|

||

|

Bio-Ethics Reflections on Political Ecology[1] A. Khoshkish We

cannot command nature except by obeying her.

Francis Bacon, NovumOrganum I - PROGRESS, POPULATION AND PRODUCTIVITY A. The Material Man, by his own

definition, is an animal living on the

planet earth. He is an omnivorous mammifer who is adapted best to a

savannah

type of climate. Except for certain physiological adaptations such as a

greater

number of perspiration glands in warmer climates or fat deposits in

colder

weather which make him more resistant to certain tolerable climatic

fluctuations (Coon, 1954), he would not have been able to survive in

many parts

of the earth. Yet man managed to explore and inhabit practically the

entire

surface of the planet, and this by artificial means, i.e., by unnatural

processes. The natural process for a naked man in the Arctic would be

to freeze

to death and in the tropics to die of exposure. Beyond gathering food

and

hunting, man used the skin and wool of his victims for warmth,

domesticated animals,

constructed shelters, and developed agriculture. Of course, the

interference of

man with nature for his survival has had its natural repercussions.

Some

species of animals have been hunted to death, while deforestation and.

erosion

of soil have turned arable lands into arid deserts and dried up rivers,

as

happened with the desert of Bahawalpur in northwestern India and the

once

mighty Hakra River flowing through it (Tinker, 1966). Nature, however, kept

man under control. Disease and

famine managed to keep man within reasonable numbers. Man himself also

gave a

hand to nature by indulging in self-extermination through wars. Malthus

called these positive checks! The fittest under the circumstances,

depending on

the situation, survived. Man had few pretensions of harnessing nature

and was

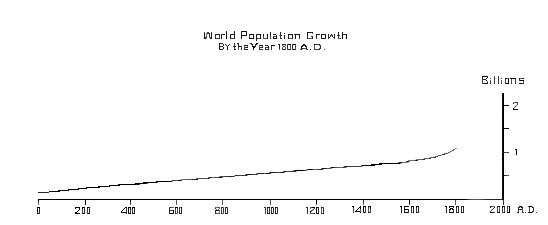

conscious of its existence and its awe. The curve of world

population growth by the year 1800

looked like this (Presiden’s Science Advisory Committee Report, 1968):

Then part of mankind

started to overdraw on nature's

deposit. Science, technology, and medicine enabled man to explore and

use

nature as a tool for progress.

"Progress towards what?" you may ask. We are in the habit of using

this word as a goal in itself. As if it had majesty of its own. In

fact, in the

last analysis progress boils down to the drive for ever better

satisfaction of

man's animal needs: to spare him from death as long as possible and

lengthen

his survival, to bring him comfort and spare him from hardship, to give

him

more leisure and satisfy his curiosity and his drives for amusement.

The

technological age made it possible for man to look for progress towards

these

ends through material well-being. Before this age,

beyond their material efforts limited by

nature, the mass of men, be they kings or serfs, searched for the

extension of

their survival and comfort, and for answer to their curiosity, in

metaphysics

rather than physics. Alchemy and magic were more psychological supports

than

material help, while Heaven secured survival after death and solaced

those who

lacked material comfort in this life. The European

industrial revolution seemed to bring with

it the Promised Land right on earth, at the beginning for the few, and

more

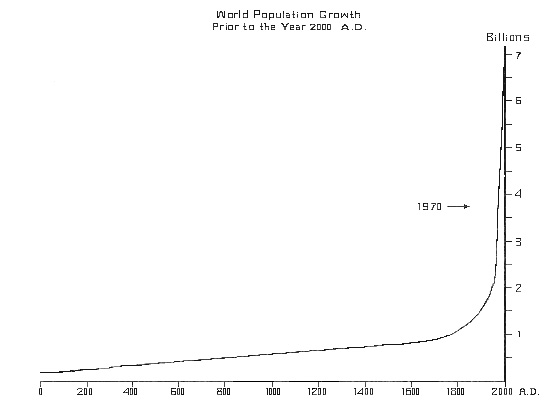

recently for the multitude. The curve of world's population growth then

became

like this (PSACR, 1968):

Nature seemed to be

there for exploitation. Its

generosity was considered as endless and its passivity the very salt of

the

earth. Viewed in this way, all progress needed was more men to exploit

nature

and to be exploited. So the growing population which was the

consequence of

progress was a welcome factor. Population meant more labor force,

bigger

markets, more profits-in short, more power! And power is of interest to

politics! Progress was the thing. It was strived for and promised.

Whether in

the name of Adam Smith or Marx, the politician promised longer and

healthier

survival, better comfort and more leisure. Through progress the

boundaries seemed unlimited. And if

injustices existed in the distribution of wealth today, they would be

remedied

tomorrow, be it through equal opportunity for all under competitive

free

enterprise or to each according to his needs under communism. B. The Ethical The revolutionary pace

of industrialization and its

social consequences brought into the forefront dimensions of ethical

concern

more related to the human conditions arising in the modern

technological world.

Whether under the banner of Christian charity or social justice, these

ethics

were to serve as vanguards against those aspects of human shortcomings

such as

the exploitation of other men, which were likely to be amplified in the

process

of progress and production. The social pattern

evolved parallel with scientific

explorations and technological development. The patriarchal and

corporative

texture of the society changed into a paradoxical combination of

egocentrism

and ethnocentrism, individualism and nationalism; one giving more

autonomy and

fluidity to the units within the group; the other creating a framework

for regimentation

and integration. Both were instrumental to progress and production in

their

economic takeoff, and to power politics, internal and external. Even

social

philosophies like communism, which preached internationalism and put

emphasis

on the communal duties rather than individual rights and incentive, had

to

revert to patriotism and recognize the need for individual initiative

and

satisfaction in order to keep progress and production, at a certain

stage,

going. Family, however,

remained the basic cell of the society.

It provided bases for control, supply and early socialization of the

population. It also provided the appropriate store for basic social and

moral

values. After all, even though progress made longer life possible, it

was

through procreation and offspring that man could secure his

continuation. And

the political system promised a better future and better education for

the

coming generations. The Malthusian theory was discredited by the

colossal

possibilities technology and science could offer. Together with apple

pie and

the flag, motherhood became one of the American trinities, while the

Soviet

Union bestowed the title of Heroine of the Union to her productive

mothers! Matter seemed to

dazzle the spirit. Religion, which has

been the harbor of hope in times of intermittent abundance, was now

giving

place to machine and technology which promised perpetual affluence. Now

on

occasions of man-made catastrophes like war did gods become momentarily

popular. The church, however, served the purpose of sanctifying the

institutions like family and procreation which complemented the new

ethics. In

some instances its basic doctrine did clash with the new trends. The

precept of

renunciation did not quite fit in with the drive for material gain, and

the concept

of loving your neighbor was not quite in tune with profitable

bargaining for

cheap labor. The church thus

compromised between blessing the useful

and overlooking the hypocritical. Some systems like the Soviets tried

to

dispense with the church altogether but encountered difficulties. They

apparently did not believe in Dostoyevsky when he said that "man cannot

bear to be without the miraculous, he will create new miracles of his

own for

himself and will worship deeds of sorcery and witchcraft, though he

might be a

hundred times over a rebel, heretic and infidel." (Dostoyevsky, 1880) Speaking of miracles,

however, progress did seem to

present one worth worshipping, and material gain did become a goal for

its own

sake. In the words of Stewart Udall, the Gross National Product became

the

American Holy Grail.[2] The

new divinity was of such a forceful impact that it

succeeded where

over two hundred years of colonization and Christian missionary work

had

failed. Moslems, Hindus, Buddhists, and Confucians in the developing

countries

were modifying and rejecting their convictions and traditions to

embrace the

gifts of western civilization in the name of progress. They were

accepting the

denomination of “developing”[3] in the technological

and

economic sense, relegating spiritual heritage to the background. After

all,

their goal, too, was longer and healthier life, more comfort, and

better

leisure. Heaven, Brahman, and Nirvana were good for times when you

could not do

better on this earth. Indeed, for a while

progress through production seemed to

be man's ultimate answer to his questions. Had mother earth been

generous

enough to give what man asked for and had she been indulgent enough to

swallow

whatever waste man threw into her, it seems that at some point man's

voracity

would have been satiated. When economic

development reaches the stage where

attractive social motivations are offered to individuals, the curve of

population growth levels off.[4] This

reduction in population growth is also due to better

education and

socialization, teaching among other things the use of contraceptives

(Notestein, Kirk and Segel, 1963). Diversification of pastimes and

entertainment is another factor, and finally, according to some

biological

theories, the protein-rich diet accompanying development reduces the

briskness of movement of reproductive cells at a certain age and

contributes to

population control (Notestein, Kirk and Segel, 1963). It seemed,

therefore,

technologically feasible to close the gap between the rates of increase

in food

demand and food production in the developing countries, thus permitting

them an

economic take off theoretically followed by leveling off of population

growth

on the basis of the criteria enumerated above.[5] II - PROGRESS,

POLLUTION AND POVERTY

A. The Material But then mother earth

had a word to say. She called for

attention. Not that nature counter-attacked. It is man's vision of

struggle that makes him think that he is at war with nature: If he only

could

see that he is part of nature and that his birth, life and decay are

natural

processes within that context. At the Conference on Man and His

Environment

organized by the U.S. National Commission for UNESCO in San Francisco

in

November 1969, we were presented with a grim picture of this reality:

Man has

found out that pesticides such as DDT are deposited in the soil and in

the

water undisolved for long periods of time, and end up in animal bodies

that he

eats. The FDA has established an interim tolerance limit of five parts

per

million of DDT compounds in the eatable fish. Recently Jack mackerels

taken in

the Pacific Ocean near Los Angeles were found to contain 10 ppm of DDT.

So were

the Coho salmon taken in Lake Michigan? The brown pelicans, which feed

on

marine fish, have been wiped out of Louisiana because the pesticides in

their

food thinned the shell of their eggs to the point of not being

hatchable

(Risebrough, 1969). At the same time the pests for whom the pesticides

and

insecticides were originally fabricated are becoming more and more

immune to

them. In 1963 fifty times more DDT was required, as compared to 1961,

to

control insect pests in the cotton fields of Texas (Commoner, 1969).

Very soon

the fat American may no more go on a diet safely because the DDT

deposit in his

fat may poison him (Ehrlich, 1968). The 10 to 15 per cent

increase in the minute amount of

carbon dioxide in the atmosphere since 1900 has caused surface

temperatures to

rise 0.2°C and the temperature in the stratosphere to decrease by some

2.0°C

(Malone, 1969). In the United States we produced a yearly amount of 125

million

tons of air pollutants, including some 65 million tons of carbon

monoxide, 23

million tons of sulfur oxides, 8 million tons of nitrogen oxides (Waste

Management and Control, 1966). The emission of S02 will

increase by

75 per cent in 1980 and another 75 per cent by the year 2000 (Malone,

1969). As

much as 100 million tons of oil enter the ocean through spillage or

wastage

every year, and accidents like the oil leakage off the Santa Barbara

shore or

the pollution of the English and French beaches by Torrey Canyon are

likely to

increase rather than decrease in the future (Risebrough, 1969). The yearly production

of solid waste in the United States

alone amounts to 3.65 billion tons! This includes, for example, food

(garbage),

dirt (rubbish), paper, tin cans, plastic containers, abandoned cars and

trucks,

demolished concrete, paints, industrial scrap metals and chemicals,

asbestos

processing waste, blast furnace and smelting operation wastes, coal

culms banks,

and animal wastes produced in concentrated operations near urban areas

(Eliassen, 1969). If we try to eliminate

these 3.65 billion tons of

garbage, rubbish, and waste through our technology we will create

additional

problems. For example, technologically speaking, our sewage treatment

has

indeed advanced far enough to convert the noxious organic human waste

into

innocuous inorganic materials that could be disposed of in rivers and

lakes.

But then the addition to the water of excessive inorganic products,

which are

algal nutrients, results in algal overgrowth destroying in turn the

self-purifying

capability of the aquatic ecosystem (Commoner, 1969). This is what

happened to

such a massive ecosystem as Lake Erie where the harvest of pike fell

from some

seven million pounds in 1956 to 200 in 1963. Suppose the some six

billion

human beings who are expected to occupy the surface of this earth by

the year

2000 reached the garbage producing capacity of the United States'

present

population. In that year alone the world would produce some 127.75

billion tons

of garbage. That amounts to 250 tons per square kilometer of the

surface of the

earth-land and sea included. That would be a lot of garbage for a year.

This, of course, is a human calculation of what man defines as waste

and

"dirty." Looking at it from the point of view of nature, we can see

how man has artificially complicated his life. Of the 3.65 billion tons

yearly

waste product of the United States, one single item, constituting over

half of it

(58 per cent) is agricultural waste, including mainly animal waste (43

per

cent), notably produced in concentrated feedlots near urban areas

(Eliassen,

1969). While man juggles with the problem of disposing of it, nature is

deprived of this beneficial organic material which is the source of,

nitrates

in soil and water, and the supplier of nitrogen to plants, and the

animals that

feed on them. Cattle which were originally grazing in the Midwest

pastures and

contributed to the natural recycling of the soil were moved to the

feedlots

near urban areas. The land was then used for intensive grain production

with

massive use of inorganic fertilizers which, due to their high quantity

and

nonabsorption by the soil, ended up in streams and lakes, increased

algal

growth, and created water pollution. In cases where the polluted river

water is

used as a source of water supply, this creates the danger of infantile

diseases

(Commoner, 1969). In short, man's

technology,

after having damaged nature, is using it as a medium to turn against

its own

master. Man is no longer doing his share and in turn drawing his share

from the

ecosystem, but disrupting the recycling process of the whole nature and

thereby

threatening his very survival-the "ecological backlash."

There seem to be two dimensions to the

problem. One, that there are natural limitations on man's use of his

technological possibilities, and two, that there is not going to be

enough room

and food for the increase in population, mainly in the underdeveloped

parts of

the world. The two aspects of the problem were summed up in the

following

passages of Dr. Sterling Bunnell's paper presented to the conference. For example, if we

attempt to

postpone world famine by a cram program of feed production by any and

all

expedient applications of modern agricultural technology (especially

synthetic

fertilizers and persistent pesticides) we are apt, as Paul Ehrlich has

wisely

warned, to wreck the biosphere with chemical pollution; if we hope to

easily

replace fossil fuel power with nuclear power we exchange the problems

of C02

and hydrocarbon pollution for pollution by the equally dangerous and

more

insidious biologically active radioisotopes. If we try to extricate

ourselves

by conversion from fission to fusion power we may raise the tritium

concentration

of the world's water to a level fatal to our species. The critical

mutation

lead (if you are unfamiliar with this concept, consider it evidence of

the

inadequacy of your education to meet the requirements of survival) is

uncertain

before it is reached and there will be irresistible economic pressures

to

exceed any arbitrary limit in an overpopulating world hungry for power.

Thus it

seems that the problems of food production, power demands,

industrialization,

and waste disposal are not soluble in isolation, but only in

conjunction with

stabilizing population at levels which allow us to stay within the

limits of

environmental tolerance. A "breakthrough" on one problem (e.g.

greatly increased food supply as by development of synthetic

carbohydrates)

could finish us off by allowing population increase to intensify other

problems

(e.g. pollution, oxygen balance, thermal balance, etc.). B. The Ethical As I drove to the

airport under the hazy smoggy sky of

San Francisco I had a lot of compassion for those crossing my way. I

was

looking into the other cars, seeing people living in the smog of the

Bay Area

and pondering the problems that were facing mankind.

As I flew out of San

Francisco and over the vastness of

the United States, I started wondering whether the problem was there,

under the

little hub of pollution covering the Bay Area, indeed, little it was

compared

to what is left of this great country. True, 60 per cent of the U. S.

population lives in 1 per cent of its land. But could the some 77,000

persons

per square mile of Manhattan Island not go and live away from the smog?

After

all, the population density of the United States as a whole was only

50.5 per

square mile in 1960 (Heer, 1968). The answer to the

question was unfortunately negative.

They cannot. It is like sending the cattle in the feedlots back to the

Midwest

pastures. It is not profitable. Like

nature's cycles man creates for himself value systems which turn into a

vicious

circle. The more vicious they become, the harder it will be to break

from them.

Our industrial civilization has created its own system: that of

progress,

production, population, profit, and pollution. The system is not an

exclusivity

of the capitalistic free enterprise; the socialist and communist

regimes enjoy it

as well. It is that of the materialist approach to life. We pollute

Lake Erie,

the Soviets pollute Lake Baikal. One should produce, which is more

profitable

when there is concentration of manpower and market; and consequently,

one way

or another, one pollutes. As we saw earlier, even if we try to treat

the waste

we get the ecological backlash. Man, like Dr. Faust,

has sold his soul to the devil of

material progress. In the optimistic frenzy of materialist drive it was

believed that despite numbered bank accounts in Switzerland, despite

tax

loopholes, and despite helicopters going into flames, man could make so

much

out of mother earth that some day the leftovers of those who are good

at

competitive free enterprise or state capitalism, depending where they

are,

would finally bring to the rest of the lot those material gadgets which

would

qualify them as a "two car family," or whatever the criteria of

prosperity may be at the time. It was believed that the spoils and the

overflow

of abundance would finally reach ghettos and make the urban crisis

disappear,

and that despite colonial concessions, the developed could return

enough

charity to the developing that he would be able to satisfy his hunger. Had nature remained

passive and unlimited the question

would have been: was that the desirable end? We may hypothesize an

isolated

situation where a country like the United States (minus its racial

components

and out of the context of its poor neighbors) went for unlimited

material well-being

under free enterprise. Would it ever get there? Not unless it changed

its basic

terms of reference in the meantime, because the driving force of such a

system

is want. You have to keep running for it, and as long as you are

running you

haven't reached it, and if you stop running you will never get there!

At some

stage of material satiation such a society would have to stop and ask

the

question: so what? Fortunately or

unfortunately, depending on how you look

at it, that hypothetical isolated utopia does not exist. In the

hypothetical

isolation and absence of stimulants we may have imagined the young

indoctrinated to follow the path of the older generations, to cherish

the same

values, and to keep running a long time. In the context of the real

world many

come earlier to ask the question: so what? And understandably enough,

most of

them are from "two car families" and above! We are reaching the end

of the blind alley. Resources are not unlimited and discrepancies,

contradictions, deprivations, conflicts, and hypocrisies are immense. Above all, our ethics

and values are questionable. We are

told to tell the truth (because the child who tells the truth is better

controllable), and yet we may find in the behavior of our own parents

that

honesty does not always pay in the way of making a profit! We are

taught

rectitude but may find the very ones who preach it to be unctuous. We

are

taught to love our neighbor and see how that love of neighbor has

become a

material artifact of fund-collecting, while hates and jealousies are

what

make the competitive world go. We are told that sex

is dirty and that we should get

married and raise a family (because that is still the best way of

creating

responsible citizens). But then we look around us and see our parents'

sexual

hang-ups, the near-to-pathologic sex commerce, unhappy unions, and

lack of communication between parents and children, and we wonder

whether the

old institution corresponds to the new realities. The surface is being

polished; the dirt is creeping in.

The ethical structure of our society is not only hypocritical, it has

become,

in its artificiality, masturbative and prophylactic! Not only is love

dirty,

but also the body should not smell, the genital organs are a shame. We

are

denying nature its empire. The same way we take away the animal waste

of the

cattle, which nature appreciates, from the prairies of the Midwest and

make

them "dirt" in human terminology in the feedlots, the same way we are

killing our sensual side and inhibiting our energies for the sake of

aggressive

profit-making! The use of four letter words by the younger generation

is

not only a revolt against the established hypocrisy; it is a means of

shedding

away the prophylactic culture. They are making acquaintance with their

glands,

bowels, and genital organs and their uninhibited functions.

Incidentally, this

revival of communion with the sensual side of man may help racial

understanding

between the young blacks and whites in the United States, as the latter

start

developing and appreciating the sensual side which the former have

always

enjoyed. The problem is that

the issues are so basic, the

solutions so contrary to the established values, and the time for

conversion so

short that humanity finds itself in the pre-Revolutionary psychological

conditions. Some pound the table of argument to the point of revolt;

the others

stick their heads in the sand for solution. Those who revolt do so

against the established values,

but theirs is not necessarily a solution unless they are prepared to go

all the

way to the logical conclusion of their act. A revolt is not a cure in

itself.

It is the fever and the bursting of the abscess. Thus, for example, the

hippies are returning to nature.

While their way of life is a reaction to the material and technological

civilization, one wonders whether in the context of the surrounding

technological society it can be a lasting culture and whether it can be

an

answer to the problem of population increase. It is likely that in the

absence

of a deep-rooted social and spiritual doctrine, second-generation

hippies who will not have the personal experience of their parents

about the

materialistic civilization will succumb to its glittering polish. That

is, if

we assume that the first generation itself will not. The hippie

experience has

yet to stand the test of time. Many attempts at communal life with

varying

levels of organization have been made in the past, from the Brook Farm

Institute to the Oneida Community, and they have not survived. But suppose a movement

for communal simple life and return

to nature could create enough of a deep-rooted doctrine which enabled

it

to perpetuate itself and propagate its message. It will only be serving

its

purpose of man's salvation if, as indicated earlier, it is prepared to

draw the

logical conclusion of its raison d'être,

i.e., total renunciation of its surrounding technological facilities.

No appeal

to technology and medicine for better nourishment and health, letting

nature

regulate their number by famine and disease. Even appendicitis, not to

speak of

epidemics, can kill a lot of people. Without such renunciation they are

solving

no problems. They are adding more. The Hutterites, following their

simple

communal existence have a 4.00 per cent birth rate, together with that

of Cocos-Keeling

Islands (4.2 per cent) the highest in the world (Eaton and Mayer, 1953;

Sheps,

1965; Smith, 1960). There are those on the

other hand who foresee the

solutions of man's problems through more of the same things. The more

fantastic

their forecasts are, the more they skip the phase of conversion and

delude

themselves in daydreaming. Thus, they say, the day will come when we

will live

in artificial satellites, extract metals from sea water and ordinary

rocks,

stabilize world population at about three times its present number, but

solve

food and health problems by radical transformation of human nutritive

habits

and universal hygienic inspections. Unfortunately, they don't tell us

how they

are going to get us there. (Ellul, 1964). Even Ehrlich, who is making

more

transitional proposals to solve the problems of pollution and

population (such

as addition of sterilants to staple food or the water supply to keep

the

population from procreation) does recognize that they are socially

unpalatable

and politically unrealistic! (Ehrlich, 1968). It

is precisely the social, economic, ethical, and

political stumbling

blocks which cause some to revolt against the establishment and others

to shut

their minds about conversion and dream about the next scene, utopia.

But they

offer no real solutions, and the more we beat around the bush the more

it

becomes obvious that the key to the problems must be found within the

ethical

and social contexts which are held as taboos. III

- PROGRESS, PEACE AND PLENITUDE

“For the great enemy

of the truth

is very often not the lie - deliberate,

contrived

and dishonest - but the myth

- persistent, persuasive and unrealistic.”[6] Redefined, in brief,

materially

speaking, the problem that faces man is that on the one hand he is

growing in

number and on the other hand he cannot provide for the mass of humanity

the

comfort, energy and food that it will want. If he technically tries he

will

face the ecological backlash, and even if he succeeds he will face the

spiritual question, "so what?" He has to limit himself in procreation

and he must limit the satisfaction of his material wants. The

proposition is

whether instead of materially restraining himself he will not be better

off if

he reviews the values on the basis of which he first started on the

course

towards increase in population and material wants, and to see whether

through

an intellectual and spiritual reëxamination of his basic values he can

change

his basic goals. The assumption is that

the desirable end is the happiness

of man. If man restrained himself in procreation and satisfaction of

his

material needs despite the existence of want in him toward these ends

he would

be unhappy. But if he came to realize and convince himself that these

are not

desirable goals to start with, then man would find himself in the happy

state

of rationally and voluntarily not wanting them and finding them

superficial and

irrelevant. I say "rationally and

voluntarily" in order to

distinguish between myth and indoctrination as against reality and

will. It is

in the latter context that we should look for the solution. A close

look at

some of our prevailing values will not only show their anachronistic

nature,

but will reveal that despite the resistance and hostility of the

bigots, a

trend towards their critical analysis and change has already started.

But the

pace is slow and the attitude limited to a group of elites who because

of other

social motivations do not always confess their inclinations. They play

the

bourgeois game and pay lip service to the religious, political, and

economic

establishments. The modern man should

realize that the social motivations

he has created for material satisfaction and bourgeois contentment have

not

only ceased to be sufficient for bringing happiness to man but are

becoming

detrimental to him. A. Happiness and Knowledge as Values When we look at some

of the values which make the Western

civilization go, such as hard work, individual enterprise, and material

progress, we get the feeling that our materialistic approach to life

somehow

missed the Jeffersonian boat. Jefferson had a point when he paraphrased

Locke

and turned "life, liberty, and property" into "life, liberty,

and the pursuit of happiness." 1.

Less

Temptation Is there no better way

of being happy than to procure

more wealth and do better than others? Does competition really make man

happy?

Does it offer a means for satisfying wants or does it only provide the

social

incentive to produce more? Surely if progress and production as social

norms

could go on with no drawbacks, the artifact of competitive enterprise

could

make the individual a better tool for the perpetuation of those norms.

But if

they are going to end up in the pollution of man's body, soul, and

environment

is it not time to bring a halt to that frenzy? For the consumer to

start wanting less, the producer

should want less. But who is the producer and who is the consumer? In

1952 only

about 6.5 million, or 4 per cent of the Americans were shareholders, by

the end

of 1968 some 26.5 million, or 13 per cent of them held shares.[7] Thus the logical

extension of wanting less is really

wanting less profit and what has become its ultimate manifestation,

money. But

capitalists are many. In order to reason with business we have to deal

with its

shareholders. It is the average shareholder, consumer, and producer, in

other

words, the public at large whom we have to reach and convince that

wanting less

is for his own good. Of course under the

present conditions of competitive

free enterprise with little regulatory system of distribution we are

not well

justified to bring this messianic word to the some 26 million people in

the

United States who are below the poverty line.[8] The

sermon should not be misused as yet another gimmick to

make the poor

render to Caesar what belongs to Caesar. The poor's want is a need, not

a

frivolous desire. True, it is difficult to draw a hard and fast line

between

what is needed and what is a superficial desire. But somewhere between

the

adequate amount of protein for healthy survival, or reasonable shelter

on the one

hand, and increased temptation to overeat apples by the addition of

artificial

coloring, or insertion of a semi-nude in a new super car (going 160 mph

for highways mostly having limits of 70 mph) to make it irresistible on

the

other hand, a fairly clear line can be drawn. We must make a new

evaluation of the GNP of junk based on

waste economy and conditioning of the consumer through publicity. Is

the United

States' GNP really comparable to that of Sweden or Germany when they

produce a

car to last, while the American producer makes a car to go to the

junkyard?

When most of the private houses in the United States are built to be

torn down

by the time their mortgages are paid, that is, if they have not been

knocked

down by a tornado or a hurricane? Not only is the production ephemeral,

the

consumer has been indoctrinated to want it that way. The irony of it all is

that the indoctrination of the

whole population with the lure of materialistic well-being and

profit-making

has made the task of disentanglement a much more colossal job. Were we

faced

with a few capitalists, presumably well-educated and materially

satiated,

we would probably have less trouble demonstrating to them the imminent

dangers

of over-production and pollution resulting from their appetite for

profit. Indeed, some come by themselves to realize that there is more

to a

man's life than the satisfaction of amassing wealth. Extremes such as

David

Owen in early 19th century England are few, but Kennedys, Rockefellers,

Carnegies, or Fords have social ambitions beyond material profit. Of

course,

this tendency is also a shortcut direct to power. But the system has

become the peoples' golden calf. The

middle-class shareholder buys shares to maximize his profit, not for

doing charity. He does that elsewhere at his church or United

Fund-adding

to his prestige and status. He has the mentality of the common man with

the

"common" standards of our bourgeois civilization. He wants to be

successful. We have to get to him

and tell him that he has fallen

into a vicious circle. That where he is running to is nowhere and by

accelerating he is only complicating life for himself and humanity.

That the

faster he runs the less he sees and appreciates what passes him by. It

is an

absurd thing to do, considering the fact that he is running nowhere.

Time is

short; we cannot wait for him to come to himself. The younger

generation is

awakening. But all those over thirty whom they don't trust are going to

be

around for a long time and will continue on the track set before them

and in

the process corrupt the young. In short a crash adult

education program to disentangle

the people from obsolete myths and values is urgently needed. Granted,

man has

not been very successful in the past in bringing aesthetic,

philosophic, and

spiritual appreciation and taste to the level of the commons. But has

that not

been a question of lack of means to bring adequate education to all?

Can the

affluent society not make a try at it? There have been times of

Buddhist, Judeo-Christian,

and Islamic piety when societies lived in relative harmony with

themselves and

nature. Should man be made reasonable only by the fear of God and

heaven? Is

there not a possibility that man may rationally limit the use of his

material

wealth with moderation, distribute it better, and make little waste?

Can he not

come to use his intellectual and spiritual capacities and his reason to

the

maximum? The hope for some

success in this direction exists in the

fact that as things go, the growing number of those who live in the

congested

smoggy concrete jungles may come to see a point in it. It will be

easier to

convince a New Yorker than a rural villager that he should restrain

himself in

the use of his car and go for a public transportation system which will

be

providing facilities for all and therefore will be better distributive,

more

efficient, and less wasteful. For this we will have

to reverse the trend of present-day

salesmanship publicity. Indeed we may have to fight it. Man should not

be

enticed to long for bigger, faster, and flashier cars with four-barrel

exhaust pipes. He should be made conscious that every time he pushes on

the

pedal and creates more carbon monoxide, he is committing an unethical

act-if

not a crime-considering the statistics that show the increase of lung

and

skin diseases due to smog. If air and water are common property, it

does not

mean that man is at liberty to throw his garbage into them. Every time

he does

so, whether as an individual or as a manufacturer, he is transgressing

the

rights of the others who breathe, drink, and use these common

properties. The

driver should be encouraged to hike whenever he can. It will be good

for both

his own well-being and his appreciation of his social and natural

environment. He should be made to use public transportation which, if

he did,

would permit its improvement and bring him more in contact with his

fellow men. Along the same lines

people should be taught that it is

unethical to induce a man to consume more than necessary and to buy

what he

does not need. That it is unethical to make goods of low quality, which

could

be made better, and longer-lasting. That it is equally unethical to

replace utilities before they cease to be useful and thus create more

junk.

That products should not keep changing their form and fashion, creating

more

temptations. That even if it may be economically not profitable,

wastes such as scrap iron, paper, glass, etc., should

be used to avoid pollution. Many European countries with limited

resources have

been doing that. I do realize that all

this means less consumption, less

production, less profit, and less employment. Reduction in the first

three

items is the desired end. As for the last item, the assumption is that

a total

examination of man's goals and values will permit him to realize that

in a less

competitive and more reasonable society there are better possibilities

of

social justice and redistribution, permitting all to do their share and

satisfy

their needs. I do realize the difficulty of bringing about such a

drastic change

in a civilization so totally deluded in materialistic interests and

profit-making

that it can hardly find judges for its high court who have not indulged

in

profitable transactions (viz. Fortas and Haynsworth) and its

government

has to lift its law on harmful products (cyclamates) and stop pursuing

its

action against fraudulent banking (numbered bank accounts) under

pressures from

appropriate lobbies. In the present

psychological state of modern man it is in

a way easier to make him take sterilants in his water and staple food

as

Ehrlich suggests than to do away with his profit (Ehrlich, 1968).

Sterilants

affect his body which is already full of stimulants, tranquilizers

lead, DDT,

radiation, etc. What is being suggested here is to lighten his pocket.

That

hurts. But like the constipated child who has to take his Milk of

Magnesia

sooner or later, the modern man will have to take the laxative, better

sooner

than later. Where is he going to

start? Obviously what it all boils

down to is a massive eye-opening program. The only problem is that it

will need the help of those whom it is eventually going to demystify.

But the

issue is not as hopeless as it appears because of the seriousness and

reality

of the hazards involved in not undertaking it. The conservationist

movements may start a campaign

similar to the one undertaken by the Cancer Society against the

cigarette

industry. Congress ended up passing laws against the cigarette industry

and

curtailing its advertisement. Are the exhaust pipes and what is

connected to

them or the artificial food coloring not equally noxious for human

organisms?

In fact, there are more laws than one thinks against abuses by the

industry.

But very often they are dead letters, not implemented or not properly

enforced. The campaign should in

the first place, be directed

against commercial advertisement and toward intellectual education of

the

masses. It will eventually make the politician aware of the problem and

make

him adhere to it when he sees the possibility of support from an

awakened

public. Ideally, legislative action should ban publicity and

advertisement for

commercial purposes, and create incentive for redirecting funds thus

liberated

to foundations which would make them available to mass media for the

development of educational and entertainment programs under the

supervision of

scientific, cultural, and educational institutions. Depending on the

response from business and industry,

laws can be made more or less categorical. There are, no doubt,

obstacles in

the way of such a project. Only a few years ago the FCC faced the

strong

opposition of the House Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee for

wanting

to impose on the industry its own standards for advertisement on the TV

and the

radio. But what is suggested here is really nothing spectacular. The TV

and

radio programs of many countries in Europe did not have commercials on

them

until recently. Now they are trying the American way. The trend could

have been

in the other direction. Of course, in many of the European countries

the TV and

the radio stations are under governmental control. In the U. S. they

are in the

hands of business. Can we not liberate them for a while and see what

cultural

institutions and higher learning can do to them? 2. More Learning The scientists should

be recruited to co-operate

actively in such a campaign. They should also re-evaluate their role

and

responsibilities within the society. They should be reminded that in

the

earlier days, material application of research was only an incidental

part of

the scientific drive. The scientist was learning for the sake of

learning,

although some became so involved in their drive for knowledge that they

sometimes overlooked the side effects and undesirable consequences of

their

research and discoveries. As the tools of scientific research became

more

expensive with progress, and as those seeking profit and power found

out about

the practical uses of science for their own ends, business and

government

flaunted the facilities they could offer to the scientist and ended up

buying

his services. The regrets of J. R. Oppenheimer for having unleashed the

nuclear

power are well known. In the process, the

gap between different branches of

science widened. The industrialist in search of profit would

immediately opt

for the use of technology in the automation of his enterprise or the

manufacture of a new product invented by the physicist or the chemist.

The

works of a political scientist or psychologist pointing to the adverse

social

effects of the new technology could find no immediate hot buyers. Those

interested in the social problems are either social scientists without

means

for actions, or philanthropists with limited means. The government

agencies, in

state controlled economies, often behave like the capitalist

industrialist,

and, in the free enterprise societies, lag behind in dealing with

social

problems and cope with them only when they become acute or when they

help in

reelections. The example of water and air pollution in the United

States and

other industrialized countries is significant. The scientists are

today in a position to act. They

should first of all become conscious of their solidarity in their

ultimate

goal: that of simple and yet immense happiness in learning. They should

develop

further interdisciplinary consultative mechanisms among the physical,

natural,

and social sciences enabling them to have a more global approach to the

effects

and consequences of their scientific advancements. Those who are

concerned

about the adverse effects of technology and environmental deterioration

can

help in the establishment of this dialogue between the scientists free

from

governmental and business patronage. Ways and means should be examined

for the

control of the indiscriminate use and abuse of scientific discoveries

by

business and government. They should assert the rights of the

scientists to

control the application of their knowledge. Finally, scientists should

play a

capital role in awakening public interest in the appreciation of

knowledge and

the joys of learning as an end in itself. Imagine investing all

the money business is spending in

publicity for educational purposes. Not only would it stop the creation

of new

wants, new brands, and new pollutants, but also it would create such a

variety

of means of learning that knowledge could be made attractive to the

most

unmotivated and unsophisticated individual. Man does want to

learn. Unfortunately in our materialist

and bourgeois civilization the common man is oriented to learn for

material

goals, not to learn for learning's own sake. His drive for learning is

then

satisfied by superficialities and gossip; and thus limited and ptone to

exploitation for political and economic purposes. Imagine the day when

men can spend their time learning

creative art, music, painting and dancing. When they can study

oceanography and

astronomy, history and anthropology, savor their knowledge of flowers

and

animals, plains and mountains. When the man you meet will tell you

about the

interpretation of the prehistoric paintings of Altamira and you can

tell him

about the latest pictures of animal life in the deep seas. When the man

you

meet will no longer limit his early questions to whether you have a

family and

children and how much money you make: Clearly he is the product of our

materialistic civilization. These are the same questions the banker

asks you in

order to give you credit. He does not care whether you are an honest

man or

not, and, under the circumstances, he is right. If you are a product of

this

civilization, the best way of checking on your honesty and

responsibility is to

see whether you have surrounded yourself with the commodities, wife,

children

and other belongings, which make you materially responsible and

respectable.

The Wall Street offices were surprised recently to find their hippie

messengers

more reliable than their usual bourgeois employees. The time has come for

industrialized society to realize

that man is not the tool of technology, but the latter at the service

of man.

Man and nature are the ends. With our means for material satisfaction,

let us

try the contemplative happiness dear to Aristotle and Jefferson. B. The End of the Bourgeois Family! But so far what we

have discussed has been aimed at

reducing the material wants of man and thus curtailing consumption,

production,

and therefore the ill of pollution. Whether we have at the same time

advanced

any solution to the problem of population is not apparent. The modern

educated

man may prefer his sausages without artificial coloring and delight in

the

study and admiration of ancient Egyptian obelisks. Why should he stop

making

children? For that we have to revert back to our original proposition

for the

critical reexamination of our values and see whether they correspond to

our

modern realities. The educational programs should not only aim at the

appeasement of the material wants, but also question the social myths

and

values surrounding them.

1. Procreation "It is the nature of

every

man to love life and hate death, to think of his

relatives and

look after his wife and children. Only when a man is

moved by

higher principles is this not so" Ssu-ma

Ch'ien. The higher animal that

man is,

according to his findings, controls his behavior more by socialization

than by

instincts. Thus he should be able to justify his acts and institutions

socially. Should he want children? Ehrlich, by adding sterilants to

staple food

and water supply, wants to make of children a scarce commodity

(Ehrlich, 1968).

I suggest making man aware, through education, that the reasons for

which he

wanted children no longer exist and therefore he should no longer

desire

begetting them and be happy not having them. He should realize that

today

children are only a heavy social responsibility. Why did man want

children in the first place?[9] In

the social context, the child corresponded to an

economic tool in

rural areas and early industrial societies. It was also considered as a

support

for old age. In developed countries, these roles of children are

replaced and

can be further replaced by social phenomena such as social security and

mobile

manpower. A survey in Japan shows that while in 1950 more than 55 per

cent of

those interviewed answered definitely yes to the question as to whether

they

expected to be supported by their children in their old age, only 27

per cent

gave an affirmative answer in 1961 (Freeman, 1968). Incidentally, Japan

is one

of the nations which have had a descending population growth rate. In the days when man

had little amusement and his

entertainment was not diversified, one may well imagine the source of

joy the

children were. Girls who played with dolls made of cloth rejoiced to

change

diapers of real babies. Today their early dolls speak, wet, and walk.

Nothing

is left for them to imagine. And as a young married couple was saying,

children

would interfere with their social activities, travel, and television

watching!

If only we could make the contents of these events more meaningful. Man also saw in

children his own continuation after

death. But in our fast-moving world, even before their teens children

no

longer identify with the world their parents have lived in and parents

cannot

recognize their own image in their progenitor. And then before maturity

is

reached, children fly away to become often far away acquaintances in

the long

life which normally awaits aging parents these days.

Then what is left of

the drive for making children? Well,

people do not know for sure, but feel they should make them. It is

above all

the indoctrination received from the parents, which may have been

justified in

the past when factors reviewed above were still valid, but are no

longer.

People should be made to understand that it is most irresponsible to

inculcate

the younger generations with the drive to get involved in marriage and

procreation. No doubt there is much

pleasure in holding a child in the

arms, caressing its fluffy hands, looking into its big innocent eyes,

seeing it

smile and mimic. But one should be made aware of all the accompanying

troubles

and responsibilities. Just because people can engage in sexual

intercourse does

not make them good parents and educators. They may pass on to new

generations

the shortcomings of their own character and personality. Much of the

generation

gap the parents are complaining about is precisely due to the

inefficient,

permissive, gnomic, and double standard education they have provided

for their

children. On the birth of a

child, then, the parents should be

presented with censure and condolences. Congratulations should go to

them if on

his 20th birthday their child is well-educated and the parents have

managed to keep the lines of communication and understanding open with

him! Should, however,

couples beget children while recognizing

their incapacity to give them proper education and care, they should

see to it

that adequate arrangements are made (which they could make on a

communal basis

near their home base) for the competent men and women with pedagogic

inclinations, know-how, and feelings to be entrusted with the care of

the

children at an early age. This again will not be a spectacular

innovation in

our proposed campaign but simply will aim at making the masses

conscious of

what is in reality taking place but is obscured and slowed by

deep-rooted

obsolete and hypocritical attitudes. Parents equate

happiness and success with getting married

and, having children, or men or women want to have a child-as if a

child

were a toy; and fathers and mothers declare that they want to take care

of

their children themselves-as if the children were their exclusive

property; forgetting that society lives with their children longer than

they

do![10] The politician running

for election who displays his wife

and numerous children on the podium as a factor of persuasion is a

doubtful

candidate. If his children are well brought up he must be regarded as a

selfish

man not fit for public office, even if he had a good record of public

achievements, because one should wonder how much better he would have

done for

the people had he not fiddled with his family! If his children are well

brought

up because he had entrusted their care to competent educators, he has

no merit.

And finally if his children are not well brought up he is obviously an

irresponsible person.[11] 2. Matrimony Then what of marriage

and family, when the incentive of

making children is reduced? Traditionally, the family has been the

basic social

unit for the division of labor. The man used to gain the livelihood

outside

while the wife had a full-time job making the fire, cooking, washing,

sweeping, mending, and looking after the children; and of course,

satisfying

her husband's sexual appetite-sometimes enjoying it herself too. In

most

societies, due to the inferior social status of the women this position

was

equated to a long-term exclusive prostitution in exchange for

protection and

upkeep. All these premises of

the institution of marriage have

become irrelevant. The electrical appliances do better and much quicker

cooking, washing, and sweeping than the ablest housewife doing them by

hand.

Besides, the younger generation of females is not very good at mending

and

makes a point of it, too! They have gained social equality and do their

share

of economic division of labor outside the house. On the other hand they

come

more and more to emphasize that if socially equal they are

physiologically

different - "Vive la petite différence" said Madame

Paul-Boncour.

So they ask for their share of orgasms, too, which tends to make sexual

relationships not so exclusive after all. Newspapers recently reported

liberalization of laws to this effect in Sweden. Then why marriage, you

may ask. Indeed why? For

companionship? But does companionship need to be sealed by a contract

and

consecrated by the Lohengrin nuptial march! Can people, or rather,

should people,

not simply live together? They will thus daily reaffirm "to love and to

cherish" and the hypocritical and ridiculous repetition of "till

death do us part" will be avoided for re-wedding divorcees! Marriage

should not be the business contract it is. It should in essence

sanctify a

dimension of love which does not correspond to the reality of the

institution

we have made of it for the satisfaction of our material purposes. In a diversified

society, where males and females who are

attracted to each other may be of different environments, of different

educational, ethnic, and religious backgrounds, and may have

occupational

specializations pulling them apart, would it not be wiser to leave

companionship to the free laws of attraction and personal

compatibility? You

may be surprised; we may well have many more harmonious, long-lasting

unions. For the close of the

1960s, the AP News feature writer,

Sid Moody, reported Amitae Etzioni's concern about the danger that the

new

generation of college girls and boys after living together, avoiding

thus the

boys' living in fraternities and going to whore houses - which he found

wholesome and approved of - may end up not wanting to found families.

This, he said is dangerous because family and authority are the basic

factors

for social order. But doesn't he see that it is precisely the kind of

social

order we can no longer afford?! The social order which produces more,

among

other things, people, pollution, and unsatisfied individuals, and whose

authority is in the hands of the producing machine which imposes itself

on the

ignorant masses softened to submit because they have a family to feed

and a

respectable status to maintain, and because they run and salivate for

what the

social order has conditioned them to run and salivate for. Should the future

social order not rely instead on

responsible and educated individuals who have cultivated the wisdom of

limited

wants, and boundless contemplative, spiritual, and aesthetic joys?

Anarchy has

two meanings; one is the more popular understanding of it as a state of

chaos,

the other the highest degree of individual's consciousness of his

social role

and responsibility to an extent which makes external control and

authority

meaningless. Has the time not come to try it? The time is too short to

go for

anything less than man's ultimate dreams. This seems the only realistic

way! C. Nation Among Nations But who is going to

try it? The western affluent society?

Then what will become of the 800 million Chinese, the 400 million

Indians, and

those millions who, under the banner of Marxism, have set the goal of

surpassing the United States in material production. So far I have tried, I

hope with some success, to combat

hypocritical values and situations. At this stage stepping on a few

more toes

will make no difference. So let us examine some of the international

dimensions

of the problem. A program of the

nature proposed above will aim at a more

educated public, a more distributive economy, and enlightened human

beings who

will be less aggressive as a nation on the international plane. The

United

States or for that matter any developed country will not be able to

envisage

such a situation unless it has sufficient grounds to believe that this

policy

is the general trend of all developed countries. There must also be

reasonable hopes that the developing

countries have overcome their inferiority complex of wanting to get in

the same

critical situation in which the developed countries find themselves.

They

should be prepared to modify their national Weltanschauung and

to adopt

a policy of growth which will not create in their population the frenzy

for

excessive material goals, but will blend with it contemplative,

aesthetic, and

philosophic dimensions. This proposition may be easier for the Eastern

people

than for the West because of already existing deep-rooted traditional

premises. Like the western traditions, however, theirs should be purged

of

superstitions and obsolete myths. It is unfortunate that in the East,

too,

spiritual values are dying in the face of glittering material

incentives. As one follows

meetings, committees, and conferences on

pollution and population, one distinguishes between the two opposing

concerns

of the haves and the have-nots. Even when a conference is a national

gathering,

the particular concern of the category involved is discernible. The

haves are

really afraid of population. "They are going to come and get us," one

seems to read in the back of their minds: the Visigoths plundering

Rome, the

hordes of Attila and Chengis Khan galloping across the European plains,

the

Turks charging the walls of Constantinople. The have-nots are

thirsty for material comfort and

power. They seem to think: "They don't want us to get there," and

their thought invokes the specter of colonial days. A close look at the

U. N.

debates on the subject will provide revealing samples of the hidden

motives.

They cut across ideological frontiers. The Soviets want to get

"there" and at the same time are afraid that "they" will

come and get them. The madness of

competitive enterprise has become an

international ill. How can those fighting the construction of SST not

realize

that the United States cannot renounce such means of transportation

when others

have it? That is the only way to stay ahead, to remain vigilant and

defend the

national interests. The others think the same way, both the haves and

the have-nots,

each holding to their respective weapons and, in the process,

committing

suicide. The technologically advanced are going at it full speed for

total

pollution. The underdeveloped, especially the competitive ones, are

holding to

their ultimate weapon: the masses, to starvation (Pearson, 1969). According to the

latest information, the Soviets are

dotting their Chinese frontier with missiles, and, last August,

nominated

General Vladimir-Tolubko, missile expert, to head the Far Eastern

Military district, while the Chinese Militia, estimated at some 200

million,

are digging individual fall-out shelters on the other side of the

border

(L'Express, 1969). The eventuality of

such a confrontation, which will drag the whole of humanity into

disaster, may

seem absurd. But has man not committed more absurdities than reasonable

deeds?

Only this time we are more numerous and we have more destructive toys

at our

disposal. Then should the

developed countries not feed the hungry

before "dematerialization?" Had there been a possibility of success,

it could have been considered. True, if the United States cultivated

all its

arable lands to the maximum, she would be able to fill in the world

food

shortage in the 1970s and even have a surplus. That is to say, by

extensive use

of energy, pesticides, and fertilizers, turning her lands into

vulnerable

reservoirs of chemicals and its waters into algae soup! Yet at the

present rate

of world population growth, the battle will be lost sometime around

1980.

Besides its not being realistic, this kind of concessional help risks

damage to

the aided country's agricultural development by killing local incentive

(Pearson, 1969). Let us, then, face the

fact that the world, divided as it

is between the haves and the have-nots and along ideological lines,

with

its limited food producing capacity and its growing population, has a

problem.

A serious problem of survival. As things stand the problems can be

solved only

at the price of great sufferings, sacrifices and compromises.

Unfortunately, at

the international level, the egocentric and ethnocentric tendencies of

man are

more accentuated and the means available for curing them inadequate. It

is

easier in the national context to make a campaign to persuade those who

are

struggling in the smog against social injustice and anachronic social

structures near to their skin to take a second look at their values and

institutions. It is more difficult to make the fat, developed nation to

feel

what chronic hunger feels like, or to make a deprived nation realize

the

emptiness of material prosperity in a dog-eat-dog smoggy world. It

has to get to their skin before they feel it, and by then it will be

too late. At the international

level, means of persuasion are

limited and the anachronistic concept of sovereignty supreme. Under

such

circumstances, achieving the strict minimum for man's survival will be

the

greatest feat of mankind in the coming decades. Sad as it is, it will

be

proving immense naiveté to recommend that nations turn their tanks into

tractors. The recent Pearson

report makes a whole range of

recommendations for the minimum degree of co-operation needed in way of

development (Pearson, 1969). Let us hope that by the time of the U. N.

Conference on Man and His Environment in Stockholm in 1972, the

developed

donors of technical assistance will have pledged themselves and started

implementing the recommendations of the Pearson Commission to bring

their

resource transfers to developing countries to a minimum of one per

cent, and

their official development assistance to a level for the net

disbursements of

0.70 per cent of their GNP by 1975. Let us also hope that

by 1972, the developing countries

will be in a position to take the responsibilities that go along with

sovereignty and independence and will pledge themselves not to require

foreign

concessional food aids by 1975, except in cases of natural

catastrophes. Such a

proposition seems to be in line with the actual trend in many

developing

countries and could be achieved by all if they directed their national

efforts

to the rational use of their agricultural resources. Hoping that it

will be

brought about more by better management and improved agricultural

techniques,

such as extensive farming and choice of superior seeds, than by

excessive use

of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. A policy of this

nature will also have to bring about the

purge mentioned earlier of the superstitions and obsolete traditional

myths and

practices which constitute social and economic stumbling blocks

particular to

those societies. Here again the role of a mass national educational

campaign

becomes obvious. We have to recognize

however that a special effort is

needed on the part of the United States to do her share, even in this

limited

international program. In 1968, the U. S. official development

assistance

constituted only 0.38 per cent of the GNP (Pearson, 1969 - Table 7-3).

Further, a substantial amount of U. S. aid to developing countries has

been in

food aid (31 per cent of the U. S. aid commitments in 1967). This is

due to the

fact that the U. S. food aid to developing countries ever since 1954

has at the

same time served as a self-help to regulate the national food

production

surplus (another materialistic dimension of this culture). So if by 1975 the

developing countries are to stop asking

for concessional food aid, and if the United States is to reach the

minimum

target of resource transfer and official development assistance of 1

and 0.70

per cent of her GNP respectively, the campaigners against pollution

should

include foreign aid in their mass education program. They should also take

into consideration the broader

international problems briefly referred to earlier and realize that,

for

example, an international conference such as the one planned for 1972

in

Stockholm on pollution and population will not be a realistic

undertaking if it

does not have the 800 million Chinese represented, or does not link its

topic

directly to the questions of disarmament and development. IV

– EPILOGUE

It may sound a curious

proposition to the conservationist to be asked to look into our

material,

ethical, social, and international values and problems in order to save

the

trees, flowers, and animals he cherishes. But that is where I think he

should

start. And he had better start quickly, because the alternatives will

not, I am

afraid, be to his liking. At the one extreme is

the very

serious threat, considering the idiocy of mankind, of a nuclear war.

Its

protagonists should, by the way, be made aware that it would not be a

short

one. With the miseries, hates and deprived masses that it will leave

behind,

man will get involved in a long and savage war degrading him to the

stone ages

on top of the ashes and blown around by the radiated air. At the other extreme

is the

technologically perfect world which is no longer in the realm of

science

fiction but a reality awaiting us around the year 2000, that is, if we

ever get

there. If we did, we would no longer be we! After the Beckwith/Shapiro

recent

scientific achievement at Harvard of isolating the single gene, it will

soon be

possible for man to manipulate genes to produce the ideal man." Or

shall we say the ideal "being"? Man's ideal being. And that creature

will not look like man at all. We are already planning ahead. The

prototype is

not yet ready but some ideas are crystallizing.

For example, according

to Nobel

Prize winner physicist, Charles H. Townes, man should be smaller and

lighter,

and according to Dr. D. Recaldin of London University, he should have

chlorophyll under his skin in order to perform photosynthesis like

plants. He

will be green?! Then why not have wings too? And why should we see only

in

front of us? Why not have compound eyes? We will nearly succeed being

bees,

green bees! Maybe this is the way bees started on the road to beehood! We must also consider the fact that we will

also be able to grow children in vitro,

and not just any child. We will use congealed ovum and sperm of

selected men

and women who have passed away and whose superiority we can objectively

determine on the basis of their deeds (Ellul, 1964; Rosenfeld, 1969).

Man will

feed on synthetic food and acquire knowledge through electronic

messages

directly transmitted to his nervous system. Obviously man's social

problems

will be solved by proper arrangement of the genes and the electronic

messages

so that everybody will be performing his social role satisfactorily and

with

satisfaction. These are not phrases taken from Huxley's Brave

New World. Besides, Huxley's dream is rather simplistic

compared to what science has in reserve for us. Charles H. Townes and

Herman

Muller are Nobel Prize winners! Jules Verne and H. G. Wells predicted

man's adventure

in the space. We did it. How are we not to get to the Brave New World? “God is

dead! God remains dead! And we killed him!. . . What lustrums, what

sacred

games shall we have to devise? Is not the magnitude of this deed too

great for

us? Shall we not ourselves have to become Gods, merely to seem worthy

of it?

There never was a greater event, - and on account of it, all who are

born

after us belong to a higher history than any history hitherto!” - Here

the madman was silent and looked again at his hearers; they also were

silent

and looked at him in surprise. At last he threw his lantern on the

ground, so

that it broke in pieces and was extinguished. “I come too early,” he

then said;

“I am not yet at the right time. This prodigious event is still on its

way, and

is traveling - it has not yet reached men's ears. Lightening and

thunder

need time, the light of the stars needs time, deeds need time, even

after they

are done, to be seen and heard. This deed is as yet further from them

than the

furthest star - and yet they have done it!” (Nietzche,

1882) BIBLIOGRAPHY