, on religion, he said:

“All

creators of the spirit—starting with those religious—are coming to the

fore, and

nobody dares keep up the attitude of anticlericalism which, for several

decades, was a favorite with Democracy in the Western world. By saying

that God

is returning, we mean that spiritual values are returning.”[28]

But he also said:

Revealed

truths we have torn to shreds, dogmas we have spat upon, we have

rejected all

theories of paradise, we have baffled charlatans—white, red, black

charlatans

who placed miraculous drugs on the market to give ‘happiness’ to

mankind. We do

not believe in programmes, in plans, in saints or apostles, above all

use

believe not in happiness, in salvation, in the promised land.[29]

And then again:

The

Fascist State is not indifferent to religious phenomena in general nor

does it

maintain an attitude of indifference to Roman Catholicism, the special,

positive religion of Italians. The State has not got a theology but it

has a

moral code. The Fascist State sees in religion one of the deepest of

spiritual

manifestations and for this reason it not only respects religion but

defends and

protects it.[30]

Authors who have

covered the

Fascist period in Italy have demonstrated, sometimes abundantly, the

discrepancies between Mussolini’s statements and his versatile policies

in many

domains.[31] There existed, however, a constant in the

evolution of Fascism in Italy: Mussolini’s myth of action and

violence-the

latter as a need for the former. This myth of action had its source in

a number

of factors. There was, of course, Mussolini’s will to power, into which

Pareto’s concept of elites and Sorel’s myth of action and violence,

with some

transformations, fitted well. But there were also the historical,

social and

environmental conditions of Italy. Over half a century before

Mussolini’s march

on Rome, Cavour had said, “We have made Italy, now we have to make

Italians.”

The operation was still in process. The immediate past history of Italy

contained the memories of risorgimento

and the imposing, sometimes dictatorial images of Mazzini and Garibaldi.[32] Mussolini set himself to finish the

operation that Cavour had started by taking inspiration from some of

the

methods used by Mazzini and Garibaldi. For him, to make Italians

progress in

unison, the country had to be on the move. The direction did not

matter. It

would be dictated by the circumstances. Action would bring clashes and

violence, which Mussolini indeed welcomed. He had said in 1920:

Struggle

is at the origin of all things, for life is full of contrasts; there is

love

and hatred, white and black, day and night, good and evil; and until

these contrasts

achieve balance, struggle fatefully remains at the root of human

nature.

However, it is good for it to be so. Today we can indulge in wars,

economic

battles, conflicts of ideas, but if a day came to pass when struggle

ceased to

exist, that day would be tinged with melancholy; it would be a day of

ruin, the

day of ending.[33]

And in his “Dottrina

del fascismo” in 1932, he

reaffirmed that “war alone keys up all human energies to their maximum

tension

and sets a seal of nobility on those peoples who have the courage to

face it.”

Action and violence

through

Mussolini’s will to power within a totalitarian state was the road to

building

Italy as an empire and Italians into a nation. This was a myth of power

rather

than an ideal. To complete Pareto’s definition of the myth as the

deformation

and distortion of philosophical and historical facts, besides toying

with

philosophic ideas in support of the myth, Fascism proceeded to

reinterpret

Roman and world history and to revive imperial folklore and rituals.

Rocco, the

nationalist theoretician who became minister of justice in 1925, called

for a

full-fledged reassessment of history and a reinterpretation of

philosophic and

political thoughts of eminent Italians in order to align them to the

Fascist

doctrine and to show the genius of the Latin mind.[34] Under the direction of De Vecchi a program

to control and revise historical textbooks was undertaken to bring the

facts of

history into line with the Fascist myths. A Fascist academy was created

to

purify the language of foreign influence and to preserve the national

character

and the genius of Italian tradition and culture. Rites and ceremonies

of the

old Roman Empire were imitated. A vast archeological program to dig out

the

vestiges of the Roman Empire was started—notably in the Forum

Romanum—sometimes

at the expense of medieval historical monuments. So Il Duce

could exclaim, “We have created the United State of

Italy-remember that since the Empire Italy had not been a united State!”[35]

and, on the fall of Addis Ababa in 1936 call upon the Italians to

“greet after

an absence of fifteen centuries the appearance of the Empire over the

fateful

hills of Rome.”[36]

National

Socialism

But compared to the

myth that

grew in Germany, Mussolini’s distortions of philosophical and

historical facts

were rather mild. For Hitler had a more potent myth in a more potent

environment. In discussing Hitler’s National Socialism we should make

the

distinction between the distortions of facts in which Hitler “believed”

and the

distortions he “made believe.” His racial prejudices and nationalistic

feelings, were surely deep-rooted. He remained true to his hatred for

the Jews

to the catastrophic end. To some extent because of Marx’s Jewish

ancestry,

Hitler’s early negative trade union experiences and the Jewish

background of

many Social Democrat and Communist leaders, his hate for Social

Democrats and

Communists coincided with his anti-Semitism.[37] He also

connected the Jews to the

international finance and speculative stock exchange operation as

another

source of German misery. The indiscriminate mixture of Jews, Marxists,

Social

Democrats and international finance was a hodgepodge which he labeled

“the

international Marxist Jewish stock exchange parties.”[38] This, however, was a conscious lump-summing

of the target for myth-building purposes:

...It

belongs to the genius of a great leader to make even adversaries far

removed

from one another seem to belong to a single category, because in weak

and

uncertain characters the knowledge of having different enemies can only

too

readily lead to the beginning of doubt in their own right.

Once

the wavering mass sees itself in a struggle against too many enemies,

objectivity will put in an appearance, throwing open the question

whether all

others are really wrong and only their own people or their own movement

are in

the right.[39]

But part of Hitler’s

distortions was in his misconception of historical and economic facts.

Relating

the impact he received from Gottfried Feder’s lectures on economy,

which he had

attended in 1919,[40]

he says:

I began

to study again, and now for the first time really achieved an

understanding of

the content of the Jew Karl Marx’s life effort. Only now did his Kapital

become really intelligible to me, and also

the struggle of the Social Democracy against the national economy,

which aims

only to prepare the ground for the domination of truly international

finance

and stock exchange capital.[41]

He saw as victims to

these

plagues the Aryan people of Germany, who deserved a better lot because:

All the

human culture, all the results of art, science and technology that we

see

before us today, are almost exclusively the creative product of the

Aryan. This

very fact admits of the not unfounded inference that he alone was the

founder

of all higher humanity, therefore representing the prototype of all

that we

understand by the word ‘man’.[42]

This concept of man

obviously

denies a great many historical facts, yet it did work towards molding

the

awesome Third Reich. Its focal point was Volkstum—that is,

“peopleness,” if one

may say so. Volkstum was more than a simple concept of the folk or a

structured

concept of a nation-state. It was the convergence of race, language,

culture,

nation and state, thus going beyond nationhood, providing for the

extreme of

militant nationalism. Its precept was the purification of the Aryan

race,

returning it to its original qualities as the Teutonic, heroic

super-race of

the world—a goal which all ideas, doctrines and knowledge were to serve.[43] Hitler knew, however, that the raw

material—the people—he was to work with was not the finished product he

dreamed

about. From experience, he had learned about the shortcomings of the

people. In

observing the tactics of Social Democrats and trade unions in pre-World

War I

Vienna, he had noticed that:

The

psyche of the great masses is not receptive to anything that is

halfhearted and

weak.

Like

the woman, whose psychic state is determined less by grounds of

abstract reason

than by an indefinable emotional longing for a force which will

complement her

nature, and who, consequently, would rather bow to a strong man than

dominate a

weakling, likewise the masses love a commander more than a petitioner

and feel

inwardly more satisfied by a doctrine, tolerating no other beside

itself, than by

the granting of liberalistic freedom with which, as a rule, they can do

little, and are prone to feel that they have been abandoned. They are

equally unaware

of their shameless spiritual terrorization and the hideous abuse of

their human

freedom, for they absolutely fail to suspect the inner insanity of the

whole

doctrine. All they see is the ruthless force and brutality of its

calculated

manifestations, to which they always submit in the end.[44]

Analyzing the Allied

World War

I propaganda, he had concluded that:

The

receptivity of the great masses is very limited, their intelligence is

small,

but their power of forgetting is enormous. In consequence of these

facts, all

effective propaganda must be limited to a very few points and must harp

on

these in slogans until the last member of the public understands what

you want

him to understand by your slogan.[45]

To this he added that

the task

of propaganda was “not to make an objective study of the truth.”[46] Pondering the Kaiser’s leniency towards

Social Democracy in 1914, he had also noted that the treacherous

opponents of a

regime should be ruthlessly exterminated.[47] Although

there are conditions to be met in

the use of brutal force:

Only in

the steady and constant application of force lies the very first

prerequisite

for success. This persistence, however, can always and only arise from

a

definite spiritual conviction. Any violence which does not spring from

a firm,

spiritual base, will be wavering and uncertain. It lacks the stability

which

can only rest in a fanatical outlook.[48]

Armed with this

knowledge he

had drawn up a 25-point program as early as 1919, which was approved by

the

mass meeting of the National Socialist German Workers Party in February

1920.

It reflected in essence Hitler’s myths, convictions and prejudices—his Weltanschauung. It demanded the union of

all German people in a Great Germany. It emphasized one’s recognition

as German

through .German blood and denied German nationality to the Jews. It

declared

war on the parliamentary system. It also contained Hitler’s ideas to

cultivate

and train the German people’s physical and spiritual gifts through

social and

educational programs carried out by the state. The program’s economic

aspects

reflected Feder’s influence on Hitler and the latter’s lack of

knowledge and

interest in that domain. In a powerful slogan it suggested the breaking

of

interest slavery, the collection of all war profits, and

nationalization of

trusts. This measure, however, was directed against the speculative

stock

exchange capital and not against privately owned industries. Hitler was

in

favor of private capital but wanted to purify it from speculation and

hence

“nationalize” it, i.e., leave it in the hands of German nationals.[49] Economics for him was a means to an end. His

social programs were not socialist in the economic sense, but were

means to

attract mass support before the Nazi seizure of power and to mobilize

the

country for war after he took hold of the government. It was therefore

quite

within Hitler’s rationale later to draw closer to the industrialists

who ended

up supporting his movement and had started their program for rearmament

long

before the Fuhrer came to power.[50] The

National Socialist program was not a

functional plan for social reconstruction. It had as its goal the

purification

and enthronement of the Germanic people as the master race. In keeping

with

Hitler’s observation of the small intelligence and short memory of the

masses,

the myth was to be inculcated into the people by persistent and simple

propaganda,

creating the fanaticism which was needed for the brutal extermination

of all

obstacles on the road to the final goal. While the myth was being

nurtured, the

achievement of its goals had to wait for more appropriate

circumstances, which

did not fail to arise with the great depression of 1929 and the

consequent

economic crises. In the chaos which engulfed Germany the National

Socialist

party, with its uniformed SA (Sturmabteilung:

storm troop) marching to martial music under floating banners and its

fine-tuned

propaganda claiming the ability to provide bread and honor, became a

tantalizing solution. In the September 14, 1930, elections to the

Reichstag,

the number of National Socialist seats jumped from 12 to 107.[51]

It was unfortunate

that Hitler

was so right about so many traits of Parliamentarians, the bourgeoisie

and the

masses. After the arm-twisting of 1932 for wrestling power from

Hindenburg, and

the appointment of Hitler as Chancellor in January, 1933, the National

Socialists organized new elections in a mixture of police state and

revolutionary atmosphere of myth and brutality, securing control of the

government. By a masterful staging of the “day of Potsdam” on March 21,

1933,

commemorating the first Reichstag under Bismarck, Hitler played on the

German

myth to appease the conservatives and the bourgeoisie, thus preparing

favorable

grounds for obtaining the “Enabling Act” two days later, which gave

Hitler the carte blanche to bring about the Third

Reich.[52] Hitler and National Socialism were much more

totalitarian and ruthless than Italian Fascism. In Germany there were

no

dissenters like Gaetano Salvemini or Benedetto Croce who, years after

Mussolini

took power, could still raise their voices in Italy. Hitler eliminated

not only

his active opponents, but even those who had withdrawn from the

political

arena.

In some sectors

slowly, in

others more rapidly, but everywhere surely, all the machinery of the

state was

geared to the service of the Aryan myth. Among other things,

immediately in March 1933, Hitler created a

new

Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda under Joseph Goebbels

which,

within a few months, controlled all mass media. Nazification was

equally

drastic and quick in revamping the educational system from kindergarten

to universities.

The latter lost their autonomy to the Ministry of Education and

introduced

courses on race science and National Socialist philosophy. Parallel to

educational establishments were the “Hitler Youth” and the National

Socialist

Students Federation, which indoctrinated the new generation into Nazi

thought

and used them in turn to indoctrinate and check on their families.

As for the racial

purification

program, the first steps were taken as early as April 1933, when Reich

Minister

Goebbels declared that German Jewry will be annihilated.[53] A law of April 7, 1933, provided for the

pensioning off of civil servants of non-Aryan descent. Another law,

passed on

July 14, 1933, concerned the revocation of naturalization and the

annulment of

German nationality. Still another law for the protection of German

blood and

German honor provided sanction against sexual intercourse between

persons of

mixed blood. These and similar laws aiming at the purification of the

Aryan

race were at times rigorously applied and at other times relaxed for

economic

or political reasons. But by 1939 their overall application had made

the

situation of the Jews in Germany worse than what they had suffered in

the

middle ages when they were at least allowed to participate in economic

and

intellectual activities. As Nolte rightly points out, at that stage the

extermination of the Jews was a matter of course.

The Protestant

churches,

misinterpreting Article 24 of Hitler’s 25-point program, were also off

guard

too long. Although that article did say that the National Socialist

party

“promoted the freedom of all religious confessions within the State,”

it added,

“in so far as they do not endanger the existence of the State or offend

the

ethical and moral feelings of the German race.” It was then in line

with the

ethical and moral feelings of the German race to declare that Jesus

Christ was

Nordic and that the New Testament had been falsified by “rabbi St.

Paul.”

However, the German Christian Faith Movement which was supported by the

Nazis

and proclaimed these theses did not succeed in taking hold of the

Protestant

churches altogether, and finally Hitler had to isolate the Protestant

churches

and combat them from the outside. The Catholics had the political

instrument of

the Center Party which had come into existence to fight Bismarck’s Kulturkampf in the nineteenth century

and resisted Hitler until his accession to power.[54] But after Hitler became head of government,

the Catholic Center Party was dissolved. The Catholic faith and the

activities of

its church in Germany were protected by a Concordat signed in 1933

between the

National Socialist government and the Vatican. There again, Hitler’s

intentions

were misinterpreted. For him, an international agreement was worthy

only in so

far as it helped him towards the final goal of his myth of Aryan

supremacy. In

1933, he created a Reich Church Ministry to supervise the activities of

the

churches. In 1934, Hitler appointed his Nazi philosopher Alfred

Rosenberg as

his plenipotentiary to bring about the total spiritual and

philosophical

education of National Socialism. From then on the part y and the Nazi

government officially promoted the Germanic pagan traditions.[55] Hitler, however, had no intention of

replacing the Christian faith with pagan rites in the supernatural

sense. While

he could not help believing in some supernatural providence as the

promoter of

his destiny, he believed that, in the age of science, knowledge of the

awesome

universe would give man a sense of religion without need for churches,

priests

or even a religious character for his own movement.[56] It is, however, also true that it takes time

to make a religion out of a myth—provided it has the right ingredients.

In

order to make a myth socially functional one has to keep the masses

intoxicated

by the myth and moving to it. Otherwise, its distortions of historical

and

philosophical facts fall apart. The whole of the Nazi programs and

propaganda

served that end. As Fest puts it, it was irrelevant whether Nazism had

a strong

ideology or not; within its grandiose orchestrations, fanfare and

impressive

monumental displays it provided “collective warmth: crowds, heated

faces,

shouts of approval, marches, arms raised in salute.”[57] Leni Riefenstahl’s film, Triumph

of the Will covering the Nazis’ Sixth

Party Congress in Nuremberg in 1934, remains a testimonial document.[58] What was appalling in all this, what made it

a fantastic case of crystallization of values through myth, was the

magnitude

of its process, of how, under favorable social, economic, and political

circumstances, lingering ethnocentric German values and prejudices

distilled

within one man could grow into a thunderous catastrophe.

Hitler discovered

himself an

orator and an actor, but as time went by and success followed success,

he became

more and more convinced of his providential mission and the

righteousness of

his myth.[59] This conviction eventually narrowed his

vision of realities and made him believe in the infallibility of his

fate. As

Bullock puts it:

..the

baffling problem about this strange figure is to determine the degree

to which

he was swept along by a genuine belief in his own inspiration and the

degree to

which he deliberately exploited the irrational side of human nature,

both in

himself and others, with a shrewd calculation. For it is salutary to

recall,

before accepting the Hitler Myth at anything like its face value, that

it was

Hitler who invented the myth, assiduously cultivating and manipulating

it for

his own ends. So long as he did this he was brilliantly successful; it

was when

he began to believe in his own magic, and accept the myth of himself as

true,

that his flair faltered.[60]

For twelve years

Hitler made

Germany the reality of German mythology from Rheingold to

Gotterdammerung. He

played Siegfried and Wotan at the same time, but he finally turned out

Brecht’s

Arturo Ui.[61]

Hitler and Mussolini

acutely

demonstrated the fertilizing properties of myths for state and nation.

In more

or less attenuated doses, myths have always been basic ingredients for

states

and nations. The concept of the greatness of the empire was much older

than

Mussolini, and Hitler did not invent the myth of Aryan superiority.

Writers

like Arthur de Gobineau had developed such theories long before to

explain the

miracles of European expansion and civilization.[62] Indeed, ethnocentric myths conducive to

nationalist feelings are widespread even among peoples whose political

culture

may not show such tendencies. “La culture

civilisatrice francaise” is a historical reality for the French and

was used

to justify a policy of grandeur. “The white man’s burden,” “Rule,

Britannia,

rule,” “Manifest destiny” and “the American dream” are all

myth-building

premises.[63] Nor is the phenomenon exclusive to the

Western world. The Chinese developed the concept of the “Middle

Kingdom” long

before Western ethnocentrism.

III.

Ideology

Besides using man’s

fear and

search of the unknown to form religious and superstitious beliefs or

intoxicating him by energized and deformed facts turned into myths,

values may

be crystallized through man’s capacity to think and to rationalize. The

Cartesian rationale, logical positivism, objective relativism and

dialectical

materialism can equally generate a sense of values.[64]

Of course, the more beliefs are anchored in the beyond, the more

absolute they

will tend to be: the anthropomorphic and metaphysical structures of

belief are

so constructed as to lie outside the confines of reason. Values based

on

rational logic should hold together within the thinking process. In the

latter

case the conditioning of the thinking

process becomes more directly the modus

operandi of the value system. The early Mohammedan soldiers who

fanatically

charged the materially superior Roman and Persian armies believed that

dying

for their faith would bring them to heaven. The militant

revolutionaries who

die under the torture of Gestapo-like police forces also believe—not in

heaven,

but in the righteousness of their cause and its final triumph. The

cause which,

without promising heaven, may claim the ultimate sacrifice is based on

a

rationally concluded and structured system of values.

In 1795, Destutt de

Tracy

coined a term which later evolved to cover this kind of a value

constellation.

He used his term—“ideology”—to refer to a systematic

and rationally concluded body of ideas organized on the basis of

scientific

application of knowledge and experience—hence the “science of ideas.”[65] Marx used “ideology” to refer to the complex

of legal, political, religious, aesthetic and philosophic dimensions,

which

reflected the social conditions, upheld a given social class

structure—notably

the bourgeoisie-and conditioned men’s thinking process or, in his

words, their

consciousness.[66]

The

semantics of the term, however, have evolved since Marx to include his

own

philosophy. Lenin wrote: “Marx was the genius who continued and

completed the

three main ideological currents of the nineteenth century, belonging to

the

three most advanced countries of mankind: classical German philosophy,

classical English political economy, and French Socialism together with

French

revolutionary doctrines in general.”[67] And

according to Althusser: “...in the

present state of Marxist theory strictly conceived, it is not

conceivable that

communism, a new mode of production implying determinate forces of

production

and relations of production, could do without a social organization of

production, and corresponding ideological forms.”[68]

Today the term

generally covers

both the systematic and the systemic

dimensions, and depending on

who is using it where and when, can have different emphasis.[69] In its systemic

connotation, referring to the factors that condition a society into its

particular shape, ideology can be used to encompass the whole of

value-crystallizing processes. When Althusser says that “Human

societies

secrete ideology as the very element and atmosphere indispensable to

their

historical respiration and life,”[70]

he is covering the entire value-crystallizing spectrum. And Santiago

Carrillo

makes the point by identifying the church as an ideological machinery

of the

capitalist state in Spain.[71] While the term is closely related to Marxist

philosophy, its systemic use is widespread. McClosky discerns a

tendency among

contemporary writers to regard ideologies as systems of belief “that

are elaborate,

integrated, and coherent, that justify the exercise of power, explain

and judge

historical events, identify political right and wrong, set forth the

interconnections (causal and moral) between politics and other spheres

of

activity, and furnish guides for action.”[72]

Referring to the

systemic

nature of ideology Marx says:

In the

social production which men carry on they enter into definite relations

that

are indispensable and independent of their will; these relations of

production

correspond to a definite stage of development of their material forces

of

production. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes

the

economic structure of society—the real foundation, on which rises a

legal and

political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of

social

consciousness. The mode of production in material life determines the

social,

political, and intellectual life process in general. It is not the

consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary,

their

social being that determines their consciousness.[73]

According to Marx,

ideology’s

power to condition consciousness is at its peak when it corresponds to

the

relations of production among the different classes of society.

Relations of

production are themselves conditioned by the combination of economic,

technical

and scientific bases—the means and forces-of production. When these

change,

there will be need for change in relations of production among the

social

classes, and this change will sooner or later weaken the prevailing

ideology

and make way for a new one.

When effective,

ideology gives

texture to the prevailing system and justifies its values—its sense of

good and

bad and its moral and social codes. It provides for the society a sense

of

identity which upholds it, warding off alien incursions dangerous to

its

existence. Thus, for example, capitalism, which may have been a

functional

economic process of production and distribution pragmatically based on

the

mechanisms of competitive enterprise and the laws of supply and demand,

becomes

a value-laden system—an ideology—in opposition to another value-laden

economic

concept such as communism.[74]

Capitalism and

communism have

become not merely economic methods for production and distribution of

man’s

material needs but value systems providing pattern and direction for

his

psychological and sociological drives. Affectionally upheld, they are

no longer

functionally analyzable. The capitalist or the communist cannot coldly

scrutinize his ideology and, concluding that it is not workable,

discard it. If

he did, he would lose his identity. The proposition applies not only to

those

of each group who have privileges and reap the fruits of their

ideology, such

as the industrial tycoon in the West or the party official in the East.

The

average man in the capitalist regime would not welcome a system that

denied him

the hope that he may one day become rich under competitive free

enterprise,

which he has come to conceive as the ideal of freedom; and the average

Soviet

citizen is apprehensive about a system which does not provide a planned

economy

wherein he is fitted. An ideology works when it is embraced by the

masses and

prevails as the value-crystallizing channel for the society.

So far, our discussion

of

ideology has not sharply distinguished it from other

value-crystallization

processes. We need to examine more closely the relationship between the

systemic and the systematic characteristics of ideology to identify its

proper

domain and its areas of overlap with beliefs and myths. At the

systematic

level, we said, ideology draws its arguments from rational and

scientific

premises. That requires, of course, consciousness of all the aspects of

the

subject under consideration, including their contradictions;

objectivity and

abstention from dogmatism in theory; rigor and presentation of

conclusions by

verifiable facts in practice. To gain insight as to how scientific

consciousness leads to conditioned consciousness, we can start by

looking into

the components of the systematic dimension of ideology.

To arrive at his

statement

quoted earlier about the conditioned consciousness of the masses, Marx

had to

make a conscious effort to observe social phenomena. This fact that he

could

surmount his own conditioned consciousness in itself contradicted his

statement

and permitted him to discover the inherent contradictions within the

social

structure. In other words, his scientific method was dialectical.

Dialectics

was not new. Ever since Zeno, it had connoted a method of study,

recognizing the

interrelatedness of phenomena, their flux and their inherent

contradictions.[75] More recently, Hegel—in his method, but not

in his conclusions—had followed this pattern to which he had added, in

his

treatment of measure, the relationship of quantity and quality.[76] But Hegelian dialectics had strong

metaphysical flavor. Hegel elaborated historical dialectics as a theory

of

logic to demonstrate rationally the relationship between reality and

values. He

postulated that this relationship could be grasped through an

understanding of

the relationship between the ideas of phenomena and the phenomena

themselves

and their evolution. This would ultimately demonstrate, through the

reasoning

process, the relationship of reason to Absolute Reason.

While using the

Hegelian

dialectical method for historical analysis, Marx and Engels replaced

his

idealism, which to them was the mystification of the real, with

materialism. In

that sense the Marxian dialectic method was the inversion of the

Hegelian.[77]

It was not by logically analyzing the idea of things that one could

understand

reality and its relation to value, Marx said, but by examining the

reality

itself.[78]

Reality is material, i.e., made of matter. Consequently, materialism

maintains

that matter is primary and thought and idea are secondary.[79] That is, thought is a product of the brain,

which is made of matter:[80] “Mind itself is merely the highest product

of matter.”[81] Since nature’s process is dialectical and

not metaphysical,[82]

and since

mind is the highest material product, “dialectical materialism ‘no

longer needs

any philosophy standing above the other sciences,”’[83]

for “there are no things in the world which are unknowable, but only

things

which are still not known, but which will be disclosed and made known

by the efforts

of science and practice.”[84]

Science and practice,

however,

cannot be uttered in the same breath without qualifications, especially

in

relation to social and political phenomena. Scientific inquiry—search

for and

grasp of abstract knowledge, theorizing-often calls for a different

kind of

temperament than does practical endeavor. Some feel more comfortable

having a

conditioned consciousness with established goals and values rather than

having

a conscious mind groping with dialectics of contradictions. This is a

social

reality which some consider changeable; i.e., they believe it is

possible to

make every member of society enjoy dialectical consciousness. Without

getting

involved in biological, ethological or psychological debate on this

issue, we

may reasonably assume that to achieve that goal scientific knowledge

should be

applied in practice. That is where, in general socio-political terms,

difficulties arise, because scientific knowledge is not always socially

operational.

We can, of course,

start at the

stage where scientific knowledge and conscious minds are the attributes

of a

certain segment of the society whose vested interest is to keep things

as they

are. That is, the masses have imbibed the ideology at its systemic

level while

the privileged class may be conscious of its contradictions at the

systematic

level but keeps mystifying the masses. The taxi driver lauds the

capitalist

system because he is his own boss, yet tie works twelve hours a day six

days a

week to pay the bank, the insurance company and taxes which go for

government

contracts and appeasement of the downtrodden through handouts. However,

as we

said earlier, classes are not tightly confined compartments. When

changes in

the relationship of production become more and more flagrant, in the

course of

repeated practice, as Mao Tse-Tung puts it, a change takes place in the

brain

in the process of cognition, and concepts are formed.[85] Within the masses a consciousness of

contradictions can begin to grow. This consciousness, however, may not

be

“scientific” in analyzing the overall contradictions but systemic in

that it

may lead to the knowledge of manipulating the rules within the system.

Lenin

was concerned about this:

We have

said that there could not yet be

Social-Democratic consciousness among the workers. It could only be

brought to

them from without. The history of all countries shows that the working

class,

exclusively by its own effort, is able to develop only trade union

consciousness, i.e., the conviction that. it is necessary to combine in

unions,

fight the employers and strive to compel the government to pass

necessary labor

legislation ....

Social-Democracy

leads the struggle of the working class not only for better terms for

the sale

of labour power, but also for the abolition of the social system which

compels

the propertyless to sell themselves to the rich. Social-Democracy

represents

the working class not in the latter’s relation to only a given group o

f

employers, but in its relation to all classes of modern society, to the

state

as an organized political force ....

Working-class

consciousness cannot be genuinely political consciousness unless the

workers

are trained to respond to all cases, without exception, of tyranny,

oppression,

violence and abuse, no matter what class is affected. Moreover, to

respond from

a Social-Democratic, and not from any other point of view.[86]

Scientific theory can

thus

supersede what in narrow practice may seem an appropriate course of

action. But

at this stage too, looking closer, we find the conscious mind of the

Communist

(Social-Democratic) Party leading the conditioned consciousness of the

proletariat. In terms of dialectics, of course, this amounts to party

control

in the systemic sense of ideology. Evidence to this effect are

developments in

the Soviet Union and other socialist states on which we are now getting

first-hand critical analysis.[87] The process corresponds to the general

concepts relating to group dynamics and the need for a value system

discussed

earlier. Sartre points out: “As an institution, a party has an

institutionalized mode of thought—meaning something which deviates from

reality—and comes essentially to reflect

no more than its own organization, in effect ideological thought.”[88]

Thus, as the party gains control, rational knowledge is conditioned by

the

ultimate goals and practices of the party and of the state controlled

by it. In

the name of the systematics of ideology a party may modify its guiding

principles and reject dogmatism which could encumber it and threaten

its continuity

(such as the Marxian proposition that the state will wither away). And

in order

to perpetuate the systemics of ideology keeping it in control, it may

reject

scientific empiricism which, if practiced widely among the masses,

would void

the value connotations of its theories and leave no ladder by which the

party

could claim ascendance over individual consciousness. In his analysis

of Soviet

Marxism, Marcuse elaborates on the magical and ritualized character of

the

official language in the Soviet Union and the rigidly canonized

statements by

the Soviets on their society “which are obviously false—both by Marxian

and

non-Marxian criteria,” but which in the context of Soviet political

practice

are aimed at historical processes, which will bring about

the desired facts.[89] This is ideology in the systemic sense,

fading into myth-building. When a scientific theory such as Marxism is

fixed as

a goal—as it is in the Soviet Union—and when in its name dialectical

contradictions to state practice are suppressed, the dialectical

flexibility of

the complex for synthesis is reduced, opening the door to deviations

from the

original theory. The systematic is turned into systemics of

ideology—rational

thinking into rationalization. Ideology, having thus become the

instrument to

perpetuate a given social structure and social stratum (the party),

will, in

the purest Marxian dialectics, nurture within its womb a new current,

represented in the Soviet Union by a line of dissidents such as

Pasternak,

Daniel, Sinyavsky, Solzhenitsyn, Amalrik, Sakharov, or Shcharansky,

whose

consciousness of contradictions underscores the conditioning of

consciousness

of the masses.

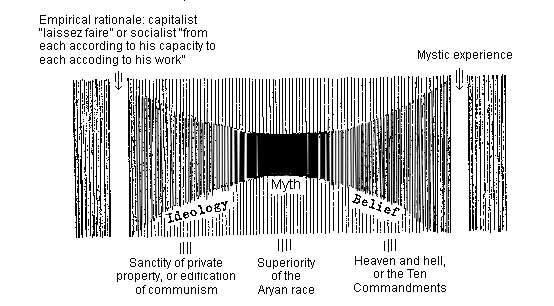

IV. The

Belief-Myth-Ideology Spectrum

At the beginning of

this

chapter we set out to unravel some of the particularities of the major

social

processes of value-crystallization. This we did despite the fact—as we

pointed

out—that often one of the terms is broadly applied for the whole

spectrum of

value systems. We hope that while showing the particular

characteristics of

beliefs, myths and ideologies, we have also provided enough clues to

demonstrate why the terms are interchanged. In discussing each process,

we

distinguished it from the others mainly at its essential origin, or

original

essence. We saw that the supernatural, religious and metaphysical

premises of a

belief are generally based on mystic experience, but also that at its

pure

stage, the mystic experience is personal and not transferable.

Bodhidharma

said,

Enlightenment

is naught to be obtained,

And he

that gains it does not say he knows.

A mystic experience,

to be made

socially operational in support of a value system, must be adapted and

transformed. You will notice how great are the chances that an

experience which

is not transferable in the first place can be distorted as it is

adapted and

transformed. The more the mystic origin of a belief is voluntarily

distorted

for social action and organization, the more it falls into the realm of

myths

which, as we saw, were brought about by conscious and systematic

distortion of

historical and philosophical facts.

Similarly, purely

scientific

conclusions based on rational and dialectic observations and research,

as we

saw, are not in essence supposed to have any value charge. In the words

of

Mannheim:

The

term

‘ideology’ in the sociology of knowledge has no moral or denunciatory

intent.

It points rather to a research interest which leads to the raising of

the

question when and where social structures come to express themselves in

the

structure of assertions, and in what sense the former concretely

determine the

latter.[90]

Adam Smith did not

establish

sanctity for private enterprise, rent, interest and commercial profit.

Indeed,

he pointed out that “in this [original] state of things, the whole

produce of

labor belongs to the laborer,” but that the incentive which private

ownership

of capital and commercial gain provides for the accumulation of wealth,

needed

for economic development, justifies capitalism and free enterprise.[91] Nor do the historical fact of class

antagonisms combined with the rationale of “from each according to his

capacity, to each according to his work,” lead to the conclusion that

each

should or will give according to his capacity and receive according to

his

need. Here again, to bridge the gap, some ideological acrobatics are

needed. To

serve the value-crystallization purposes of a particular social order,

an

ideology has to indulge in half-conscious and unwitting disguises

or-conscious

lies[92]--a

process which will move ideology toward myth.

We thus have a

spectrum with at

one extreme the detached and socially non-operative mystic experience

of the

sage or saint—the pure “value”—and at the other the “value-free”

empirical and

scientific rationale. As their adaptation for purposes of social

organization

is undertaken—on one side through religious beliefs, on the other

through

ideologies—the two are modified, transformed and distorted to provide

value

systems for social order. The more religions and ideologies transform

and

distort their original mystic and rational premises respectively, the

more they

approach the middle of the spectrum, where lie the myths with the

greatest

distortion of historical and philosophical facts.

Fig.

5.01

Our spectrum further

reveals—or

rather reiterates—the two interacting social and individual dimensions

of the

value-crystallization process and the relative doses of each under

different

conditions. Nearer to the individual mystic or rational dimensions,

where the

beliefs and ideological premises of individual group members are more

likely to

emanate from inner convictions, social action for value-crystallization

may be

less apparent for creating predictable and uniform behavior among group

members. Not that social action has not already conditioned and

continues to

reinforce the members to believe or rationalize as they do, but that

the

process and its effects are latent enough to make values sink into each

individual’s complex of action. Where the individual group members,

rather than

believing or rationalizing, should be intoxicated to follow a myth as

the basis

for the value system, social action needs to be dramatized and

engrossed to the

saturation point.

All these

circumstances refer,

of course, to situations where, whether through the individual

convictions of

group members or social action in a monolithic context, a potent value

system

gives the group a particular social texture. But what happens to social

cohesion if a monolithic value pattern cannot be maintained, because

the

heterogeneity of a society provides alternatives, resistance and

contradictions

to the value-crystallization process? Our question leads us into the

thick of

the socio-political complex because, while beliefs, myths and

ideologies are

the sources of social and political organization, they do not often

constitute,

in any pure state, the blueprint for that organization. And if that may

be so,

in order not to take our assumptions as facts, we will need to look

more

closely at the realities of value systems within the social context.

This is one of those

occasions

where the writer wishes he could, like the painter, simultaneously

impress upon

his audience all of the intertwining filaments stretching out of what

has been

developed so far. At this point in our inquiry, to answer the question

we have

posed, we are faced all at once with such problems as: How are the

interaction

and transformation of individual and social dimensions in the

value-crystallization process made possible? (which leads us to a very

basic

inquiry into the communications process and its ingredients—signs,

symbols and

rituals). How are the interaction of individual and social dimensions

in the

context of value systems made socially functional? (which leads us to

social

norms). By what agencies are values and social norms formed in the

social

context? And how do those agencies and the members of the society fit

together

within the social pattern? Alas, we cannot study all of these questions

at

once. But while discussing each, let us keep the others in mind.