Chapter

3

Group

Fermentations

and

Dynamics

He who is unable to

live in society,

or who has no need

because he is

sufficient to himself,

must be either

a beast

or a god.

Aristotle

The raw material

provided in the last chapter can already

serve for building a model to explain some political structures. But at

this

stage the model would be rudimentary and, beyond generalizations of

culture-universal nature, would not explain the political varieties

which

result as different phenomena combine. For example, on one hand,

man's

drive for self-preservation and satisfaction of his physiological needs

and, on

the other, his search for challenge, combined with the domination drive

of some

and the submissiveness of others, may account for political hierarchy.

But with

only our present premises, it would be difficult to explain, for

instance,

political continuity and change, or the reason some human groups seem

to draw

inspiration from Mill for their political organization while others are

more

influenced by Hobbes. In other words, we need additional dimensions

beyond the

basic drives to explain the diversified political

behaviors, processes and institutions and to show reasons for their

differences

and similarities.

Discussing the drives

which qualify man as a political

animal, and looking at the phenomena from the individual's point of

view, we

noticed that the group is our basic term of reference for examining

man. Man's

association with his fellows. to satisfy his physiological,

psychological and

sociological needs can be conceived only within the group. Thus, for

the

additional dimensions we will look more closely at man in his elemental

context, the group.

I.

The Individual and

the Group

Indeed, keeping a

balanced view of the roles of both the

individual and the group is a constant problem in social and behavioral

studies. Through the ages and with quite diversified philosophies,

some,

including Plato, Aristotle, St. Thomas Aquinas, Marsilio of Padua, Sir

Thomas

More, Hobbes, Hegel and Bosanquet, to name a few, have maintained that

man

makes sense only in relation to the group. Others, as diversified as

Diogenes

or Seneca in ancient times and Locke, Kant, Bentham and Mill more

recently,

have seen the individual and his behavior as the gist of human

existence and

social life.

The position of each

of these thinkers and his respective

philosophy should obviously be examined in the context of his time and

environment, as should those of different contemporary schools. Thus,

for

example, while psychologists, such as those of the Gestalt school, have

moved

towards group theory in reaction to the Freudian emphasis on the

individual,

political scientists have tried to avoid the atomist liberalism of the

nineteenth century which emphasized individuals in their singularity in

opposition to the state as a political entity.

Moving also away from the prevailing structured, static and

institutional approach of their discipline, some twentieth-century

political

scientists came to consider the group the main dynamic entity which

both molds

the socialized individuals and structures the institutions.[2] These theoretical approaches fluctuate with

the times.[3] But in general, in a civilization where the

tendency towards specialization in knowledge and uniformity in outlook

seems to

be the trend, where the average individual is average because he is

diluted in

the masses, and where the motor

personality can hardly function individually but needs group

support, it is

only natural that the focus turn to the group.[4]

Yet, while the study

and analysis of groups, their

fermentations and dynamics will answer many questions, it may not

answer all of

them. It would be unrealistic to espouse total group theory for

political

analysis. The group is not an amorphous entity. It is made up of

components

which, in the last analysis, are individuals. In the words of Latham:

Groups

exist for the individuals

to whom they belong; by his membership in them the individual fulfills

personal

values and felt needs ....Recognition of the place and role of the

individual

in group associations avoids the error of supposing that political

processes

move by a blind voluntarism in a Schopenhaueresque world .... the whole

structure of society is associational; neither disjected nor congealed,

it is

not a multiplicity of discontinuous persons, nor yet a solid fusion of

dissolved components.[5]

Going further, we may

see individuals at times playing

roles which surpass group identification and influence the course of

action of

the group or of many groups. Some poets, philosophers, heroes and

leaders have

been lone riders, so to speak, remaining aloof from the group or using

groups

to ascend toward their ideals and goals. Sometimes they have become the

focus

of reference or of crystallization for groups which have gravitated

around them

without integrating them. The motor personality may influence the group

without

necessarily heading a movement. He may lead only in thought, without

the

charismatic and other qualities of a militant leader. Rousseau was

neither a

leader nor a hero, but what he said--in itself not a very practical

theory for

social organization--had great impact on the future course of France.

Marx was

another such motor personality.

Such associations may

occur only in certain periods of

the individual's lifetime and in certain circumstances of group life.

But the

point is that they can occur. Personalities like Caesar, Joan of Arc or

de

Gaulle did not exactly fit any particular group. In examining heroic

leadership, Hoffman says:

The

heroic leader is, with

reference to "routine authority", the outsider in two significant

ways. He tends to be a man who has not played the game, either because

he has

had little contact with the political arena (an indispensable quality

when the

crisis that brings him to power amounts to the collapse, and not merely

the

stalemate of the regular regime) or, if he has been in it, because he

has shown

impatience with the rituals and the rules.[6]

Of course, this kind

of personality does not descend

among the group out of the blue. He himself has obviously been

socialized. But

we mention the impact of such a personality on the group as an extreme

case of

the possible role of the group components. We are distinguishing

between the

individual's socialization and his group identification for social

action. Even

empirical studies and experiments directed at group pressure for

conformity

have had to distinguish between "naive" and "independent"

subjects.[7]

Those within the group

who are more instruments than

instrumental constitute, by conforming and behaving predictably, the

group's

identifiable texture. Some groups provide little possibility or room

for motor

personalities to blossom--such as folk societies, with their strict

structures

and limited environmental potentials, which we shall examine later. We

must

not, however, lose sight of the trees while looking at the forest. At

the

practical level of political science, after the analysis of group

dynamics, we

need to know the role and impact of the individuals making up the

group. Even

in its collectivity, the group, as Latham said, consists of components

which

define its character. The candidate who knows who the influential party

leaders

are, or the employer who knows which union workers to contact, can

better

influence the group with which he deals. And each group and its

components have

particular characteristics. A demagogue can use a mob but may be

considered a

nuisance if he starts haranguing the public at a movie theater. The

successful

political practitioner knows which group to use in what circumstances

and how

to use it. A Lenin or a Hitler can do to a crowd what only a few can.

And not

only do such men create an impact which lasts beyond the life of the

crowd, but

they manage to manipulate the crowd without being carried away by it.

II.

Group Association

The group's nature,

size, context, cohesion, duration and

environmental circumstances all shape its interaction with its

components.[8] At the minimum extreme of some of these

factors, the group may not show much groupness. The wearers of shoe

size 8,

those in the $20,000 annual income bracket, or those 35 years old have common characteristics but are not

always conscious of their groupness. For the political analyst,

however, they

may constitute a categorized group worthy of consideration.[9] Members of a categorized

group may seek each other out when circumstances make

them conscious of their common identity.

Consciousness of

groupness does not necessarily imply

proximity and vice versa. VFW members do not need a convention to react

in a

similar manner to an issue, while a movie audience may include members

of some

categorized groups who may not acknowledge each other. The movie

audience is an

aggregate whose individual components

are at the theater for a purpose independent of their coincidental

togetherness. Physical nearness, however, is the

particular characteristic of the aggregate which is felt by its

individual

components. An extreme illustration of it would be the panic felt if

fire broke

out in the theater. Without going to that extreme, we can say that the

reaction

of the members of the audience to what is being projected on the screen

can be

influenced by the aggregate around them. If the viewer watches the same

program

on TV alone without the surrounding charge

of the crowd, he may receive a different stimulus from the movie. We

distinguish two charges here: that of the group and that of the exposure to a program. The movie

watchers, whether at the theatre or at home, are categorized groups

because of

their exposure to a given program rather than who they are. True,

certain kinds

of people watch certain kinds of movies. But their common

characteristics

develop also because of their previous experiences. Those with higher

education

may watch scientific programs more than others because in college they

were

exposed to science. Beyond long lasting effects, exposure can produce

immediate

group dynamics. The classic case of Orson Welles' radio adaptation of

H. G.

Wells' novel, The War of the Worlds,

on October 30, 1938, over CBS was one occasion when the charge of

exposure was

so great that the radio listeners took to the streets.[10] The exposure to a particular stimulus thus

created a spontaneous group and the

charge of the two triggered a mob.

A mob can carry its

components away. It behaves as an

organism, acting and reacting as such. "It" breaks windows, while

many of its components as individuals, and maybe even the one who

hurled the

stone at the window, would not otherwise throw stones. A mob, while

behaving as

an organism, may not follow a set pattern organically--although it may,

in its

short-term existence, produce detectable patterns.[11] This fact makes a mob, under favorable

circumstances, vulnerable to manipulations which can organize it as a

tool for

a purpose--often political.

Examining the factors

so far elaborated we may find other

variations of group associations. Thus, the more an assembly of

individuals

gathered as a short-term group follows an organized pattern of behavior

for a

purpose, such as a picket of strikers or a demonstration for a

political issue,

the less it can be qualified as a mob. The extreme of such organization

is a

parading army. If the picket or demonstration turns into a mob, it is

that it

had the germs and characteristics of a mob. It must have been

inadequately

organized to cope with all possible circumstances, its declared purpose

must

have been only partially adhered to, and it must have been prone to

manipulation.

A short-term assembly

of individuals organized for a

particular purpose, whether a picket or a demonstration, should, in the

last

analysis, be considered as part and extension of a long-term constituted group which is organic--in

the sense that it is

organized--and not coincidental or spontaneous. The main characteristic

of an

organic group is consciousness of its groupness. An organic group may

be constituted, either through intentional

and voluntary association of

its members as are pressure groups, lobbies or humanitarian

foundations, or it

may be a circumstantial converging

association like a legislative body, where the members do not seek

each

other out but still end up in a constituted group. Further along the

line we

may identify organic groups like folk societies and primeval tribes,

which can

be labeled immanent in that they may

not have come together voluntarily. One is born in one's own family.

Group associations

imply different degrees of involvement

by the members and different attitudes and behaviors on their part

towards the

group and other group members. In sociology a distinction has been made

between

primary groups and secondary groups. The distinction is based on the

nature and

structure of the groups. The members of a primary group are closely

associated

in an intimate, face-to-face and durable environment. Cooley, who

developed the

idea of primary groups, conceived of them in the context of family,

playground

and neighborhood. Secondary groups are defined as larger, more

impersonal

social bodies with which. the individual establishes formal

relationships. Cooley

attributed to the primary group an ideal-molding character which "in

its

most general form... is that of a moral whole or community wherein

individual

minds are merged and the higher capacities of the members find total

and

adequate expression."[12] He recognized, however, that they did not

realize ideal conditions. He deplored .that "in our own life the

intimacy

of the neighborhood has been broken up by the growth of an intricate

mesh of

wider contacts which leaves us strangers to people who live in the same

house."[13] Kingsley Davis, who developed further the

concept of the primary group, also recognized that primary

relationships do not

exist in concrete forms and that in actual groups of a close and

intimate kind,

characteristics contrary to those attributed to primary groups may

exist. He

noted, for example, that:

Neighborhood

and family control

is very complete control, and the individual often wishes to escape it

by

getting into the anonymous and more impersonal life of a larger setting

such as

a big city. The truth is that such actual groups embody only

imperfectly the

primary relationship. They demand a great deal of loyalty and they have

an

element of status, of institutionalization, in them which makes them

something

less than spontaneous and free.[14]

In other words, the

types of relationships attributed to

primary groups are neither confined to, nor necessarily identifiable

with such

groups as family and neighborhood.

Indeed, within the

more impersonal and segmented

structure of what is sociologically termed a secondary

group, i.e., the complex industrial society where people

commit themselves to the larger group along the lines of the division

of labor

for achieving personal and social goals, smaller groups of . a

primary-group

nature may form. The worker in a factory, the secretary in a

bureaucratic

organization, and the salesman in a department store may soon find

themselves

incorporated into a group with the traits of a primary group. Further,

with

their superiors or subordinates they may develop relations beyond the

impersonal segmentation of a secondary group. In such circumstances the

specific characteristics of primary relationships may become relative.

With

greater need for solidarity and mutual affection, the required duration

of

intimate, face-to-face contact to establish primary relations may

become

considerably shorter than in the classic family situation.[15]

The classification of

groups into primary and secondary

leaves us with certain ambiguities. The characteristics attributed to

each category

do not necessarily coincide with it. In the interpersonal relations of

members

of different groups we may find both primary and secondary dimensions.

Yet for

our political analysis we need a clearer idea of the nature of these

relations.

Let us, therefore, devise a model based on the nature of the behavior

of the

group members and their inter-personal relations in different group

contexts,

rather than on the structure and nature of the groups. Obviously, some

behaviors and relations are likely to recur more in certain types of

groups

than in others. But our purpose is to take the nature of behavior and

interpersonal relations of group members as our subject--rather than to

treat

the group as the subject and the pattern of its members' behavior as

the object.

III.

Affectional and Functional Relations

In discussing groups

as primary and secondary, we noticed

that the interpersonal relations and attitudes of group members could

fall into

two general categories. Those relations such as love, sympathy,

empathy,

intimacy, resentment or hate which are based on feelings, sentiments,

emotions

and affections. In a sense, at least materially, they are nonrational.

And

those that are the more impersonal associations, which further specific

goals,

are largely functional in their social context (e.g., negotiating with

a

dealer, or doing a job for pay). From the

point of view of personal and/ or social ends, they have a

rationale. We

may thus conceive of a range of behavior from the emotional to the

rational. Of

course, for our political analysis we may draw more heavily on certain

sectors

of this spectrum.

Affectional

Relations

As we pointed out in

the last chapter, man's association

with his fellow men to satisfy his basic needs develops according to

physiological, psychological, and sociological dimensions which

interact in

varying degrees. Not only does man have natural tendencies to search

for

contact-comfort and to be gregarious, but one of his physiological

needs,

namely sex, calls for companionship. Mating, combined with the long

weaning and

rearing period of children, can cause group members to develop

relations which

cannot be directly explained by the rationales of material

satisfaction. One

may alienate or even kill one's mate in jealousy or parents may risk

their

lives to save their child. These we may call affectional

relations. By this term we imply a continuous pattern.

In other words, for our socio-political analysis we need not be

concerned with

sporadic "emotions." They belong more to psychological studies-that

is, emotional relations in their microcosmic dimension. For example,

one may

feel anger, disgust or even hatred toward his friend or parents in a

particular

situation, or may momentarily admire his enemy. As long as these

emotions

remain isolated, they may not change the general, long-term positive or

negative pattern of affectional relations. Short-term fluctuations of

emotions

and sentiments indeed influence and shape affectional relations, but

their

spontaneity and evanescence do not always reflect social phenomena; if they do, they become our concern.

As our examples imply,

affectional relations are not

meant only to connote positive affections but to cover all human

social-attitudinal dimensions not directly materially oriented, whether

positive

or negative. It is their omnipresent, nonrational intensity that

identifies

them as affectional. As we saw in the last chapter, both attachments

and

interpersonal tensions are stronger within the closer circle of

relations

because of the conflicting tendencies: 1) to draw one's satisfactions

from

those closely related, and 2) to want freedom from their confinement.

Functional

Relations

Relations within the

group for the satisfaction of

material needs can be identified as functional

relations. These, in our terminology, are social relations which,

while

more impersonal and businesslike, coexist with affectional relations

and, in

the last analysis, serve as a breeding ground for them. The term is

intended to

connote a set of arrangements which, although impersonal, are

interpersonal and

transactional. In their social context they do not go as far as the

extreme of

the individual's purely selfish state-of-nature

rationale for the direct satisfaction

of his material needs, nor do they reach the ideal

mechanical rationale for a "perfect social order"

which could abstract human nature and feelings. By way of illustration,

at the

extreme of state-of-nature rationale,

we may say that it would be rational on the part of a hungry individual

to grab

the bread displayed in the bakery and eat it without paying for it. But

if this

act, without being the norm, were repeated, we would revert to the

state of

nature where there would be no bread, no baker and no group. Or at the

extreme

of ideal mechanical rationale we may

conceive of a perfect order which could permanently supply vitamins,

proteins

and nutrients into the body, eradicating hunger from man's organism and

rendering him a rational robot without conscious dependence on his

fellow men,

programmed for ideal efficiency in his tasks without discriminatory

feelings.

If drawn to these extremes our term "functional relations," will lose

its reference to material social realities and arrangements in the

context of

present human social potentials. In this social context certain

functions must

be performed before the bread can reach the hungry man's mouth, and the

man

should be hungry in order that certain social functions be fulfilled.

For one

thing, the hungry man has to "pay" for the food, which means that,

like the baker who has baked the bread, he has to contribute his share

of work

to the society, thus fulfilling a function within the group. The Bible

says,

"if any would not work, neither should he eat," and the 1936 Soviet

Constitution said, "He who does not work, neither shall he eat!"[16]

Common

Grounds of Affectional and

Functional Relations

But functional

relations vary under different

circumstances. The baker may give the hungry man free bread because

they are

relatives or friends, or he may do so in the name of humanity. Here,

some

affectional elements influence the functional relations. Inversely, the

baker

may coldly calculate the hungry man's need for bread and make a demand

on him

which does not correspond to the group's standards for a baker, but

which does

contribute, in the baker's rationale, to his material satisfaction. In

this

situation the baker's functional behavior departs from the human

affectional

context and tends towards the state-of-nature

rationale of "every man for himself."

For purposes of

distinction, the terms

"affectional" and "functional" relations are better

identifiable when each approaches its non-social extreme: short-term

emotional

behavior on the affectional side, and either the state-of-nature or the

ideal

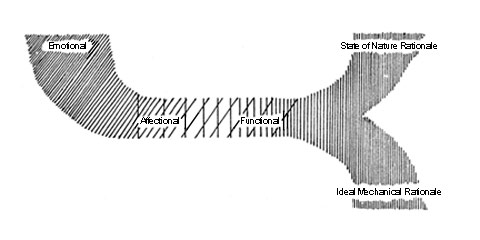

mechanical rationale on the functional side (see Fig. 3.01).

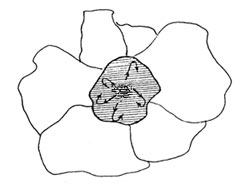

Fig.

3.01

While both the state

of nature rationale of the Hobbesian

pre-Leviathian type and the mechanical ideal rationale of the Huxleyan Brave New World type are placed on the

same side of our spectrum, they are themselves opposites. The first

implies

total lack of integration, the other total integration, denying any

personality

to the individual. On the whole, social life becomes intolerable as we

approach

the extreme of emotional fluctuations or the rationale of the state of

nature

or of mechanically perfect organization.[17] The

interpenetrating affectional and

functional relations in the middle of our spectrum cover the area where

group

life and social organization are possible. The emphasis on the

interpenetration

of the affectional and the functional relations shifts depending on the

particular needs of a given social organization. For example, love is

not

always coupled with parenthood. In 1935 Margaret Mead researched the

Mundugumor

people of New Guinea who displayed no parental love because material

abundance

reduced the need for such affectional relationships supporting

functional

interdependence.[18] On the other side of the same coin, Colin M.

Turnbull reports that the Ik people, deprived of the resources of their

nomadic

life in Uganda, led a near starvation subsistence which reduced their

affectional ties to the point that a mother was relieved if her child

was

carried away by a predator. Since no functional ties could be

developed,

affectional ties diminished.[19] The relationships among members of a nuclear

family--between wife and husband or parents and children--are not only

affectional, based on a community of feelings and sentiments, but also

subject

to social rules, whether traditional or institutional. At any level of

social

evolution--whether among the Trobriand Islanders or in an industrial

society--familial affectional ties are intertwined with such

relationships as

marriage and inheritance, regulated by functional norms. Similarly,

institutional arrangements of a functional nature bear the imprint of

man's

affectional tendencies. Affectional relationships develop among those

functionally in contact and related: the employer and the employee, the

superior and the subordinate, the producer and the consumer.[20]

Of course, with more

contact, affectional relationships

grow. Contact means not only the physical sharing of time and space,

but also

the possibility of communication and sharing of values and standards.

Thus, the

fewer similarities among those functionally in contact, the smaller the

affectional dimension of their relationship, approaching the mechanical

or

state-of-nature rationale. The relationship between officials of the

Egyptian

pharaohs and their slaves, the colonial administrators and the

indigenous

Coolies, the Nazis and their forced laborers were generally at the

functional

extreme, approaching the state-of-nature and mechanical rationales,

with little

room for the laborers' dignity in the masters' material calculations.

Inversely, common values and standards may impregnate functional

relationships

where physical, spatial and temporal contacts are minimal. Thus, at a

given

level of social development, independent of personal contacts, the

employer may

provide sick leave for his employee, whereas from a material rationale

he could

dismiss and replace him. In such a case affectional relations are

injected into

the functional, reflecting standards of social justice. We must hasten

to add,

however, that such cases of uncoerced affectional feelings seldom

arise. They

become generally accepted standards as a result of social conflicts and

struggles, which belong to the functional domain.

Extending our model,

we may also conceive of affectional

relations growing out of other kinds of closeness, such as feelings of

belonging to the same culture, ethnic group, race or religion. Such,

for

example, is the sense of solidarity between the Americans and

Australians based

on their presumed Anglo-Saxon background, as compared to the relations

between

Japan and the U.S.A. which, though more extensive, are at this stage

more

functional. The time factor should, of course, be borne in mind. The

nature of

these relations may well change over a long period of contact.

Similarly, distant

affectional and functional relations

may be more pronounced in different spheres and under different

circumstances.

The relationship of a North Dakota farmer with a Detroit auto worker is

indirectly functional as it concerns their professional roles within

the

American division of labor. But, as American citizens faced with an

international conflict, they may develop indirectly affectional

relations. For

example, without knowing him personally, one of them may learn of the

other as

a prisoner of war and emphathize with him. As our various

illustrations and

examples show, affectional and functional dimensions are present in

interpersonal relations, as well as in the feelings, attitudes and

behavior of

group members towards part of the group or the group as a whole. From

microgroup to macrogroup, we may speak of such affectional relations as

paternal love, friendship, comradeship, esprit

de corps, sympathy and, further, faith, belief and patriotism. The

latter

categories demonstrate the nonrational, affectional ties between group

members and

the group as a whole on the basis of abstract religious, ethnic or

territorial

identifications. We shall discuss these dimensions in more detail

later. On the

functional side, we can also lay out a range of institutions from the

microgroup to the macrogroup, from marriage, heritage, adoption and

other forms

of contracts, to all the social and political institutions, like

business,

industry, bureaucracy, church and state.

A further look at our

examples will reveal how

affectional relations justify functional structures, as love and

companionship

do for the institution of marriage, or faith does for the church.

Inversely,

functionally constituted institutions develop affectional dimensions,

such as

the professional solidarity and comradeship among small groups of

workers in an

industry or among soldiers in an army, or patriotic feelings in a state

as it

grows into nationhood. We may also notice briefly, at this stage, that

the

coexistence of affectional and functional relations and the

possibilities of converting

one into the other are instrumental in the political structure of the

group and

the society. This is the aspect of our model which directly interests

us and

calls for further inquiry into the political texture-of groups of

different

sizes and natures in time and space.

IV.

Size and Nature of Groups

In the.preceding pages

we referred to a variety of groups

within which we could detect different combinations of affectional and

functional relations. These combinations are both cause and effect of

the

group's characteristics. The study of these characteristics can shed

light on

the development and evolution of political behaviors, processes and

institutions permitting us to see whether human groups share common

denominators and general patterns which could be used for our study. Is

there

any similarity of social structure between the present-day tribes of

Australian Aborigines and the inhabitants of Helsinki? If there are

differences, how have they come about? After all, according to the

description Tacitus

gives of the Fenni, the ancestors of the population of Helsinki, their

social

and political system was not much more elaborate than that of the

present

Australian Aborigines; nor for that matter were those of other German

tribes as

compared to contemporary primeval tribes.[21] Indeed,

many parallels can be drawn between

the mores, rituals, laws, beliefs, traditions and social structures of

ancient

tribes, ancestors of modern industrialized urban men, and the still

existing or

recently extinct primeval men. Can we explain the evolution of some

groups and

the stagnation of others? Can we, despite the gaps, find common traits

which

will bring some understanding of social structures and political

behavior?

Different anthropological schools offer various theories but the

overall

picture of their approaches to the process of development in human

groups is as

yet not conclusive. Indeed, it would be unrealistic to try to establish

a set

of formulae of cultural regularities by which both the evolution of

Batavia

into present-day Holland and that of ancient Sumer into modern Iraq

could,

without exception, be mathematically explained.

Particular

conjunctures are of great significance in the

history of mankind, making universal generalizations difficult. People

of the

same stock in similar environments undergo different

sequences of events creating their unique historical patterns. The

prevalence of a given belief at a given time, the existence of a

certain leader

at a given conjuncture, the juxtaposition of neighboring factors in a

given

setting, exceptional natural bounties or calamities, to mention a few,

are

among possibilities which may make similar people in similar

environments look

different (not to speak of the difficulty in identifying "similar

people"

and "similar environments"). We will, then, without any pretentions

at elaborating universal formulae, try to see whether anthropological

and

sociological studies can provide us with some clues as to the nature of

human

groups which can aid us in our study of man's political behavior.[22]

The group, of course,

is not stagnant; thus, in order to

study man within his group we have to visualize its fermentations and

dynamics

in time and space. This qualification of man and his group is crucial

to

understanding political phenomena. Man in isolation or a group in

abstraction,

independent of spatial or temporal dimensions, will give us only

distorted

images. The political thinker and analyst need the behavioral continuum

within

the environment to make sense of observed phenomena. In that continuum,

to

paraphrase Hegel and Sartre, the past and the seed of the future are

present.

V.

Family and Kinship, Clan and Tribe

Researchers and

historians from Thucydides and Ssu-ma

Ch'ien[23]

to our modern anthropologists and sociologists seem to agree on the

clannish

and familial texture of early human groups and its extension into

modern times.

Even at our present social evolution, group members identify themselves

through

their lineage or kinship. In the primeval group the relationship

between the

social and political structures and clan and family ties is more

obvious and

easier to trace. We know from the historical accounts and

anthropological

studies that, for example, lineage and kinship serve as vehicles for

passage of

rights and status within the group.[24] We can

therefore gain insight by examining

primeval groups.[25]

At the primeval stage

we may conceive of groups as small

as a nuclear family, i.e., a male and female and their immediate

progeniture,

or small extended families composed of immediate generations, their

mates and

progeniture, with limited environmental possibilities permitting the

development of intricate social organizations. Such groups may remain

primeval

because scarce and sparse subsistence possibilities require constant

splitting

of the groups into self-sufficient nuclear units.[26]

Unless they eventually grow into bigger, more complex and stable

entities, they

will present a life pattern showing little social specialization

wherein

political factors can be distinguished from other aspects of group life.[27] This does not mean, however, that political

structure is totally absent. Indeed, even within such a group the

combination

of affectional and functional relations will establish the roles and

responsibilities of the members. For example, patriarchal or

matriarchal

structures may provide the decision-making machineries.[28]

Where conditions

permit it in terms of economy or require

it in terms of security, the group may remain together and grow, either

in one

locale or through migration. As their number increases, group members

will

identify more with those closer to them than with others. Association

into a

closer circle of persons in the course of socialization will permit the

group

member to identify himself within a subgroup. The subgroup may be an

extended

family, itself the offshoot of a nuclear family with segmentary

unilineal

system of lineage--matrilineal or patrilineal--or it may be of a

kinship nature

along transient, bilateral, consanguine family patterns.[29] Kinship, however, does not always remain at

the stage of blood relationship and may become a social artifact.[30] Kinship terms and behavior may develop among

persons with no known genealogical relationship but close social

contact.[31] This segmental closeness and kinship serve

as the social and political basis of identification in the form of a

clan

within a larger group.[32]

The growth in size may

not necessarily be accompanied by

a diversification of functions. The division of labor may remain simple

with

functions distinguished only along the sex and age lines--i.e., a child

does

what every other child does, and once mature does what every other

woman or man

is expected to do.[33] Durkheim identified such clan-base groups as

segmental

in order to indicate

their formation by the repetition of Zike aggregates in them, analogous

to the

rings of an earthworm, and we say of this elementary aggregate that it

is a

clan, because this word well expresses its mixed nature, at once

familial and

political.[34]

This stage of group

development may be passing or

lasting, depending on such factors as ecological conditions, contact

with other

groups and environments, population growth and density. The group may

retain a

subsistence economy, as have many primeval folk societies recently

studied. At

this level, the economic independence of the group's various clans and

family

units on the one hand, and the integrated dependence of the individuals

on

their family and the clan on the other hand, serve as premises for the

group's

social structure. A brief examination of the affectional and functional

dimensions which provide for and regulate the basic drives of clan

members

under such conditions will further our political analysis.

In the clan, familial

and kinship identifications which

are immanent, affectionally speaking, are converted into functional

instruments

to such an extent that the only premise of the individual's affectional

ties is

his clan as a whole, and his relations with other members of the clan

and other

clans are left to the functional arrangements provided by the clan's

rules. The

clan regulates even such institutions as marriage, allowing little

leeway for

personal choice of mate. In the words of Redfield:

On the

whole, zee many think of

the family among folk peoples as made up of persons consanguinely

connected.

Marriage is, in comparison with what tae in our society directly

experience, an

incident in the life of the individual who is born, brought up, and

dies within

his blood kinsmen. In such a society romantic love can hardly be

elevated to a

major principle.[35]

Sexual union may also

serve as a tool for intergroup

relations. Thus, according to Sahlins:

Sexual

attraction remains a

determinant of human sociability. But it has become subordinated to the

search

for food, to economics. A most significant advance of early cultural

society

was the strict repression and canalization of sex, through the incest

tabu, in

favor of the expansion of kinship, and thus mutual aid relations.

Primate

sexuality is utilized in human society to reinforce

bonds of economic and to a lesser extent, defensive alliance.[36]

The tight sense of

belonging in such a group reduces the

"individuality" of the group members. A member will be part not only

of a group identifiable in a given place or time or for a specific

purpose, but

also of a continuum of kinship constellation changing little its way of

life

from one generation to another. Life does not follow a pattern of

biological

causality, but a pattern of behavior handed down by successive

generations--a

tradition. Asking the reason for a given rite or ceremony,

anthropologists and

sociologists may often have been answered by the clansman that things

are done

that way because the ancestors did them that way.[37]

The subsistence

economy and integrated kinship structure

do not lend themselves to elaborate, long-term, intra-clan power

conflicts, as

they would constitute a contradiction in terms, disintegrating the

basic unity

required for a clan to cohere. Whatever distinction of right, property

and status

exist are part and parcel of the kinship ties regulated through

deep-rooted

customs and beliefs. A subsistence economy cannot permit much

diversified and

complex stratification.[38] The phenonomen is not particular to primeval

groups. Even subsistence economics involving groups of people who have

previously belonged to complex urban civilizations tend to reduce their

power

structures to a bare minimum.[39]

Excitement and

challenge drives can be expressed through

the interaction of the whole group with its environing factors,

including war

expeditions which may involve not only the warriors or the act of war,

but long

and complex preparations and rituals requiring every member to

participate.[40] As for the quest for the unknown, it will be

omnipresent in the forces of nature and will be of direct concern to

the

group's survival. It will need to be explained, appeased or invoked for

help

and for justification of rules of conduct. Tradition and belief merge

and

emerge as the manifestations of group relationship to the unknown. In

the words

of Redfield, "Gaining a livelihood takes support from religions, and

the

.relations of men to men are justified in the conceptions held of the

supernatural world or in some other aspect of the culture."[41] The caprices of nature call for magic

rituals. Malinowski tells us of the islanders who have elaborate

rituals for

their fishing expeditions on the open sea but not for fishing in the

inland

lagoon where hazards are few.[42] The complexities of the rituals in relation

to the supernatural depend on the group's possibilities in its

interaction with

the environment. Thus, for example, the Arctic Eskimos devote

relatively less

time and elaboration to supernaturalism because the taxing conditions

of their

environment demand full employment of both individual and group

resources

simply for survival.[43] In other words, while the drive to relate to

the supernatural is universal, and while at the primeval stage it may

constitute the basic cohesive fabric of the human group, rituals and

exercises

connected with it are not necessarily most elaborate at the primeval

level.

They may, on the contrary, become more complex as the group develops

toward a

certain stage of "civilization." The shaman or the chief who may have

been given his position according to some traditional belief (God,

heaven or

the spirit of the ancestors), may find few possibilities or little

point in

expanding his power (which, under certain circumstances, may already be

total)

in a subsistence economy which does not yield appreciable surplus.

Indeed, as

we shall see later, the nature of the economy is among the major

factors

contributing to the stratification and complex political organization

of the

group and to the elaboration of rituals.

Finally, in the

integrated clan situation where man's

physiological needs are regulated through functional relationships and

his

affectional relationships are immanent and undistinguishable from the

group, no

manifestly identifiable, distinct political institutions regulate the

sociological needs of group members. Liberty, order and justice are

those of

the clan: "A member belongs to the clan, he is not his own, if he is

wronged they will right him; if he does wrong the responsibility is

shared by

them."[44]

Hoebel

tells us, for example, of the Eskimo arrangements whereby a deviant who

repeatedly breaches the tribe's rules is liquidated by an executioner

appointed

by the group.[45]

Kinship and clan

characteristics gain particular

significance for our analysis as they develop into more

politico-economic

tribal phenomena. While kinship and clan serve generally as the

cornerstones of

tribal structures, tribal arrangements can in turn provide bases for

many of

the more complex political realities in both traditional and modern

societies;

for, where politics is the authoritative allocation of values, the

tribe is an

appropriate context for understanding it.

As a term, "tribe"

encompasses social,

political and economic attribution,

distribution and retribution. (The

Latin origins of tribe,

tribute, attribute, distribute and retribute are tribus

and tribuere,

meaning "lot" and "allotment.") The identification of a

tribe and its members assigns them their rights and obligations vis-`a-vis themselves and other tribes.

The tribal distinctions recognize, beyond kinship and clan, the

economic

spheres --in the primeval sense, that is, including not only families

and clans

but their dependencies, such as slaves or adopted strangers, and in

most cases

their territories. Tribal arrangements permit distribution of tasks as

well as

attribution of the harvest (including such products as the booty in a

raid or

the spoils of war). Tribal organization is patterned on the affectional

functional dimension of group relations. The individual members of the

tribe

are thus provided with identity and material security, both of which

will, of

course, claim the member's allegiance and loyalty. The tribal

constellation of

identity, security, allegiance and loyalty constitutes a whole for

political

and economic organization. Because of its high potentials for fusing

the

affectional and the functional, the tribe and the characteristics it

engenders

survive even when the society develops into more complex and

functionally

organized economic and political entities.

Even though we may not

refer to them specifically, the

clannish and tribal dimensions of group organization will be reflected

in our

later discussions and should be present in the reader's mind, not only

when we

examine communal and social patterns or traditional cultures, but also

when we

deal with modern societies and political institutions. The Watergate

case--notably the emphasis of some presidential aides on loyalty, and

the

efforts at the highest executive levels to provide assistance and funds

for the

legal defense and family support of the Watergate burglars--showed to

what

extent the constellation of identity, security, allegiance and loyalty

can

counterbalance--or rather counter--institutions based on strictly

functional,

legal and political premises.

VI.

From Simpler to More Complex Groups

Our study of the

primeval group so far has covered

certain basic social arrangements which, in the absence of elaborate

political

structures, regulate group life. The affectional and functional

relationships

among members merge to make the primeval group an immanent whole, not

the

result of a contractual association or a pact as Hobbes, Rousseau and

Locke

conceived it. A glance at more complex, politically organized societies

makes

us realize that the phenomena discussed in the context of primeval

groups,

although sometimes differently manifested, are at the origin of many

modern

social arrangements and influence our political behavior, processes and

institutions.

In many modern

systems, lineage and kinship do not seem

sufficient bases for transference of position and status. Yet,

hereditary

monarchies aside, lineage is still the recognized channel for wealth

through

heritage (even i.^. socialist political systems striving for

communism). Where

wealth can buy rights and privileges, those rights and privileges may

be

indirectly transferred along with the bequest of wealth. As for

position or

status, even where inheritance is not a recognized channel for their.

transfer,

the process of socialization within the family or the clan helps

maintain an

appreciable degree of continuity in social class, occupation, position

and

status from one generation to another.[46]

Regarding tradition,

we may point out that in their

everyday life, many still justify behaving as they do for the same

reason that

the Aborigines of Central Australia gave Strehlow, because their

forefathers

acted that way. Not only do our fathers' deeds influence our feasts,

ceremonies

and private behavior, but they also seem to influence our political

behavior,

such as party affiliation.[47]

Turning to religion

and myth, we can hardly make our

point better than to invoke Malinowski's words:

Myth is

to the savage what, to a

fully believing Christian, is the Biblical story of Creation, of the

Fall, of

the Redemption by Christ's Sacrifice on the Cross. As our sacred story

lives in

our ritual, in our morality, as it governs our faith and controls our

conduct,

even so does his myth for the savage.[48]

Thus, certain

phenomena are common to group life, at both

the primeval and complex modern urban levels.[49] While at

the primeval level we can see that

such phenomena as lineage, kinship and clan bonds, tradition and belief

constitute enough of a social fabric for the group's rudimentary and

simple

political needs, we will have to examine them in the context of

differentiated

and stratified groups to see whether, in the process of development,

the nature

and role of these phenomena are altered and whether new structures

evolve to

meet new social conditions.

Cumulative

Economy

In the last sections

we outlined a general pattern of

group structure which, to be sure, had its variables. But on the basis

of

archeological, anthropological, historical and sociological studies,

our

general pattern is broadly applicable to the social structures of early

bands of

hunters and food gatherers as well as those of primeval groups which

have

survived to our day with a subsistence economy. Our model can cover

some 30,000

years--from the early Cro-Magnons in the valley of Vezere in France to

the

ancestors of the ancient Greeks. Thucydides describes the early

settlements in

the Greek peninsula in these terms:

There

was no commerce, and they

[the Greeks] could not safely hold intercourse with one another by land

or sea.

The several peoples cultivated their own soil just enough to obtain a

subsistence from it. But they had no accumulations of wealth and did

not plant

the ground; partly because they had no walls.[50]

From this description

let us retain certain factors which

will be useful for our later analysis, namely the facts that in their

subsistence economy they had no exchange,

they did not plant their land, had no

accumulation of wealth and had no walls.

There is evidence of a

turning point in the history of

man starting sometime between twelve thousand and five thousand years

back--the

beginning of "civilization."[51]

Sometime around then the general patterns suggested in the last section

for

group structures at the subsistence level of economy became inadequate

to

explain more intricate social phenomena. According to our present

archeological

knowledge, in at least four areas of the earth--notably the valleys of

the Nile

in Egypt, the Euphrates and Tigris in Mesopotamia, the Indus in India

and the

Yellow River in China--man finally evolved from food-gatherer and

hunter into

farmer and shepherd.

The evolution implies

the domestication of food sources.[52] But is

also implies the need for more

elaborate social structures, as exchange and accumulation of stock will

require

specialization. In other words, it needs a cumulative economy. We use

the term

"cumulative economy" rather than "surplus economy" because

the simple fact of going beyond subsistence and producing surplus is

not

sufficient for social evolution. Malinowski speaks of the Trobriand

Islanders who,

before the possibility of exchange arose, were letting their surplus

production

rot unconsumed.[53] Further, while demographic growth influences

the development of complex social and political structures, the

determinant

factor for such development seems to be the nature of the group's

economy.

Thus, regarding the Logi and Nuer tribes of Africa, which may attain

units of

45,000 members divided into clans, subclans and lineages without

elaborate

political structures, we are told:

Theirs

is mainly a subsistence

economy with a rudimentary differentiation of productive labour and

with no

machinery for the accumulation of wealth in the form of commercial or

industrial capital. If wealth is accumulated it takes the form of

consumption

goods and amenities or is used for the support of additional

dependents. Hence

it tends to be rapidly dissipated again and does not give rise to

permanent

class divisions.[54]

Elsewhere, Redfield

tells us: "Within the ideal folk

society members are bound by religious and kinship ties, and there is

no place

for the motive of commercial gain. There is no money and nothing is

measured by

any such common denominator of value."[55]

In its early stages a

cumulative economy may be a

permanent village-farming settlement. But even before "urbanization,"

this cumulative economy must provide for collection, storage,

distribution and

exchange of the means of livelihood for the group members and, must

make an

exchangeable and convertible surplus possible. The process will no

longer be

hand-to-mouth.

Functional

Social Differentiation

The arrangements for a

cumulative economy require

specialization, notably for the group's material and social

organization and

for control of its surplus. On the way to "civilization,"[56]

this social organization liberates some of the labor force from direct

food-producing tasks and permits the development of arts and crafts.

The

released productive forces are used for building, irrigation projects,

tool

production, and other social functions. Differentiation of labor and

exchange

of the diversified products require social frames of reference making

intercourse feasible. The early Sumerians established commercial and

banking

practices, fixed prices and wages by law, standardized weights and

measures and

codified civil law in writing. The implementation of these social

functions

require specialization and control. Among these is the specialization

to control. In order to make exchange and

convertibility of products and services possible, value

judgments--conscious or

unconscious--will have to be made as to their relative importance for

the group

or parts of the group. I say "parts of the group" because, while at

the primeval level, family, clan or tribe is an immanent whole, in the

differentiated

cumulative and urban society certain parts of the group, with different

degrees

of influence and control and diversified interests, may evaluate the

importance

of different functions differently.

Differentiation and

specialization involve social

stratification. We may assume that those in effective control, whether

holding

public offices and political positions directly or controlling them

through

intermediaries, will be instrumental in establishing social strata and

will,

reasonably enough, place their own position and status high on the

scale. This

should not necessarily be understood or misunderstood as an imposition

on the

other components of the group. It is a social phenomenon arising from

group

fermentations and dynamics. The more those involved consent to a

particular set

of strata, the more the group will have cohesion and harmony, though

cohesion

and harmony do not imply absolute equality and justice. As we noted at

the end

of Chapter Two, both the rulers and the ruled must recognize the

validity of

the prevailing norms for the group to cohere and stabilize.

Similarly, the

gradation of the social strata will not

follow an absolute criterion or an objective mathematical

rationale--impossible

to conceive or formulate anyway--but will depend on the arrangements of

the

power structure. Thus, while the cumulative society draws its power

from the

products and labor of the farmers, shepherds and workers, it will not

necessarily accord them a prominent social position. For the pharaohs

of Egypt,

the priests of Sumer, the Chou princes of China, as well as modern

power

holders (industrial managers, political and economic administrators),

those who

help maintain the social structure, i.e., the soldiers and those who

help equip

them, just to name a few specialists, are more instrumental and

therefore

occupy a more prominent position than the laborers in the fields,

pastures and

workshops. Unless these laborers organize themselves into power

complexes such

as unions (which themselves obey the laws of the power complex), they

will

become instruments rather than instrumental.

As the cumulative

economy grows, bringing about a dense

and heterogeneous population and a more complex society, the functional

character of specialization will result in less personal relationships

among

the group members in the differentiated segments. As we noticed, in

smaller,

less complex groups the affectional relations intertwine with the

functional

parameters, but as the society evolves the loci of affectional and

functional

relations may be transformed and displaced. The affectional factors may

be

weakened in certain relationships and shifted. This should not

necessarily

imply that the social structures as a whole will unconditionally move

away from

affectional relations and that functional organization will tend

toward its

extremes of the state-of-nature or mechanical rationales we discussed

earlier.

For the human group to hold together, affectional relationships must

anchor the

functional arrangements. The drive for contact comfort, the need to

belong, and

nonrational feelings are basic human characteristics. Indeed, while in

the

primeval state they were satisfied through the immanent nature of the

clan or

tribe which made affectional and functional relations a whole, in the

more

impersonal functional arrangements of urbanized cultures they may

receive new

emphasis, both to meet the needs of the individual members of the group

and to

give the group its particular human texture.

Affectional

Communal Identification

We noted earlier that

for socialization, the group uses

man's thinking and communicating faculties by inculcating them with

terms of

reference which permit the group members to understand each other. From

his

early years the individual is usually exposed to a particular way of

life and a

language with which he identifies himself. He also identifies with

those who

share with him his particular way of life and language, which they have

in fact

inculcated in him. These common premises develop a sense of belonging

and an

understanding beyond simple exchange and communication, involving

affectional

relationships in whose context the group members draw satisfaction from

their

mutual familiarity, from understanding each other and from their

similarity of

outlook. Not only do the group members communicate, but they commune as well, interacting in

affectional relationship. But to commune refers to more than the nature

of the

relationship among group members; it also qualifies their position in

relation

to those who are not considered part of their group. Munio,

and its derivative communio,

the Latin origin of the word "commune," means to fortify, to enclose,

to secure, to build together. The wall

in our earlier quote from Thucydides meant not only the walls of the

city but

also a wall for inner security. Thus, in addition to sharing norms and

values

with each other, the members of the group, in their togetherness as

contrasted

with others, find their rampart. It will be their

commune, within which they will commune: their community.

These communal

feelings develop in primeval groups as well

as within complex societies. Of the folk societies Redfield says,

Communicating

intimately with

each other, each member of the group has a strong claim on the

sympathies of

the others. Moreover, against such knowledge as they have of societies

other

than their own, they emphasize their own mutual likeness and value

themselves

as compared with others. They say of themselves 'use' as against all

others,

who are ‘they.’[57]

This dichotomy between

"we" and

"they" is clearer at the stage of folk societies where, because of

their segmental economy, clans and tribes can be distinct and their

intercourse

and interpenetration be regulated by strict rules. As we move to more

complex

social structures, communal feelings no longer necessarily imply

close-knit

units and mutual personal knowledge of every fellow member. The

likeness and

"belonging" which provide communal bonds will be relative and in

contradistinction to the complex environment. Members of a particular

group

will share enough likenesses and be conscious of them to spot a

"stranger" in the way he walks, talks, dresses, eats, behaves,

believes or "thinks." The communal identification in a more complex

society, as distinct from folk groups, should be conceived in terms of

particular social characteristics rather than physical nearness. In a

macrocosmic sense, we may also identify larger, thinly homogeneous

groups as

distinct from each other: we may speak of the Atlantic Community. Not

that the

Sicilian shepherd necessarily communes with the Norwegian farmer, but

they do

have some values and standards in common as distinguishable from, say,

the

South Asian community. When we look closer into each of these

macrocosmic

"communities," we will notice that while they do not, as such,

qualify as a community the way a village parish would, they

nevertheless have a

common thread of identity. For example, both the Sicilian shepherd and

the

Norwegian farmer qualify themselves as European and Christian. But it

may be

better that they never meet face-to-face, for if they did they might

realize

that the Sicilian shepherd probably has more in common with a North

African

shepherd, and the Norwegian farmer more in common with a North Dakota

farmer.

The knowledge of both of these facts, however, is important to the

political scientist

or the politician--for example, when he wants to use European and

Christian

community feelings in support of a project for a European alliance. As

an Asian

statesman exclaims, "We Asians..." he touches a key which may vibrate

the solidarity of the Shinto imperial Japanese, the Lamaist theocratic

Tibetan,

and the republican Hindu Indian.

This "we" as against

"they" is based

on the affectional dimension of individual and group relationships.

Affectional

bonds run through the fiber of human social life. There again, our

general

classification of relationships into affectional and functional is

instrumental

in delineating a community from within the society--an otherwise

difficult

sociological dissection, as illustrated in such pioneer works as that

of Toennies

where Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft

(community and society) cut

across each other.[58] Similar to primary and secondary groups,

community and society are not tight structural definitions but can be

better

conceptualized through the affectional and functional nature of the

relations

among their members.

Differentiation

and

Identification, Functional and Affectional

The "we" as against

"they" feelings

which develop affectionally bring about, within the group, dimensions

of

identification and differentiation in addition to the functional ones

discussed

in the context of cumulative economy. While social stratifications in

the

complex group are based on functional specialities, a.different type of

stratification based on affectional relations can be recognized within

and by

the group. Generally, though by no means exclusively, affectional

relationships

develop in the context of kinship patterns which evolve as the group

gains

complexity and heterogeneity. These relations may develop at certain

stages of

contact and closeness and continue through the social strata even when

such

contacts and closeness have ceased. The longest-lasting of these

affectional

relations so far has been and still remains within the family, although

the

highly mobile and rapidly changing industrial and modern society is

diminishing

the role of the family as the catalyst of these relations. Further, in

school

among members of the same generation, in the factory, the office or the

field

among members of the same profession, in the church among followers of

the same

confession, and in the society at large among members of the same

ethnic group,

affectional relations develop and permeate the members' functional

behavior.

The affectional

influence on the functional develops not

only out of direct experiences but also out of a general attitudinal

pattern.

The former farmer who becomes a political executive may feel

affectionally more

at ease with a new collaborator who gives signs of a rural temperament

(although he may not be a farmer) than with a functionally more

efficient

collaborator with an urban temperament whom he may consider an

irritation and a

threat. The affectional, as we noticed earlier, may have a positive or

a

negative charge. For example, our farmer may have developed an aversion

towards

his former environment and may shun whatever reminds him of it. Or we

may find

that, although the former farmer identifies more with a person of rural

temperament, he has to opt for the collaborator with an urban

temperament who

can complement his own dimensions--a symbiotic situation. On the other

hand, he

may opt for the rural character with whom he identifies more and with

whom he

can work better because of their common wave length, but who may in

fact become

a competitor--a commensal situation (that is, eating from the same

table).[59] As the affectional develops within the

functional--and when positive, facilitates it--one may also pretend

certain

affections to further functional ends. The politician who runs for

office

claims broad identity with diverse segments of the population.

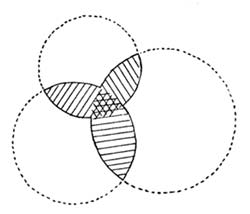

The heterogeneous

complex society thus provides

diversified areas of contact and cooperation in the context of which

equally

diversified functional and affectional differentiations and

identifications

become both cause and effect of the group's social texture. There will

be

circumscription, overlapping, interlocation, interaction, transaction,

interpenetration or encompassment within and among the groups,

depending on the

criteria used to identify them. The individual in the society draws his

social

identity from these fermentations and dynamics of the different groups

of

which he is a part and to whose impact he is exposed.

VII.

The Range of Group Identity

As the individual is

exposed to further norms and absorbs

them, this range of identity widens: from the family to the clan, from

the clan

to the tribe, or from the school to the college, from the college to

the

professional circle, and so on. The process has an accelerative phase,

the

limits of which change according to the individual and the environment,

and

during which the thrust for satisfaction, curiosity, and the search for

the

unknown move the individual to look for exposure to new dimensions. But

it also

has a decelerative phase when the individual feels his security

endangered by

further exposure and dispersion. The values and norms with which he

identifies

constitute a nucleus wherein he feels mentally at home and wants

neither to

reject them nor to be rejected by them. When he feels distant from them

he will

block himself to alien encroachment on them.

Of course, the

rigidity of the nucleus and the radius of

identity are flexible for both the individual and his group, depending

on

environmental conditions, which may be more or less conducive to

exposure. We

saw earlier that at the level of a primeval group with a simple

subsistence

economy and little contact with a complex environment, we could

visualize a

rather uniform pattern of identification within the group where the

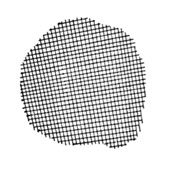

shell and

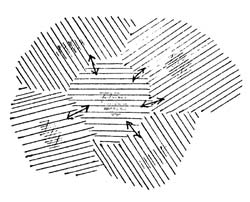

the core were the clan and the tribe itself (see Fig. 3.02).

Fig.

3.02

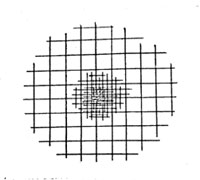

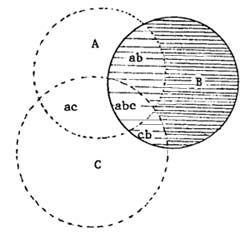

As relations among

group members become more complex,

functional and impersonal in the cumulative economy, the individual

becomes

more conscious of his immediate environment on which he can fall back

for

affectional identification and mental security. While the borderline or

the

shell of the group (or now rather the subgroup) may become less clear,

the

nucleus or the core should consolidate if the group is to continue to

be

identified as such--and the individual to be identified with it (Fig.

3.03).

Fig.

3.03

This process will not

only help identify subgroups and

their members, but provide stability and continuity in the larger

encompassing

group. Some vehicle must carry power, position and property through the

social

structure, and the vehicle has been group identification. The family

and the

clan can provide one such identification. The hereditary monarchy

develops not

only because of the paternal attachment of the sovereign to his

progeniture--an

important factor, to be sure--but also because of the likelihood that

as the

society grows more complex, the kind of closeness that can provide for

the

passage of kingly qualities from one generation to another is better

provided

in a filial relationship. From the Chinese traditional accounts we

learn that

on the death of Yu about 2000 B.C., the people insisted on recognizing

his son

as their sovereign, rejecting his minister, I, whom Yu had entrusted

with his

power. Thus began the first Chinese dynasty of Hsia.[60] This recognition of filial identification

for social stability and continuity can better be realized when the

above

account is complemented by the following passage which Han Fei Tzu

attributes

to Confucius:

. . .

there was a man of Lu, who

followed the ruler to war... fought three battles, and ran away thrice.

When

Chung-ni [Confucius] asked him his reason, he replied: 'I have an old

father.

Should I die, nobody would take care of him.' So Chung-ni regarded him

as a man