|

|

CHAPTER 1 CACO ERGO SUM

According to statistics 98 percent

of humanity believes in some kind of supernatural

power. Indeed, even those

who attempted to distinguish the species as a thinking

animal were not free from the ascendancy of the

gods. Plato's androgynes, those creatures that

were so intelligent and agile that they threatened the

gods, were created by the gods. And the gods

proceeded to cut each of them into two halves to make

a woman and a man out of each, each half eternally

seeking the other half, leaving the gods in peace.[1] Descartes posited his “I

think therefore I am” as a proof for the existence of

God. His attempt to

envelope his rational method in God’s grace was in a

large part genuine and was not motivated only to avoid

the wrath of the church and a fate similar to those of

Giordano Bruno or Galileo.[2] The high percentage of believers

and the acrobatics of thinkers to wrap their thoughts

in the divine are intriguing. Some

suggest that the idea of God may actually be located

in the brain. According to recent research,

increased neural activity in the temporal lobes would

trigger the ecstasy of being in the presence of God –

epilepsy causes a keener sense of that.[3] Increased activity in the

frontal lobe associated with decreased activity in the

parietal lobule could lead to the ultimate goal of

transcendental meditation’s freedom from time and

space.[4]

These are presently results of clinical

experimentations. If they were definitively

established we could reduce the idea of God to

electro-chemical activities in human brain. We would then classify man's

need to believe in supernatural powers along other

physiological and psychological drives, and wonder

about the two percent of humanity who do not manifest

that urge. Posing the question about the two

percent, however, misses a major point: that

most of the 98% who do believe, do not believe in God

because they experience mild epileptic strokes or

meditative bliss. They

believe in God because the society, parents and peers

channel their fear and awe of the unknown through

institutionalized religions in order to appease their

fear and make them socially functional.[5] It is interesting to note

that even those who do the neuroscientific experiments

make a point of expressing their faith in God. And religious institutions

make sure to keep their flock within bounds – the

conference on the neuroscientific experiment on

transcendental meditation was sponsored by religiously

oriented Templeton Foundation. For

most, God is not ecstasy or Nirvana but the rampart

which gives them security at the edge of the abyss. Being among the two percent,

I do have to search the unknown.

I do lack the fear and awe of the

believer. I either understand or I don’t. I don’t believe. Where I don’t understand I seek to

learn in order to understand. St.

Augustine’s believing before understanding is a

cop-out. I am among the two percent of

non-believers probably because I was brought up that

way – which proves my point about the influence of the

environment and parents on one’s approach to the

unknown. I recall coming

home from school one day and telling my father about

the "Ascension." He asked

me to raise my feet. I lifted one. He said: "No,

lift both!" I said I can’t, I’ll fall. He

said if you cannot lift both feet at once ten

centimeters off the ground, how did Jesus lift off to

go to heaven? Later in life, I learned that my

father’s question was not that original.

According to Moslem tales, it is the question

Abu Jahl put to Mohammad after the latter recounted

his night journey -- “The Israelites” Surah – a

tale which is said to have generated the myth of

“Boraq”, the fair-faced winged horse which transported

Mohammad. It is not that I was told to reject

religious dogma off-hand, but to question. Indeed, I was reprimanded

when I did not question and did not ask the how and

why of things. I enjoyed reading the different

versions of the Bible, whether Judaic, Christian or

Moslem and found them imaginative.

They were great stories. The Vedic tales were

riveting. But I was

always reminded that believing in their or any other

religion's supernatural pronouncements would become

blinders in the search, and magnify the fear and awe,

of the unknown.

Granted, a part of the fear and the awe

is used to inculcate patterns of behavior for

moral and ethical conduct, but the greater part is

for the perpetuation of the religious dogma and

the primacy and control by the religious

institutions. No other cause has made human beings

kill each other more than religion. It was with that perspective and

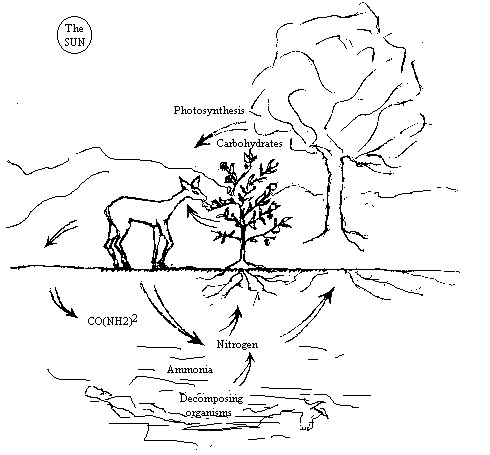

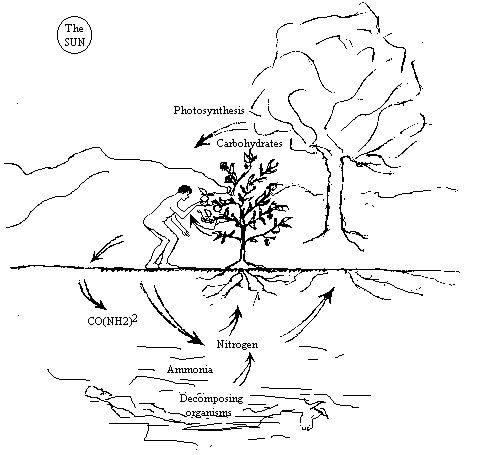

the question of being on my mind that I was looking at

the drawing in my biology book illustrating the role

of nitrogen and carbonic acid cycles in nature.

It showed a deer standing on the grass among the

trees; grazing, digesting and excreting –

re-establishing the balance of the ecological chain by

providing fertilizer and nutrients to grow the food it

eats.

I was a link in the ecological

chain. The first undeniable function of man

within the context of his environment is to turn the

foodstuff provided for him by nature into shit. As I eat, digest and

excrete, I fertilize the plants.

One organism among others meant to contribute

to the balance of nature. And

what an organism! A

self-perpetuating machine with its own reproductive

organs. No factories

needed! Something man has

not yet managed to achieve through the machines of his

making. As man breathes the air to produce

carbon dioxide, drinks and eats to produce urine and

feces, the process provides him energy to breathe

more, drink more, eat more and to reproduce. In other words in the

ecological complex, the energy the animal produces by

processing nutrients is used for the drive to further

search for more raw material in order to produce the

finished product. And when the machine is used up, it

disintegrates and is recycled back into the process –

sooner than later if not hampered by a multi-layer

casket. The reason for my

existence, then, was obvious. In

the cycle of nature I was a processor of food, a

shit-making machine: Caco ergo sum – I

shit therefore I am. In their search for raw material,

different organisms adapt to different processes

depending on their instinctive and intellectual

complexity. Organisms which man calls protozoa such as

amoebae are examples of direct processes of intake,

output, reproduction and decay. In

more complex organisms the process involves more

indirect interaction with the environment. The squirrel gathers and

stores the nuts, ants grow mushrooms and, of course,

man goes farther and processes the raw material to

different degrees before taking it into his organism

for final processing. The

chain of man's contact with nature is thus much

farther stretched than simple cells and distances him

from direct understanding of his role in the universe. That may be the reason why

man has the drive to search and fear the unknown. Does the deer also ask the

question: “What is it all

about?” And what about

the amoebae? Does the amoebae ask the question “am I ?”

– Is it conscious of being? I

ask the question because I think I am conscious of

being – as distinct from not being.

If I were not conscious of being, would I be?

My being may well be due to my consciousness of

being. Is it consciousness that

is? Is consciousness

different from being? Can

the amoebae be without being conscious of being? Or can it be conscious

without being conscious of being?

Conscious of what? Conscious

of the universal without being conscious of being. With these questions about

the different states of amoebae's conscious in mind, I

pose the problem at three levels:

1. Is the amoebae conscious of its

own being? In other words, is it “self-conscious”? 2. Is the amoebae conscious of its

being within its environment? Of being

there. Of being-in-the-world

– Dasein? 3. Is

the amoebae's consciousness of its environment

confounded in the universal? To the extent that

the amoebae does not question its own being and

being-in-the world, is it conscious of being one with

the universe? Does it need to? These three levels of consciousness

refer to the three propositions we have touched upon

so far, namely: 1. the image of God (man's quest to

commune with the universe), 2.

I think therefore I am (consciousness) and 3. I

shit therefore I am (partaking in the cycle of being

within the environment). The universe, consciousness,

and the self within the environment evidently need to

be further explored.[6] *

* * Addendum

Some, exposed to my idea

of human beings as "shit-making machines," have

expressed concern about the consequences of

letting the species loose from the wrath of God. Before proceeding any

farther, I would like to refer them to my “Moral

Code” which would eventually be the conclusion

of this essay: Moral

Code The

moral code of behavior inspired by religion but

liberated from its hocus-pocus, superstition and

fanaticism could be quite succinct.

It would boil down to:

* Don’t do unto others what you don’t want them to do to you.

It

sums up and broadens the Ten Commandments. It does not cover only

those acts enumerated in the Ten Commandments, but

also disagreeable behaviors such as

aggressiveness, harsh words, disorderly conduct or

sloppiness. And it

calls on you to apply it to every body, not only

your neighbors. You

should not do to anybody what you

don’t want him or her to do to you.

It

does not need Moses to talk to the burning bush

and come down with the tablets.

It is reciprocal common sense behavior that

would create mutual trust and make harmonious

social life possible. It

is simply in your own self-interest: for your

comfort and peace of mind. And don’t go about “doing onto others what

you want them to do to you.”

As George Bernard Shaw put it: “they may

not like it.” It is

misplaced altruism, intrusive and

counter-intuitive.

It

is the introspective active side of the first

premise of not doing unto others what you don’t

want them to do to you. Without

being intrusive, be positively good in your

intercourse with others. It

reflects the Zoroastrian tenets of Pendare

neek, Kerdare

neek, Goftare

neek

without the need for fire temples. In his Spiritual

Exercises, Ignacio de Loyola, the founder

of Jesuit branch of Christianity, enumerated

them as precepts for the “General Examination of

Conscience.” * Step one step out of

yourself, turn around and examine your

self.

It

permits you to look inside yourself and see

whether you are not inadvertently doing to

others what you don’t want them to do to you,

and whether your thoughts, deeds and speeches

are good.

It

is a Sufi precept, but you don’t have to be a

whirling Dervish to exercise it.

* * *

©1999 Anoush Khoshkish

All rights reserved [1]

Plato, The Symposium. [2] Descartes, Méditations II, III

etc. [3] Jeffrey L. Saver & John Rabin, “The neural substrates of religious experience” in The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 1997, 9 pp. 498 -510; Vilayanur S. Ramachandran, San Diego. [4] Andrew M. Newberg, A Neuropsychological Analysis of Religion: Discovering Why God Won’t Go Away, paper presented at the AAAS Conference on the Neurosciences and Religion, February 10, 1998, and Eugene d’Aquili & A. M. Newberg, “Researchers find clues to religious euphoria” in the University of Pennsylvania Health System Media Review, May 1998. [5]

For more on the subject see A. Khoshkish, The

Socio-Political Complex, Oxford, Pergamon

Press, 1979. pp. 23-24, 76 et

seq. [6]

I am, obviously, posing perennial philosophic

questions. In the back of my mind are such

concerns as: Hume’s causal skepticism and

discourse on natural religion. See notably his The Treatise on Human Nature, The

Natural History of Religion and Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion.

Kant’s questioning of man's capacity to move from

the understanding of the phenomena to the

conception of the noumena and the handicaps of

reason which inevitably falls into contradictions

when attempting to “think the whole”. See notably his Critique of Pure Reason. Hegel’s

treatment of consciousness and self-consciousness

in the context of reason, spirit/mind (Geist)

and religion, and conception (Begriff)

as the essence of being. See

notably his Phänomenologie des

Geistes. Husserl’s transcendental

phenomenology arguing the limitations of

Descartes’ “I think” to explain consciousness. See his Ideas. Heidegger’s ontological

approach to the question of “being” and making it

conditional to Dasein –

“being-there”, “being-in-the-world”. And Sartre’s

the transcending for-itself

consciousness, being conscious of being other than

itself, whether pre-reflective or reflective –

thetic – consciousness. See

his La Transcendance de l’Ego and

Being and Nothingness. And others. Those

familiar with these works will recognize the ideas

of these and similar philosophers, either

sustained or refuted, all along this essay. The purpose here is not

to review or regurgitate the ideas of these

thinkers but to pick up their ideas where they

left them and reflect further. The reason for this revisit

of age old inquiries is to see whether there is a

remedy for the divorce between philosophy and

science which since the nineteenth century has

handicapped human understanding, ever more

accentuated by segmentations,

compartmentalizations and specializations of

fields of inquiry and further aggravated by the

prevailing utilitarian approach of “what is it

good for?” |